Self-Portraiture and the Opacity of Class

When Willem de Kooning proposed that paint was invented because of the existence of flesh, he may have meant it both literally and metaphorically: we feel compelled to mimetically recreate our existence through other means, like paint, and thereby create some equivalence between the substance of paint and the unrelenting materiality of our bodies.[1] This de Kooning quote sprang to mind upon seeing Samuel Guy’s self-portraits in Hitchhike from Saginaw, on view at Auxier Kline. Guy uses oil paint so unsparingly and so thickly to render his self-portraits that it is as if he is trying to bring forth not just paintings but real characters, hosting these different selves that have no basis in his physical life but still somehow, obliquely, exist in him as fragments.

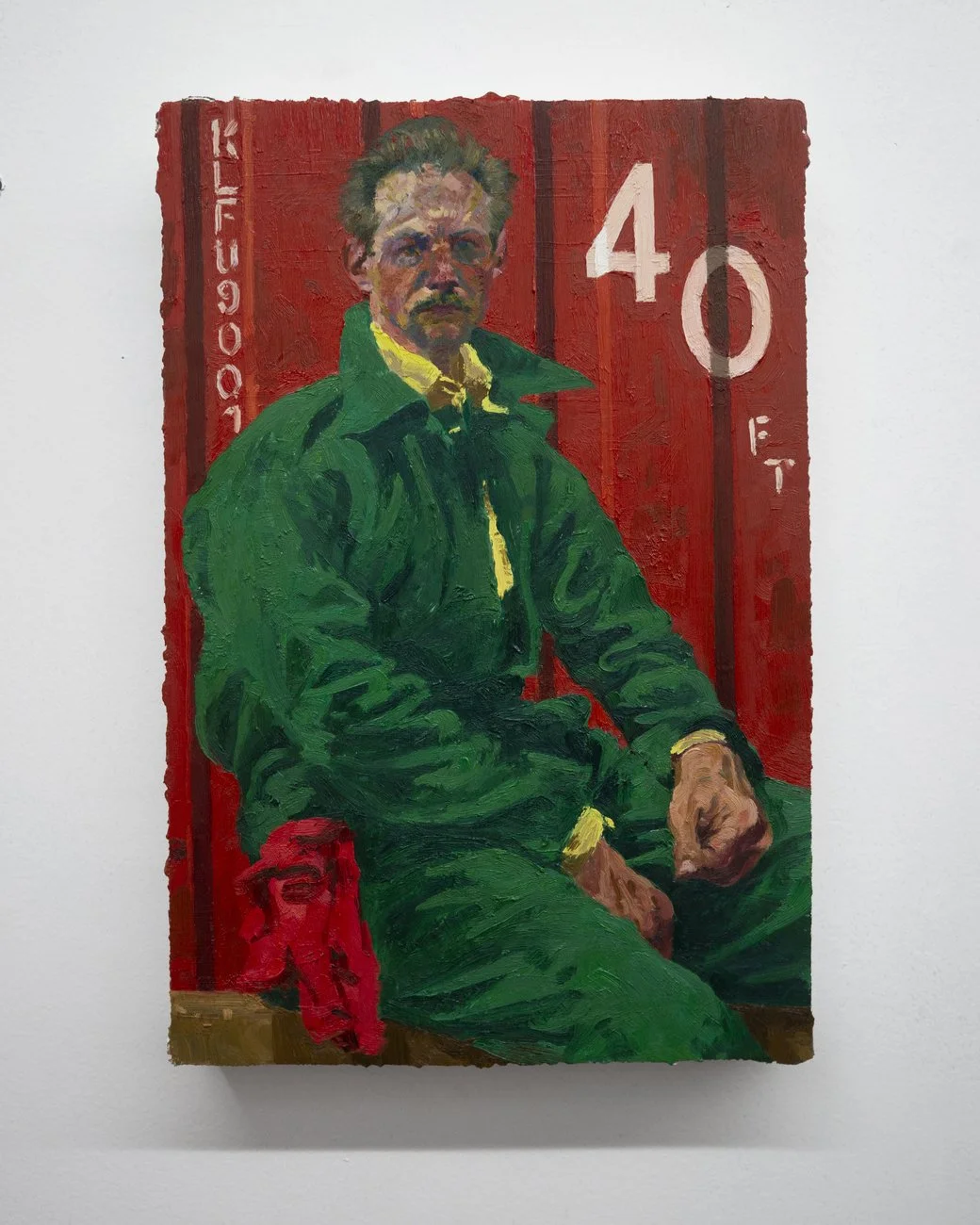

The eleven works that comprise this exhibition continue Guy’s engagement with the genre of self-portraiture. Each features his face, but takes on a different masculine archetype culled from middle America: the salt-of-the-earth prairie farmer, a rural school principal, a fisherman, a gas station mechanic, among others. These portraits of self-fashioning and self-performativity, drawn from the artist’s love of vintage clothing, are neither ironic disavowals of these masculine mythologies nor thoughtless celebrations of them.

Lieutenant (After Bouveret’s Woman from Brittany) (2025) depicts Guy as a Vietnam War veteran, a composite character recalling the likes of Lieutenant Dan from Forrest Gump, or perhaps less optimistically, Water Sobchak from The Big Lebowski. A surprising art historical reference scaffolds the work: Woman from Brittany (1886) by the 19th-century French painter Pascal-Adolphe-Jean Dagnan-Bouveret, rendered in Bouveret’s trademark naturalist style. In Guy’s version, he replaces the woman’s Breton coif with a bandana, a now-recognizable sartorial marker of Vietnam War veterans and therefore a kind of isolated sign that circulates as a cultural fetish.

Prairie Man (After Clausen’s Brown Eyes) (2024) inserts an idealized latter-day “pioneer” into Sir George Clausen’s 1891 painting Brown Eyes, in which a young peasant girl looks out over our shoulders beyond the canvas. The only truly dark part of the painting is her eyes, which hold the emotional weight of the work. In his painting, Guy has swapped out Clausen’s figure of naïve beauty for a ruddy prairie man who looks unflinchingly straight at us, his face and hair composed of the same flitting brushstrokes that materialize the open fields behind him.

These self-portraits not only underline a certain performativity that is inherent to any kind of subjectivity, but they also comprise a composite portrait of a certain American class: the mythic men who (unwillingly) symbolize the economic decline that has beset much of rural America. Often overlooked in national discourses, the slow apocalypse that is the decay of the Rust Belt and its devastating effects of job loss, drug epidemics, and generational poverty has, in recent memory, enjoyed a modest resurgence of attention through figures like JD Vance and his 2016 book Hillbilly Elegy, but it still stays at the level of a political project with improbable solutions rooted in traditionalist nationalism or the revitalization of American manufacturing.

Guy grew up in Binghamton, New York, where he witnessed firsthand how the collapse of once-robust cities, hollowed out by de-industrialization and the offshoring of production, coincides with the decline of local cultures and a pride of place. Binghamton, one of the most northern Rust Belt cities, was not hit as hard as other former industrial hubs, partially because its economic stagnation was buoyed by the city’s longstanding technology industry. However, it is unlikely that Binghamton’s postindustrial stakes in the tech industry will bounce the city back to its pre-1970s level of productivity.

Guy’s invocations of different masculine Americana identities suggest a use of the self-portrait as a speculative act rooted in empirical fact (there probably is, for example, a gas station attendant in Ohio who looks like the man in Guy’s Forty Footer [2025], or a genteel rural farmer who dresses in LL Bean and wields an axe, like in Guy’s Axe [2025]). The goal of self-portraiture, in Guy’s hands, is not to cling to the illusion of an inviolable, unified self, or to indexically guarantee presence through image, but something weirder, like the self-portraits of John Coplans or Nikki Lee, which are more concerned with self-portraiture in relation to extreme self-objectification. Like Coplans’s self-portraits, his body parts warped and cropped to the point of misrecognition, or Lee’s 90s ethnographic self-portraits that provocatively suggest identity as both utterly superficial and deadly serious, Guy’s self-portraits are explicitly representational but not exactly political. They are in thrall of the individual, but not concerned with identity in an era where expression of individualism is proof of one’s subjectivity.

There is a philosophical risk—next to an undeniable visual appeal—to Guy’s self-portraits that suggest how archetypes and tropes simultaneously simplify and complicate the self and how we become what we are expected to perform. The very first line of Nietzsche’s preface in The Genealogy of Morals goes something like this: we are necessarily strangers to ourselves, and each is furthest from himself. I take this to mean not just that it’s impossible to know ourselves fully, but maybe that who we are invariably exists in fragments, and each fragment splinters into further shards, in an infinite regress to the point where identity or selfhood can only really be apprehended in glimpses depending on who we are with, what we’re believing in that moment, what we’re wearing, where we’re living, and all the other specific vectors that govern our life in a given moment. What Guy does is take this idea of the infinity of selfhood to explore the opacity of class experience in end-time capitalism in a particular geographic area, where often class is “something that happens to you, like the weather but worse and more unrelenting.”[2]

Samuel Guy: Hitchhike from Saginaw is on view at Auxier Kline from November 14 through December 19, 2025.

[1] Willem de Kooning, “The Renaissance and Order,” talk delivered at Studio 35, 8th Street, New York, Autumn 1949.

[2] Jedediah Britton-Purdy, “The Remaking of Class,” The New Republic, June 27, 2018.