The Prefix to Shatter

The lexicon of precarity continues to saturate Charisse Pearlina Weston’s works in her debut show with Jack Shainman Gallery, mis-/mé- (squeeze). Yet while anticipatory shatter endures in Weston’s floor-bound glass sculptures, a different kind of peril, and thus a required tenacity, prevails as she moves works to the wall.

Entering the gallery, the viewer is greeted by the freckled, clinical inkjet expanse of gesture toward . . . where ‘were’ creeps slowly across the field (2025). For this work, Weston manipulates photographic documentation of her past installations, magnifying details of glass, which render the material alien. Through this enactment of repetition, Weston orchestrates an encounter like that of surveillance. How do we recognize? What are the dangers that persist in the fragments of misrecognition?

The threat of misrecognition, as prompted by the title’s synthesis of mis- (Old English for “wrongly” or “amiss”) and me- (Latin for “less” or “badly”), lives on in its capacity for incongruency. The exhibition marries these two etymologies to describe the impact of erroneous judgment in processes of identification. Such conditions—one of simultaneous invisibility and hypervisibility—evoke what Weston calls the “squeeze,” which articulates such oscillatory duress on Black visibility. As the artist distorts and reconfigures surveillance glass and mirrorpane, the phenomenal transparency manifests the conceptual “squeeze” by presenting the illusion of access to interiority. In looking through the glass, we are met with resistance: another pane of glass, or rather, another beautiful and impenetrable surface.

As the exhibition unravels, the viewer encounters Weston’s interest in the formal gesture of the fold, which invites the issue of excess. untitled (after the squeeze and the fuse and the lift) (2025), which spills over a pedestal cliff, presents a union between a drooping panel of lead, layers of fused mirrorpane and Solarcool breeze glass. At first glance, the amorphous form is weighted with cool sensuality. After a double take, the viewer catches their own pliant reflection, a disarming detail which Weston duly notes in the materials list: “Solarcool breeze surveillance glass.” Nearby, A misprinted aesthetic ligature touches . . . (2025) hovers like an oceanic plane, fractured and folded into elegant multiplicity. The outward creases of inkjet print jut forth in excess, joining the “squeeze” with Nicole Fleetwood’s concept of “excess flesh.” Concerning the United States’s cultural obsession with racialized visibility, “excess flesh” attends “to ways in which black female corporeality is rendered as an excessive overdetermination and as overdetermined excess.”[1] In Weston’s billowing sculpture, excess is presented not necessarily as a re-inscription of corporeality, but as a manipulation of material that leaves the viewer’s gaze to linger on the surface. The frayed edges of crushed, tempered glass drift towards an eventual disappearance, where, even in the absence of a body, the fold becomes a figuration of such visual constraint and scrutiny.

Weston’s sculptures are sedative, just as they are a theater of materials on edge; they are works that reveal how racialized visibility is under duress as much as it is made to disappear into the structures of the everyday. Composed of geometric, concrete blocks which prop up Mediterranean blue glass panels, I belong to the long past that lends colors to the vain (2025) seduces by way of its sharp angularity. The tipping vertex of glass sinks into perpetual slippage, leaving the panes buoyant and calculated. Beside it, I am alive although I cannot see myself and cannot speak from there or make my self speak words stuck just below the surface (2025) beckons the viewer to crouch. Here, a single sheet of tempered, laminate glass tightropes between two concrete arcs. The concrete supports, which at first glance seem like the sole points of balance for the thin glass pane, reveal a trick: the glass depends not only on the concrete but also on its own weight for endurance. Precarity is no longer bound solely to the register of emergency. Instead, the viewer is made witness to precarity as a durational quiver and balancing act; a difference in weighted distribution.

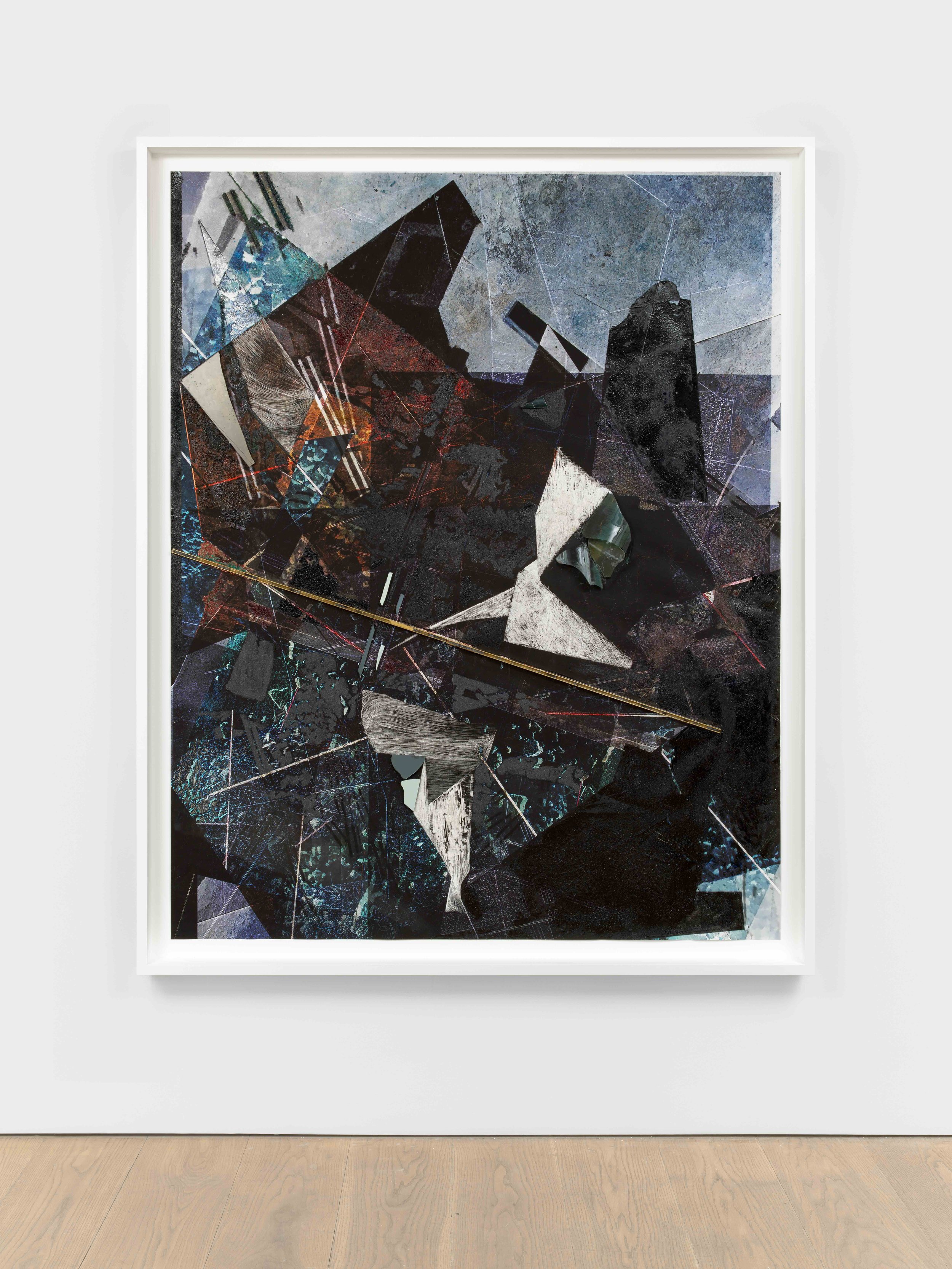

Compared to the freestanding sculptures, the wall pieces initially seem less dangerous. Through the risk of the viewer committing accidental, loose-limbed violence may have lessened, Weston relocates the threat to the visual. Our gaze can commit the shatter or become witness to its afterlife. Facing the cosmological swirls of . . . else-where. (2025) and II. mis-titled (2025), the viewer is required to squint at the wafting pieces of glass, or glass already broken and violated. Weston names this debris the “after-being of collapse,” a syntax of ontological and visual rupture that describes perpetual misrecognition and sustained endurance even in fragmentation. Do we recognize the shatter or do we simply see glimmering shards? Whether glass folds, looms, and bends over from the wall or two balanced panes of glass teeter on the edge of joint destruction, this exhibition argues that this enduring pressure and therefore, perennial resistance, persists just the same.

Charisse Pearlina Weston: mis-/mé- (squeeze) is on view at Jack Shainman from October 30 through December 20, 2025.

[1] Nicole R. Fleetwood, Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness, (University of Chicago Press, 2011), 9.