Face to Face: December 2025

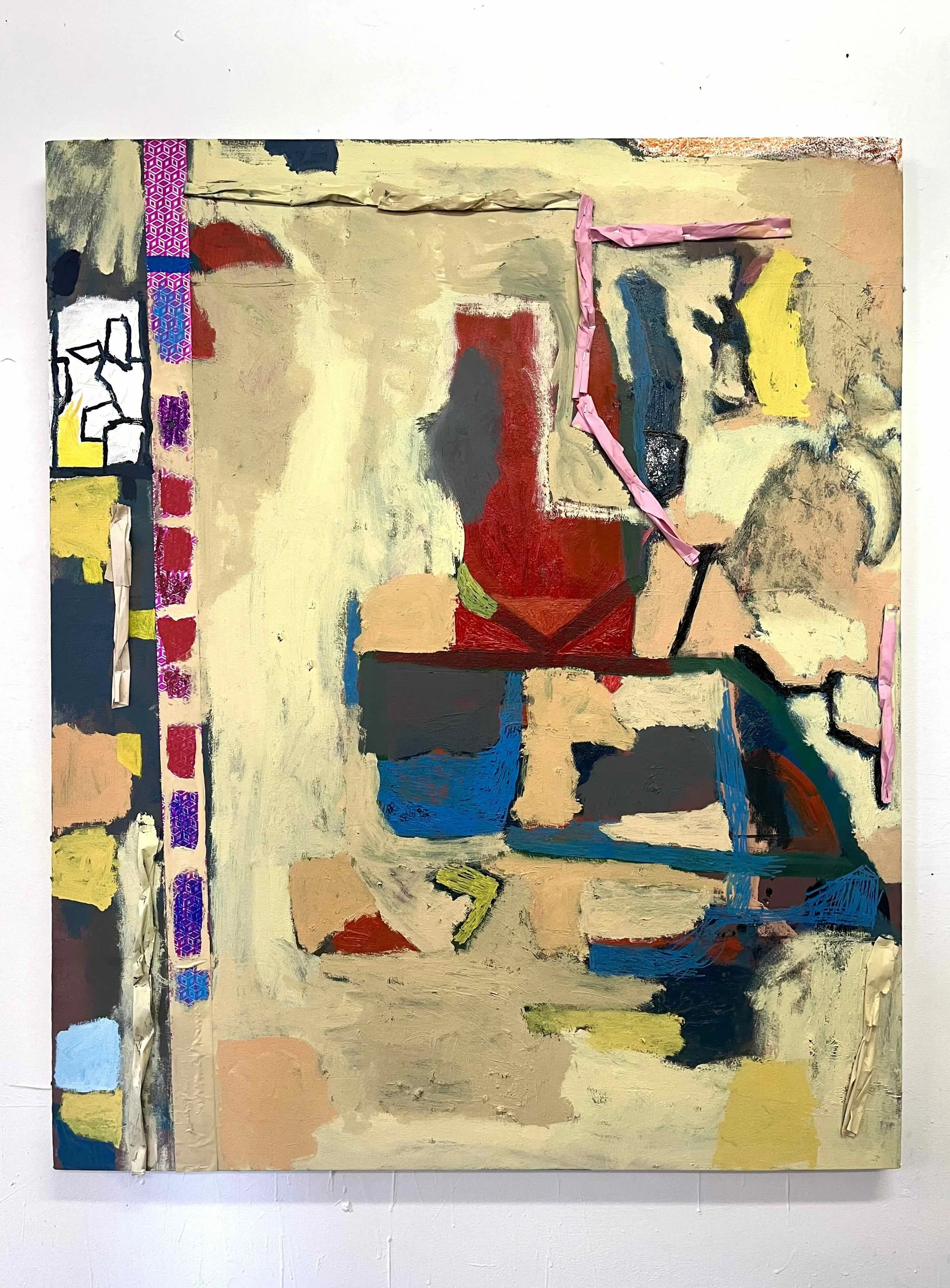

ROSABEL FERBER

Rosabel Ferber’s studio is a playground where the processes of trust and doubt are pitted against each other in the field of painting. A series of colorful gestures unfold across different surfaces and materials, repeating but never the same. There is no set approach or structure that Ferber follows in her work. She does not like the definition of “abstract” painter as that often connotes an original thing which was abstracted, whereas her paintings simply are. Her process is defined by a continuous exploration into the zone of discomfort and failure, where she has the ultimate freedom to fuck up successfully.

As an art teacher of young children, Ferber is fascinated by the uninhibited creative process of kids and how their aesthetic tendencies reveal pre-existing, almost primal preferences towards certain shapes, colors, or images. In the studio, she continually asks herself the question, How does Rosie want to organize space? Reaching a state of play is when the painting begins to flow and evolve, but it requires constant sacrifice, detachment, and letting go. There is a balance to each canvas that places the whole over the individual parts; repainting one area restructures the entire playing field, and can completely tip the scales.

Ferber’s paintings only really begin once something in them has failed. The constant discovery that takes place in her work requires great loss, which she has no time to mourn. Different from a “failure,” a painting that doesn’t work is deemed “insecure.” An insecure painting is too caught up in its perceived reception (the gaze of the Other) to take the necessary risks. The field of mistakes is inexhaustible and infinitely unfolding. To traverse it requires an enduring trust, maybe even faith, in the next mark, the right color to be found, the newest shape to be discovered. The same result never occurs twice. Like a relationship, there’s something undeniable when a painting simply doesn’t work.

Everything in Ferber’s studio is contingent on timing. Multiple paintings are arranged on each wall to allow things to converse, harmonize—a whole chorus emerges. Rosabel keeps “side-pieces”; little paintings on the floor or hanging next to larger works, which she works on periodically in between bigger gestures. These side-pieces receive the least thought; they are the periphery, the marginalia, and yet they sometimes outshine the sole focus. They collect in-between moments, transitory thoughts and movements that allow for the most radical detachment.

You could say that Ferber’s work demonstrates a profound love affair with painting, but it’s not so much painting-as-love object as it is making, or to reduce it even further, doing. If Rosabel’s work were to proclaim an ontology, it would be that to do is to be, and to trust is to do well.

— Jonah James Romm

ANNA TING MÖLLER

Stepping into artist Anna Ting Möller’s studio is more akin to entering a Frankensteinian laboratory. Flesh-like panels line the walls, while recycled containers filled with kombucha sway in cured liquid. Surgical sutures threaded through stretched kombucha skins hover above plaster casts of limbs. Nearby, additional plaster casts made from cauliflower decorate the floors. One cannot help but notice the extent to which Möller adapts their space to the needs of their materials, a kind of surrender that is both delightful and terrifying, as though the materials might come alive at any moment.

Before meeting Möller, I knew of them as the grandparent to a kombucha mother. During a trip to China in 2015, undertaken in search of their birth mother, whom the artist was ultimately unable to locate, Möller inherited the kombucha mother from a woman who hosted them. Through subtracting layers of skin from the kombucha mother, Möller creates works that require them to actively nurture and maintain the kombucha and subsequent offspring’s lives.

Through processes of subtraction and casting, Möller denies the fetishization of origin, exposing the limits and potentialities of hybridity and doubling. Their work positions the viewer as a witness to a form of parenting that aligns more closely with the term’s own linguistic parent: parēns, the Latin term meaning “to bring forth” or “produce.” In this sense, mothering is but an endurance performance for the artist, in which the long-standing relationship between artist and material tugs at the seams of kinship and consanguinity. How does mothering as an artistic practice rupture the means of production?

As we spoke, cross-legged on plastic stools, Möller laughed: “A lot of people have told me my work is disgusting, and I’m okay with it.” Performances such as Whip and Tongue (2024) and, more recently, Smuggled (Version II) (2025) engage the sensitivity of kombucha through sound, movement, and texture, producing an aversive experience through the material’s slimy uncanniness and proximity to flesh. In the former performance, for example, Möller breathes through tubes connected to the kombucha; with each exhale, the material swells. As the kombucha relies on Möller for activation, the artist embraces the corporeal choreography, or citation of corporeality, that emerges from the animated material. As the mound of kombucha jiggles and expands, disgust and desire function as vectors of orientation, magnetizing or repelling the viewer from both the kombucha and the artist themself.

As I prepared to leave the studio, I waved at Möller and the materials that swam in recycled Tupperware. They might remember me when we meet again.

— June Kitahara

KETTY ZHANG

A light breeze carries the scent of distant incense sticks, just as the crickets slow down into a gentle rhythm along with the flutter of wings and broken chirps from the trees above; wet stones lay a path through a bed of grass to a shrine up ahead. This is not the environment we are allowed in our corporatized, concrete-bound lives of traffic noises and the fleeting comforts of matcha lattes. Shrines today are relegated to white-walled interiors, rather than surrounded by natural splendor. Ketty Zhang envisions new private structures for a new mode of prayer.

Zhang’s constructions are fed with adornments and offerings, leaning towards a service for the object, rather than the object as service provider. Almost through a religious act, without the burden of strict universal dictums, these pieces open up a space for personal projections, aspirations, and intimate dialogues. As we live on in this post-Labubu era steeped in extremist oppositions, luxury pop, and pointless functionality, to merely be in the presence of such an object could be a revolutionary act. They also play a unique role in tracing lines between desire and devotion, meeting somewhere in the middle and constantly negotiating a balance. As much as the fetishization of a certain element can produce a sense of power emanating from within it, and however central this may be to the urges underlying desire and devotion, they also have to do with an understanding of power. Do we submit to the artifact, or do we crave a certain control over it?

Shrines and altars are conduits to a world beyond ours. They are portals of communion and communication. She speaks of these as containment, but what exactly is being contained? Not any one thing, that is for sure. Zhang’s practice demonstrates a profound diversity of ideas through her inquisitive exploration of objects as vessels of cultural memory and emotional resonance. Her work navigates the space between mythical longing and material reality, invoking references such as Chinese fables to examine the precarity of existing between known and unknown worlds. This exploration extends to intimate domestic artifacts, where an autographed photo of actress Chu Hai-Ling and her mother’s teaching worksheets become portals into her parents’ immigrant experience—capturing both their former vitality and the strength required to build new lives.

In other works, assemblages of grading sheets, magazine clippings, stamps, abalone shells, choir music, and religious bookmarks create layered narratives that move fluidly between personal history and collective diasporic experience. Through these carefully selected objects, from traditional Chinese medicine materials to Christian and Yoruba spiritual texts, she investigates how displaced identities find expression in the accumulation of cultural fragments, examining belonging, placelessness, and the multifaceted nature of spiritual and cultural inheritance across generations and geographies.

The contemporary altar is as much a nightmare as it is an essential escape from fast-paced consumerism. Whether one looks at these as a pantheon of well-crafted satire, or the foundations of something far larger beyond material understanding, what may remain true is their place in the arts today.

— Abbas Malakar

OISÍN TOZER

Oisín Tozer is interested in stopping time, or at least, creating the illusion of its suspension. “You can see each individual mark,” he says, gesturing to the rhythm of the woodcuts. “When you’re spending time with the work, you can kind of construct a sense of time from it.” Tozer is often asked how many hours a single piece requires, and it’s a question he welcomes. To him, if a viewer is trying to “construct a sense of time,” they are not passively looking, but fully experiencing. Curly wood shavings lie scattered beneath his works, belying how they are made. There is a sense of entropy here with the image on the ground being a dispersed, shattered reflection of the one on the wall. Tozer invites viewers into this non-linear dialogue, leaving a privileged pause to wonder: if time stopped for the artist during the cut, might it stop for us now, too?

For Tozer’s first solo show in the UK, it was the weeds growing in the courtyard of Apsara Studio, a former fireplace shop in Battersea, that stood out. These marginal species are now immortalized in dark birch ply, a chiaroscuro rendered through violent slashes and delicate incisions. When asked about this friction, Tozer pivots to the science of the soil, sharing that these specific plants are used for soil remediation, healing the ground by extracting toxins. “The work speaks to our extractive relationship with nature,” he says, noting the irony that healing requires a kind of theft. It is this inherent violence of taking and reshaping that he hopes the carving carries.

Working from a studio in the Phibsboro Tower in Dublin, Tozer interrogates the human tendency to marginalize and reshape nature, especially in light of ecological loss and destruction. He adopts the rhizomatic philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari with non-linear systems dictating the sprawl of his compositions: “I wanted the practice to have a breath and a scope and an ambition, but not to be linear and prescriptive and didactic.” Mirroring the weeds thriving in the cracks of the dominant system, Tozer’s murals pull the eye into a non-linear network of growth that subverts the geometry of the gallery. Elsewhere, Tozer’s multi-disciplinary reach extends to chlorophyll, a fugitive medium that evolves and fades throughout its life in the gallery, existing in a constant flux-state.

“Weeds have this life cycle outside of our awareness,” he notes. The exhibition becomes a site where this independent rhythm is finally synchronized with our own, if only for the duration of the show. Tozer’s work fosters a quiet, visceral awareness of our own entanglement with the natural world, and, like the rhizome, it stubbornly thrives and quietly persists in the cracks of our consciousness.

— Paige Miller

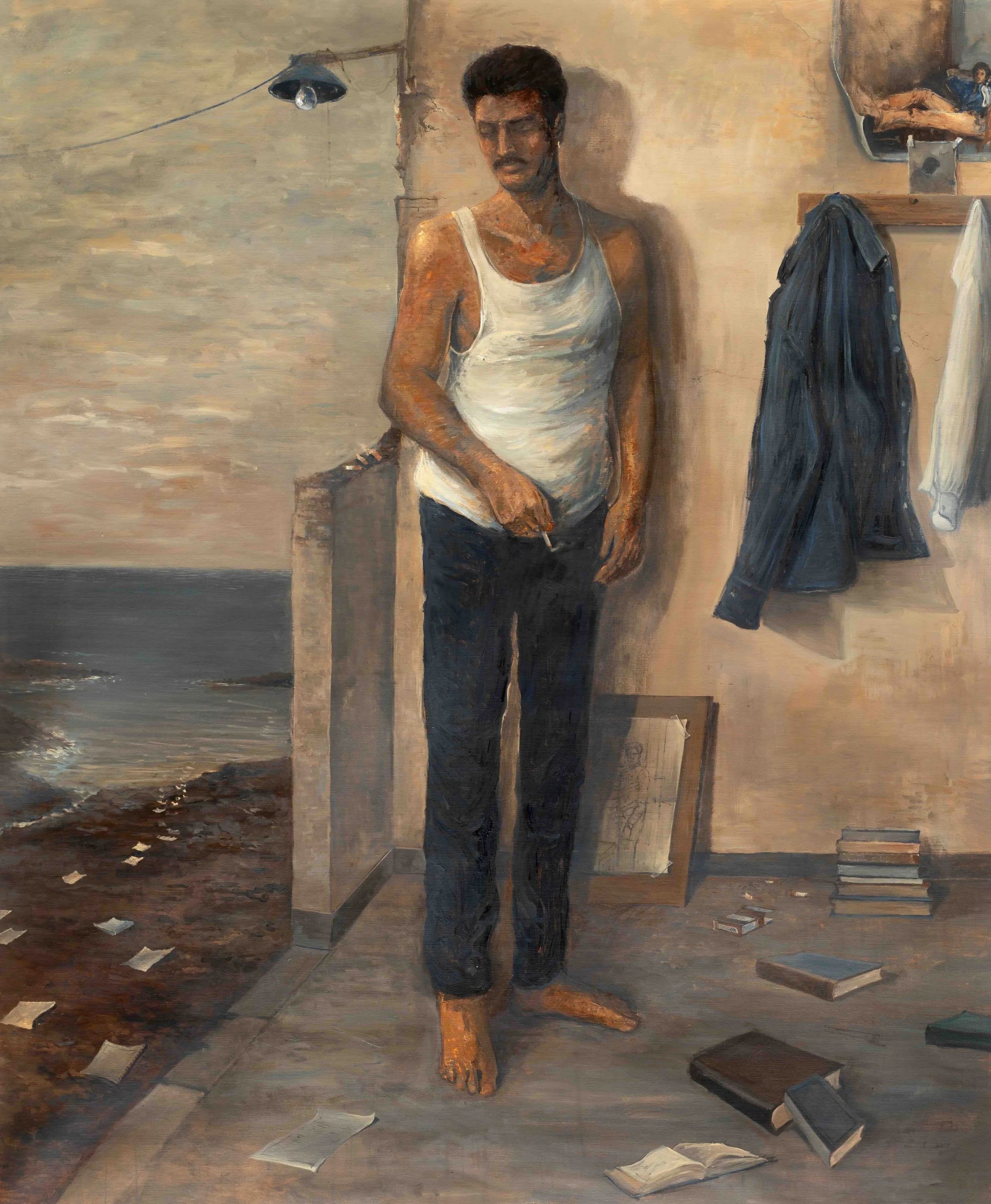

ZAAM ARIF

The rhythmic scratching of a paintbrush dipped in brown slowly covers the expanse of a canvas. Across the lightly painted wash, layers of turquoise pile on as a pensive figure emerges beside. Tall and wearing a simple white vest, Zaam Arif paints figures who seem to continue his train of thought. Although created by Arif, they wander far beyond their origins, leading their own journey after being brought into form by the artist. Inspired by poetry, French and Russian philosophy, and old South Asian films, Arif often takes inspiration from how literature and cinema sprout from an existing framework within him.

This framework, moulded by his surroundings, gets its space to wander through his painting practice in his garage-turned-studio in Houston, Texas. “This isn’t a day studio. It’s a night studio,” he says, as a large canvas hides behind him. “Usually, I enter the studio around 8 to 9 pm, and then I stay in the studio until 6 am, sometimes 4 am.” The canvas, and its emerging composition, is gradually moving toward a form inspired by a Satyajit Ray film, and was presented at Art Basel Miami 2025 with Vadehra Art Gallery.

“There’s always a painting inspired by Camus’s The Stranger,” he says as he talks about the shows he worked on in the recent past, including Deewar at Frieze No. 9 Cork Street with Vadehra in London, or Lost Time with Night Gallery in Los Angeles, both earlier this year. Arif read The Stranger at a young age. Written in 1942, the French novella captures what Camus termed “the nakedness of a man faced with the absurd.” Perhaps the artist’s practice is a prime case of how art and literature can shape our inner world. Arif’s figures embody his introspective nature, holding their poses long after the painter has left his studio.

— Shreya Ajmani