Su-Mei Tse: This Is (Not) a Love Song

Stones, shells, soil, pine needles, images, and words: these are some of the objects Su-Mei Tse accumulates in This Is (Not) a Love Song, her sixth solo exhibition at Peter Blum Gallery. Across photography, sculpture, and installation, collecting is the Berlin and Luxembourg-based artist’s primary creative tactic, while the extent to which it entails direct appropriation varies from work to work.

With Meltemi (Aegean Winds) (2025), Tse collected the sculpture itself, much in the tradition of Marcel Duchamp’s readymades. Over the phone, she tells me that while hiking with her daughter in Greece, she found the nest-like tangle of pine needles exactly as it appears in the gallery. “It’s a wind-made sculpture,” she explains, “and when I found it, my daughter was laughing. Then we went to dinner, and I had it under the table, and there were all these cats coming over because the pine has a certain smell. She had to protect it!” Lifted from nature, the needles became sculpture through a quintessential gesture of collecting—complete with possessive safeguarding and entombment beneath a vitrine.

By contrast, the two spheres of compacted earth in the exhibition—one a component part of the installation God sleeps in stone, the other entitled Dorodango (big), both made in 2025—add manual intervention to the creative process. Drawing on the Japanese art form of dorodango (literally “mud dumpling”), Tse molds and polishes soil into gleaming orbs, appropriating a folk practice as much as the loamy ground itself. “Each dorodango has one origin,” she notes. “I take the soil in a pure way so there’s a uniform grain.” In this sense, Tse is also collecting places, a strategy that closely parallels her photography.

Pictures such as Japanese Garden (Kanazawa) and The End of the World, both 2025, offer visions of specific sites. For instance, the latter depicts the Mediterranean Sea as seen from the southernmost tip of the Greek Peloponnese, locale of the mythological Cave of Hades. Gazing off to the horizon, back turned away from the entrance to the Underworld, Tse is a traveler capturing dubiously indexical snapshots along her journey.

The End of the World is not merely a photograph, though, but a compound work comprising a framed text on paper: I can’t remember how long I’d been walking. The path was stony, arduous, and austere, when suddenly I was right there. I’d been searching for it for so long! And I turned away leaving it behind, and gazed into the distance. Though visually marginal, these typewritten words are, according to Tse, “as important as the classical view of a seascape. Here, I see myself as a writer rather than a photographer. The image illustrates the story.” This interrelation between media is yet another turn of the screw away from collecting as direct appropriation. Not only are the components shaped by Tse’s own hands—through camera and typewriter alike—but the total work coheres through her combinatorial authority, her personal imposition.

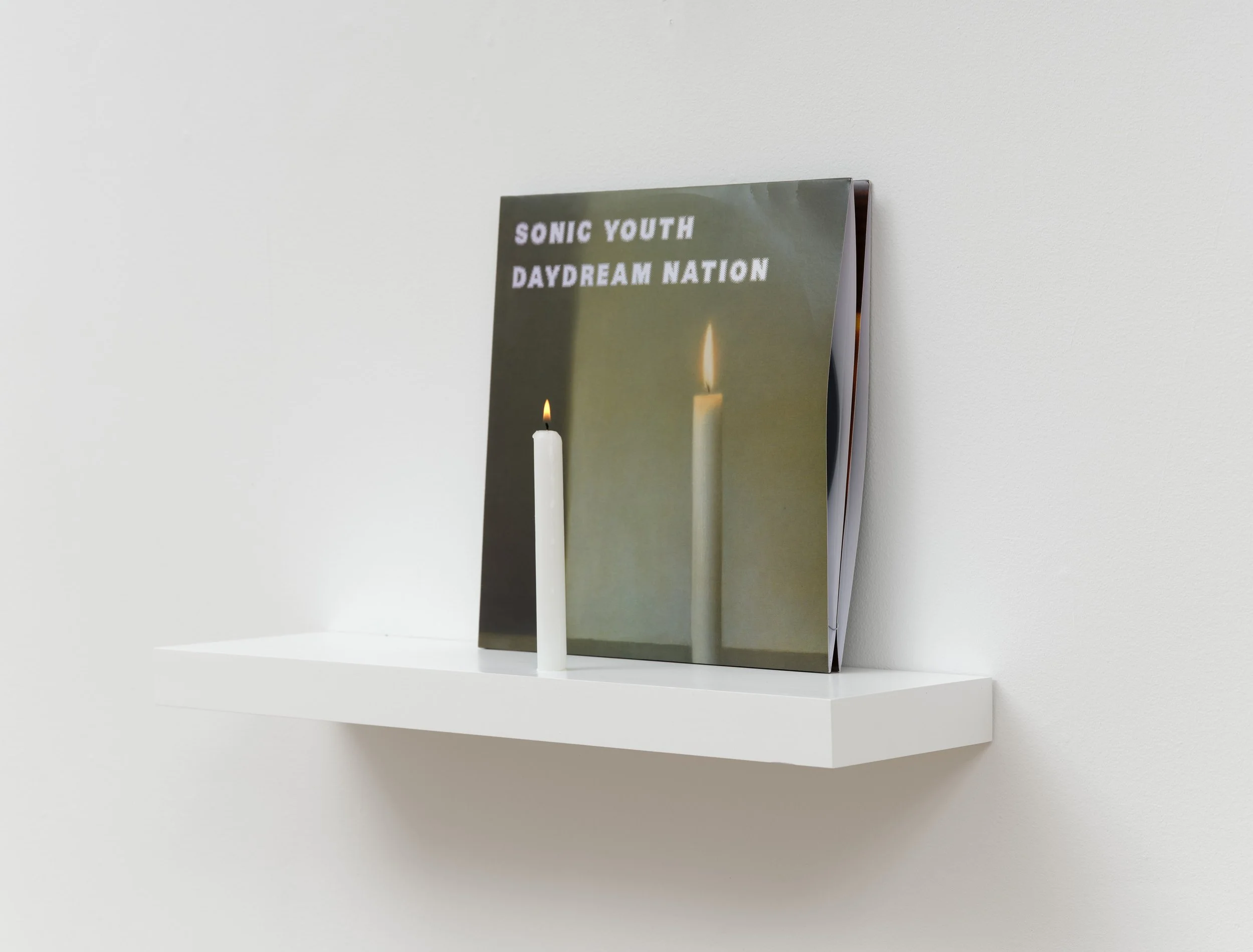

Daydreams (2024) extends this logic still further. On a shelf rests Sonic Youth’s Daydream Nation, a favorite from Tse’s adolescent punk years. Its cover image reproduces Gerhard Richter’s 1982 painting Kerze, another long-held favorite. In front of this image, Tse places a real candle, burning and flickering on the shelf. “It was a simple gesture,” she recalls. “I did it very spontaneously. You have these layers of references to things that I like, which can be heavy, but they’re also just everyday objects.”

At once musical, visual, textual, and sculptural, the installation attains a staggering complexity of signification for an artwork so casually assembled. Tse is, among other things, holding up a light to her idols, paying them a kind of homage; she is directly appropriating their work, bearing their influence; and she is lighting up the gallery, perhaps bidding her audience to daydream therein. To see all this in the piece is to approach it not merely as an LP, but as an album, from the Latin albus (white)—a blank volume filled with discontinuous bits and pieces. Populating the gallery with all these objects and images, Tse seems to me to gesture toward cycles of life and death, collection and dispersal.

She responds to this interpretation carefully, as if laboring to articulate a slippery intuition without losing it: “Everything is there. Things happen with a certain distance. In the process of creating, it’s about combining or revealing things. Reading is really what I feel the closest to.” In another idiom, the death of the author is the birth of the reader. Collecting, creating, appropriating, reading, and writing—these concepts begin to imbricate beyond clear distinction in Tse’s work.

Consider the photographs Bird Song and Love Song, both 2025: birds perched on telephone wires and a plant’s dangling vines are bits of musical notation as well as illusions of dye on paper. Indeed, just what these objects are, the very nature of their creation, is entirely dependent upon how one reads them. At least, that is how I read them.

Su-Mei Tse’s This Is (Not) a Love Song is on view at Peter Blum Gallery from November 21, 2025 through January 24, 2026.