Editors’ Selects: January 2026

Tom Burr: Journal Works

The Upstairs at Bortolami | 39 Walker St, New York

January 9 – February 28, 2026

The mural is the collage’s sleeker, older sibling. That is, according to Ellsworth Kelly, who once urged in a 1950 letter to John Cage that his collages are merely precursors to what is eventually placed directly onto the wall: “my collages are only ideas for things much larger — things to cover walls.”[1]

Alternatively, Tom Burr stages a family reunion between the two forms in his Journal series, one that upholds the collage rather than subjugating it to its larger counterpart. The first exhibition solely dedicated to the series is currently on view at The Upstairs at Bortolami, where fifteen of its twenty-nine constituents are arrayed. Journal Works advances Burr’s ongoing creation of wood-mounted collections of material, which he dubs “bulletin boards,” a practice initiated in the late 1990s.

Each Journal work alludes to a panel from Kelly’s Sculpture for a Large Wall (1956–57), a 104-part anodized aluminum sculpture originally commissioned for Philadelphia’s Transportation Building Lobby yet jeopardized upon its abandonment (and now in MoMA’s collection). The relation between Sculpture for a Large Wall and Journal Works is mutualistic—and an intergenerational one, at that. Vignettes of Kelly’s structure in the form of metallurgical color blocks anchor the contents wielded by each “bulletin board,” while Burr’s contents elucidate covert spaces left by its predecessor.

The Journal works ooze queer methodologies. We catch glimpses of photographed icons, second-hand clothing articles, and library books—archival remnants of a different time. Their rectilinear, color-coordinated compilation and comprehensive materials lists give the illusion of precision. Nevertheless, as their objects are gathered for the keeping, they are simultaneously made precious in precarity. An Arthur Russell vinyl resides alongside an empty DVD case. Collaging is hardly just collecting for the sake of presenting; it concurrently posits obscurity. It’s an exercise of object permanence. Journal contents are chasmed, parts of a whole memorialized in their segmentation. Allen Ginsberg’s Howl exists in its entirety, but solely an excerpt is what we are allowed in this context.

Between its conceptual basis on Kelly’s site-specific mural and its intricate sculptural topographies, Journal Works funnels a consideration of site onto each of the singular works. The “bulletin boards” function as locations in which Burr’s inspirations, citations, technicalities, and other multiplicities converge. Site, in this way, is malleable, becoming centralized on tangible square surfaces without diminishing its prowess (one often attributed to spatial grandiosity). The complexity of a landscape is transcribed onto Burr’s Journals for us to read.

Site-specificity is certainly not a stranger to Burr’s practice, especially given that all phases of his work and counting were intentionally housed under the same roof at one point. For The Torrington Project (2021–2024), Burr occupied a former industrial building in Connecticut, arranged a deliberate retrospective of his œuvre, and generated new work in this setting. Though at a different scale in Journal Works, site remains omnipresent across Burr’s artwork. This time, the vertical façade of each piece serves as location in lieu of physical space—perhaps as a map is to a geography, or a blueprint is to a structure. The panels, individually so, become gargantuan through the worlds of milieu they amass. Burr’s fifteen 27-by-27 inch surfaces are site-specific in their own right.

— Emma Huerta

Iiu Susiraja: Touchdown by Venus

Gratin | 291 Grand St, 2nd floor, New York

11 December 2025 – 24 January 2026

The politics of representation has shaped our cultural discourse for some time now. It arose from an urgent need to empower marginalized voices—voices historically suppressed by a hegemony defined by whiteness, wealth, ability, and heteronormative patriarchy. To be marked as “Other” by this order is to encounter structural oppression. As a society, we bear an obligation to resist such injustice and insist on collective flourishing; why should the many suffer for the comfort of the few?

Art inevitably enters this terrain. The sphere of image-making, which I take broadly as a definition of art, is inherently representational. Even non-figurative practices work with matter to produce an image of sorts. Conceptual art, despite its claims to immateriality, still relies on the idea, which requires material undergirding to be formulated (in the body or in computational machines) and expressed. Art, then, is always already a representational practice. In recent decades, however, it has also been tasked with bearing explicit political significance. The justification of art for art’s sake has lost credibility in a moment when everything is compelled to generate (surplus) value within capitalism.

Rising for the occasion, art proposed that representation itself is political. While true, this logic has limits. Representation is a cornerstone of democracy, yet in the political sphere, it only becomes meaningful when representatives enact policies that materially improve lives. Within the art world, representation began as a necessary political project: a means of opening a historically exclusive field. The question remains, however, when this project fulfills its promise, and when it hardens into representation for representation’s sake, leaving its political potential unfulfilled.

Touchdown by Venus, Iiu Susiraja’s solo exhibition at Gratin Gallery, takes a fresh swing at this long-standing debate. Susiraja transforms the gallery into a mute battlefield, staking a claim through self-representation. The exhibition presents fourteen photographs (fine art archival pigment prints) of the artist herself. She appears nude, often meeting the viewer’s gaze, her face marked by the Finnish expression tonnin seteli: the Finnish “expressionless expression.” She is surrounded by objects and props that, according to the press release, serve to “activate her remarkable body.” Susiraja rejects classical depictions of the female form, instead emphasizing her body’s “massive presence in relation to the modest scale of the middle-class, homey interiors in which [her] mises-en-scène unfold.”

In one particularly striking self-portrait, Lift Up, Bottom (2025), Susiraja has her back to the viewer. Two red balloons are attached to her lower back by shiny silver tape. She leans slightly toward a long wooden bench, the sole object in a dilapidated, gray room. While her posture suggests an attempt to merge with the wall behind her as if to disappear, the vibrant red of the balloons forbids it. Instead, they tease a fantasy of flight, as if ready to liberate her from the oppression of gravity. Yet the balloons are clearly insufficient for this task, leaving the artist frozen in an ironic tableau: a heavy, undeniable presence mocking the very idea of weightlessness.

Susiraja’s images demand that viewers confront their expectations of figurative art and question which subjects have historically been permitted within it. As Susiraja notes, “If a fat person behaves badly in an artistic context, then they are doubly misbehaving,” because “an obese person’s simple existence constitutes misbehaving.” In this sense, Susiraja seems to embrace representation for representation’s sake—and yet, her self-portraits refuse to remain politically inert.

— Yonatan Eshban-Laderman

Christine Stiver: The Chicken is Ready to Eat

January 10 – 31, 2026

Tiger Strikes Asteroid | 1329 Willoughby Ave #2a, Brooklyn

In Western European Medieval art, stories about fantastical and powerful animals often reinforced Christian narratives. Artists painted the animals inaccurately, relying on their ideas about what animals might look like rather than on reality or direct observation. In his 1958 poem Bestiario (Bestiary), Pablo Neruda rejected this symbolic tradition, declaring his desire to commune with ordinary animals—cart horses, flies, and fleas—to get to know them well and on their own terms, to see them as formidable in their own ways. He wrote about pigs grunting at dawn, supporting the sunrise. “They hold it up,” he offered, “with their great rosy bodies, with their hard little feet.” From the perspective of our increasingly doom-and-gloom age—one marked by overconsumption, misinformation, exhaustion, and ecological collapse—Christine Stiver’s solo exhibition The Chicken is Ready to Eat at Tiger Strikes Asteroid places her sculpture in a similarly grounded yet playful conversation with familiar yet variously understood animals. Depending on the perspective, chickens are necessarily vigilant or merely panicky. They are symbols of abundance, fertility, and prosperity, omnivores engineered to satisfy mass consumption and sacrificed to honor gods. They fly—just a little—and dwell in their own shit. The roosters among them reliably herald the dawn. Stiver, though, is not particularly concerned with faithful representation.

To make her abstracted, chicken-ish creatures, she uses accessible materials, gathering, cutting, and bending tree branches while they are still green, then fashioning interior paper frameworks that fix the branches into taut loops. She details them with a topography of adornments ranging from exquisite, quill-like, glossy paper coils to dried seed pods and balled-up wax from individually packaged cheeses. She then outfits the forms with bases or otherwise elegantly balances them—on plinths, on the wall, or hanging from the ceiling. For her show at TSA, curated by her husband, the artist Dominic Terlizzi, a flock of these sculptures is arranged in an environment suggesting a chicken coop.

Here, the works read as elemental, ceremonial, and light-hearted, chicken-like and not. Three of them, Wink, Flap, and Squint (all 2025), could be bird masks for a carnival. Shaped like an ear or a prostrate bird, Kneel (2024) features an egg-shaped void near its center. It’s flanked, perhaps to encourage fertility, for good luck, by a legion of the kind of tiny polymer clay charms you can glue to a phone case or hair clip—in this instance, they’re predominantly cartoon representations of hard-boiled eggs. Alluding to flight, Yawn (2024) resembles a tabletop micro-Winged Victory of Samothrace, headless like the mammoth Hellenistic relic but decked out in glassine fringe, seeming both human and avian. The heart-shaped (Pause for Effect) (2025) stands on three pointy paper-pulp clawed feet. The interior structure of this work—at about six feet tall, the largest in the group—involves a quilt-like collage with images of human arms outstretched as if beckoning a congregation to its feet to belt out a soaring refrain.

The constituent elements of Stiver’s works blend into an unpretentious and potent whole, channeling artists such as Jay DeFeo, Carlos Villa, Nick Cave, and B. Wurtz. Though related to the figure of the chicken, what’s at stake is not poultry, not entirely. The common fowl operates as a freighted mirror for our contemporary subjecthood. We are already intimate with chickens: the average American eats about a hundred pounds of their meat each year. Couldn’t we at least admit we are in some ways as vulnerable as they are? Who among us, Stiver seems to ask, can peer into a chicken coop without sharing the cage?

— Marcus Civin

John Kelly: A FRIEND GAVE ME A BOOK

P·P·O·W | 392 Broadway, New York

January 9 – February 21, 2026

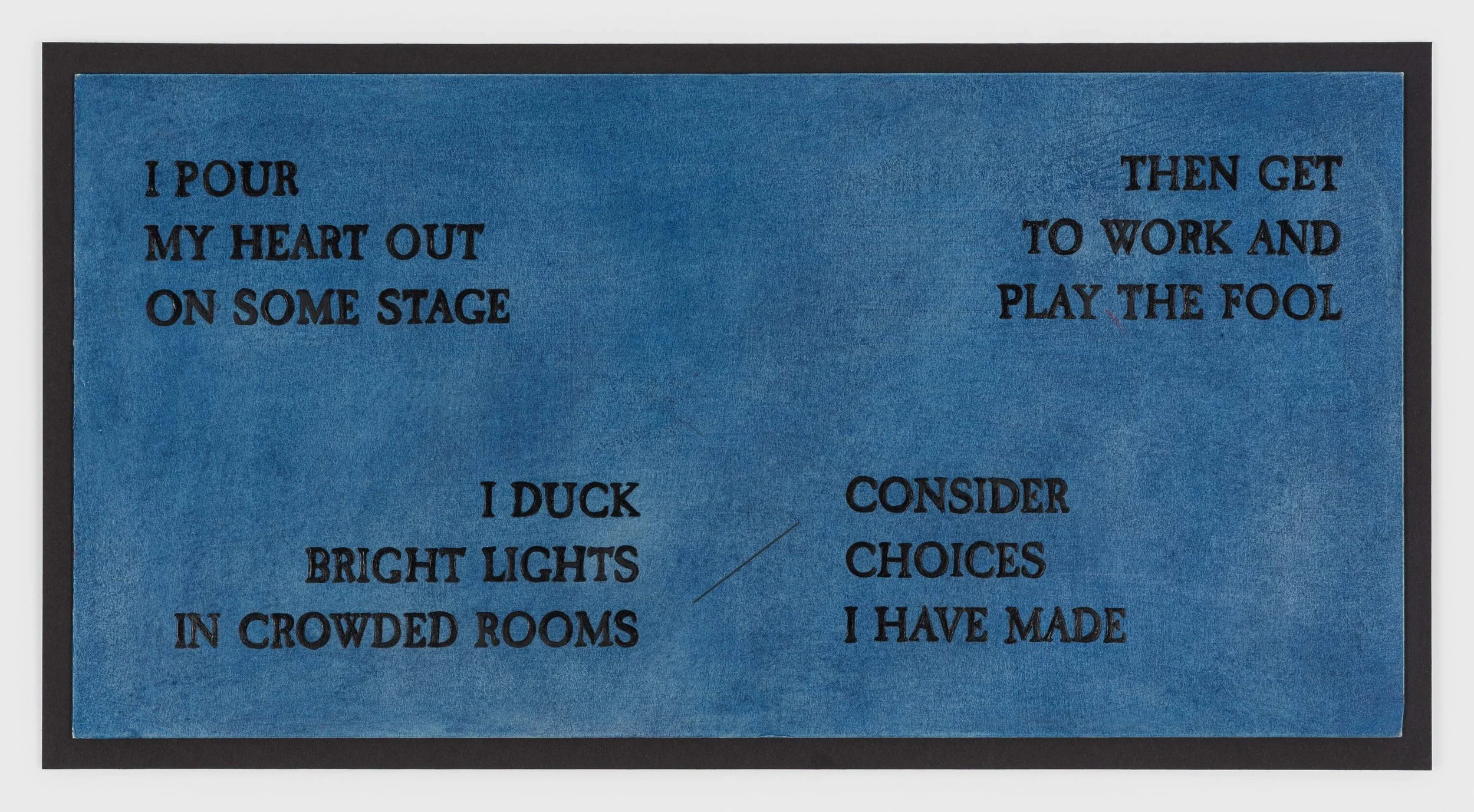

A FRIEND GAVE ME A BOOK, John Kelly’s exhibition at P·P·O·W, turns the white cube into a nervous, run-on sentence viewers must circle to read. Extended friezes of small painted panels spread horizontally around the gallery walls at chest height. From a distance, the works cohere into a continuous band: part filmstrip, part medical chart, part memory palace built from thumbnails. Up close, that continuity fractures into quick cuts: landscapes, cropped bodies, diagrams, and blocks of lettering that flicker between declaration and signage.

Kelly’s paintings are a choreographic exercise in confounding a biography. Clustered paragraphs of two-row grids sometimes tighten the narrative, condensing meaning and deciphering keys in just a few panels, and other times loosen the intensity of one climax after another. Often, a panel finds its mirrored subject, correspondence, or answer across the room so that looking is always doubled by the awareness of a second sequence in peripheral vision. Kelly stages a charged trail that recollects every detail of his life/performance. The gallery becomes a sanctuary and exam room saturated in devotion and self-surveillance. Panels that read “YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE,” “ADMIT,” or “GROSS CLINIC” don’t merely caption the work; they name the spectator’s relation to Kelly’s autobiography, that his life lesson could equally be our mantra for living.

A handful of larger text-panels act like chapter headings: “HOME,” “FOCUS,” “THE ESCAPE ARTIST,” “CREDO CREDO,” “FAME,” and finally, “FINE.” Their bluntness is the point: these are public words pressed into private territory, appearing estranged. They are a reminder that when performing the story of the self, there is no homely comfort. Kelly is estranged from the raw materials of his past in this grand performance of self-narration, with each transformative life event becoming intake forms to fill and confession to make. Indeed, “FOCUS” lands as the voice of productivity. These words, read along theatrical yet mimetic scenes of ambivalent eroticism or violence, provide a deadpan portrait of visibility’s machinery: promise of transparency, simultaneous gatekeeping, and the thin membrane of reassurance that a fictionalized version of a life lived will get across.

A FRIEND GAVE ME A BOOK (2011–2025) complicates the biographical and the archival with a durational performance video that stages the hurt body as evidence to be historicized, examined, and mythologized. If the grid offers survival through naming and filing, the moving image returns what resists filing: longing, ritual, the uncanny persistence of bodily overflow.

The show’s final word—“FINE”—reads less as closure than as coping. Kelly doesn’t mock this mechanism, though; he lets “fine” be what it often is: a fragile utterance stretched over pressure, doing its best to hold.

— Qingyuan Deng

AIDS Support Group of Cape Cod’s AIDS Memorial Quilts Exhibition

Provincetown Town Hall | 260 Commercial St, Provincetown, MA

January 17 – 18, 2026

In a rather scathing 2018 critique of the Provincetown AIDS Memorial for the New Yorker, Russian-American author and journalist Masha Gessen wrote of Provincetown, “some parts seem like a gay theme park for straight tourists . . . other parts resemble L.G.B.T. retirement communities . . . there are a few places in this country that feel to me, all these years later, hollowed out by AIDS, and Provincetown is one of them.” In the 80s, they wrote, people with AIDS came to Provincetown because they had no place else to go; doctors and nurses, their own parents, wouldn’t touch them. Provincetown “had no treatment to offer, of course. But it had low rents in the off-season, many queer landlords who weren’t afraid to rent to the sick, an AIDS support group, a gay magazine full of treatment information (I was the editor), and a lesbian town nurse named Alice Foley.”

The AIDS Memorial Quilt exhibition at Provincetown Town Hall this past weekend stands on the muddy ground between the Provincetown that Gessen recalls and the one they find upon their return. Organized by the AIDS Support Group of Cape Cod to which Gessen alludes, the event was open to the public on January 17th and 18th, following a one-night showing of the same 10 quilts—made up of panels devoted to community members who died of AIDS—following a World AIDS Day vigil on December 1, 2025.

Activist Cleve Jones created the first piece of the 50,000-panel quilt (originally called the NAMES Project Memorial Quilt) in 1987 to honor his friend Marvin Feldman. In October of that year, the quilt was displayed for the first time on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., unfolded ceremonially at sunrise to cover a space larger than a football field, as the names were read aloud.

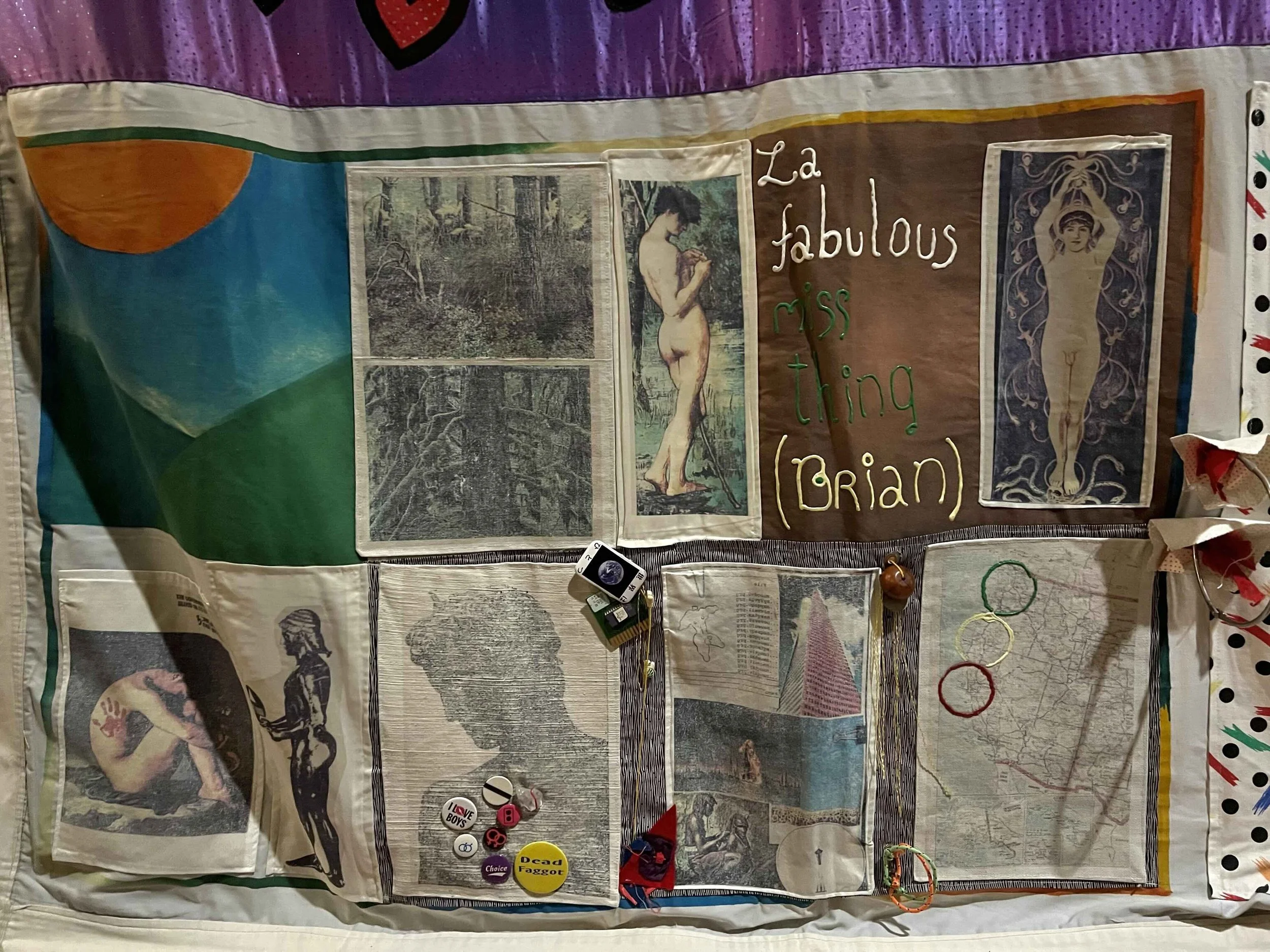

To arrive at the exhibition entails a walk down Commercial Street, past buff mannequins in rainbow spandex and sandwich boards advertising politically-correct drag shows, before reaching the carbon-gray quartzite slab marked “remembering” that drew Gessen’s ire, and climbing the steps to Town Hall. In the cavernous second-story space, quilts stretch across the floor and hang from the balcony overhead. In the center of one work, two silhouetted figures in adjacent panels marked “Todd Peramba” and “Michael D’Augustino” reach for each other’s hands; on another, “Rock Hudson” is spelled out in shimmering silver against a deep blue background streaked with stars, “HOLLYWOOD” arced across a rainbow in the bottom right corner; “La fabulous miss thing (Brian)” is scrawled playfully across another, to which an array of ephemera—floppy disks, bracelets, pins sporting “I love boys” and “Dead Faggot” slogans—is tenuously attached.

It’s easy to bemoan the RuPaulification of the once-scrappy town, to wax poetic about the camaraderie that would blossom on a long summer walk from the beach to the lesbian bar in the days before Hinge. But standing in a room full of hand-stitched, coffin-sized, sequin-strewn memorials, among people who watched their namesakes sicken and die as the world looked away in disgust, petty annoyance and generational self-pity fall away, leaving only what Gessen insists we must hold onto: anger. And it’ll take more than liberal platitudes and glitter martinis to drown that.

— Emma Fiona Jones

Nicolei Buendia Gupit: Handle with Care

A.I.R. Gallery | 155 Plymouth Street, Brooklyn

January 10 – February 8, 2026

Discarded material hangs from the artist’s cast hand: the heavier appendage, disembodied, lifts a lightweight, triangular paper chain net of recycled detritus. Maybe the hand won’t let go because it’s afraid of losing something special. Indeed, the trash would be a treasure for some; the mesh structure is made of shredded balikbayan boxes, a type of corrugated box sent with gifts and essentials to the Philippines from Filipinos living abroad. Bound together with duct tape, Handle with Care (2025) formally presents as a quiet folding of experiences across time.

Handle with Care is Nicolei Buendia Gupit’s first solo exhibition in New York City, following solo exhibitions in other US cities, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Italy. The three-part series of artworks includes, in addition to the cardboard assemblages, a series of immense drawings and mixed media works which explore the same subject matter in further undefinable forms.

The drawings, entitled Witnesses to Empire (1902–1913), (191890–1902), and (1913–1924) (2025), reimagine colonial photographs taken during the Philippine-American War and the American colonial period in the Philippines. In the tender care of her hand, Gupit compares her own family’s private migration archives with public Philippine photographic records. She unifies the human subjects by removing them entirely. In the absence of her photographs’ subjects, traced plants are raised from the background to the surface of handmade plant-fiber paper, positioning the natural world as the primary witness to American imperialism.

Alongside these paper works hang what feels like portraits of a wave. Just as a photographer attempts to capture their subject, handwoven fishing net grasps at the blue textured surface. Gupit’s Silver Linings (2025) series evokes the immeasurably complex emotions a resettling person might struggle with, like a knot in a throat, or an intricately woven rope. Together, the tangled shape of the exhibition recalls the ambiguity of migrant and diasporic experiences. In the sum of these varied pieces, personal narrative through generational memory bleeds into a broader diasporic community across the many histories of displacement.

— Lillian Jenner

[1] Ellsworth Kelly, James Meyer, and Dave Hickey, Ellsworth Kelly: Sculpture for a Large Wall, 1957 (Matthew Marks Gallery, 1998). The full quote reads: “My collages are only ideas for things much larger—things to cover walls. In fact, all the things I’ve done I would like to see much larger. I am not interested in painting as it has been accepted for so long—to hang on walls of houses as pictures. To hell with pictures—they should be the wall.”