Through the Flowers

Spots and specks are typically signs of disrepair. Spores of black mold might fleck the corners of a poorly maintained apartment, while rust might muddy the once gilded surface of a building’s frieze. But a more fecund substance dots the paintings of Elif Saydam. Flowers, delicate and diminutive in size, spring up in unlikely places—on the awning of a late-night convenience store, in crevices between cobblestones, and along the edges of a gas station price sign. Some of Saydam’s flowers are roses, a highly charged symbol in the artist’s native Turkey. Others carry a charge of a different sort; in Getting the Slip, Hurling a Brick (2023), daisies fly like sparks in the gap separating two outstretched hands. Fragile chains of blue felicia cascade down the canvas in Cupid (forget me not) (2023), recalling fireflies and fairy lights.

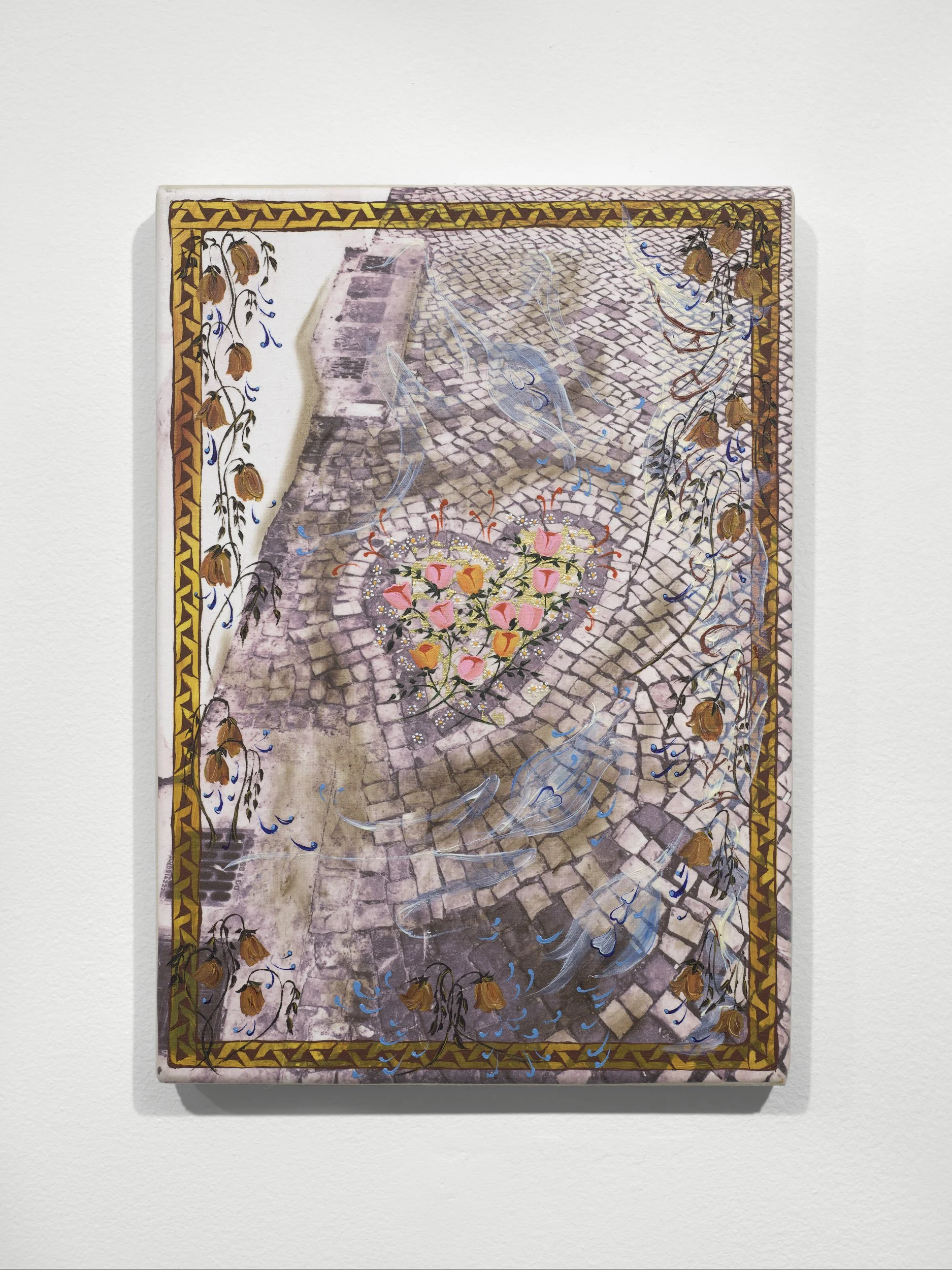

Like a graffiti tagger, Saydam encrusts images of urban spaces with flowers, filigree, and other decorative elements. These ornamentations transform a city’s quotidian sites into spaces of fantasy, while also evoking the histories of minor painting traditions such as Persian miniatures and illuminated manuscripts. As I walked through their solo exhibition List Projects 32: Elif Saydam, currently on view at MIT List Visual Arts Center, I couldn’t help but read that word “fantasy” for its amorous connotations. Hearts of red, gold, and cornflower blue quietly overwhelm the surface of the aforementioned Cupid, as well as THIS TENDER THAT RENT (2022–2023). In the small painting that opens the exhibition, After (THE RENT IS TOO HIGH) (2023), a heart-shaped garden of roses grows on sewage-stained cobblestone, a testament to love’s persistence. “This would be a great show for Valentine’s Day,” I thought, before I realized that I was actually seeing it on the anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.

Saydam has never lived in New York. Born in Canada to Turkish parents, they spent much of their childhood in Turkey and now reside in Berlin. But inspirations noted in the exhibition text point toward their engagement with the city’s queer culture in the interstitial years between Stonewall (which arguably birthed the queer community as we know it today), and the AIDS crisis (which changed it forever). From the paintings of Martin Wong, Saydam inherits an interest in how windows and other openings in urban facades provide intimate glimpses of interiors. Larry Mitchell’s 1977 novel The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions gives them a blueprint for imagining a radical kind of queer sociality. The use of the word “blueprint” here is deliberate—simply put, Saydam’s show is about infrastructure, about how the built environments we inhabit generate eros amid precarity.

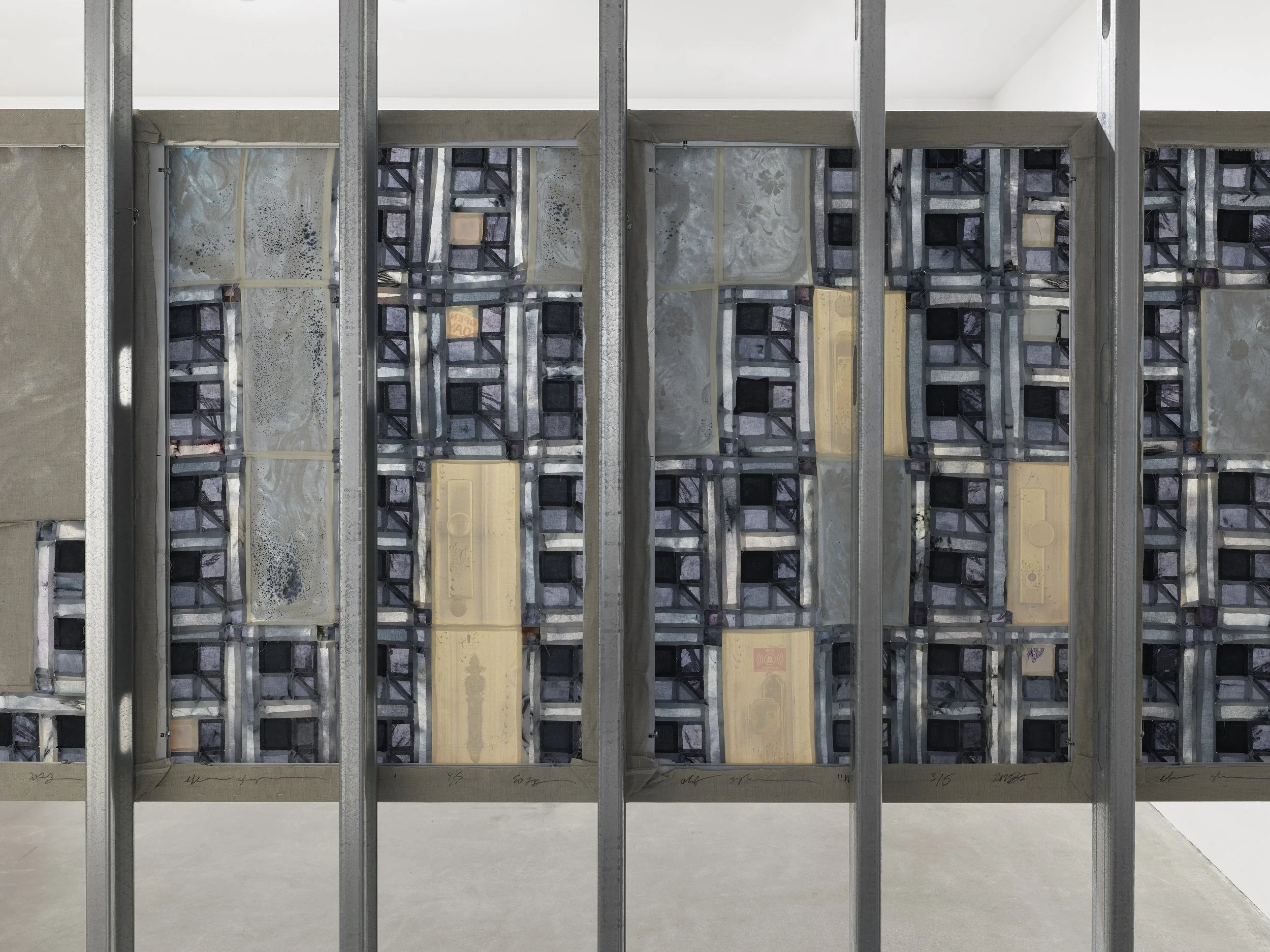

If flowers and hearts are Saydam’s medium, bricks are their substrate. The stretched surface in Cupid is comprised of small rectangles of fabric that the artist has hand-stitched together in a staggered pattern reminiscent of brickwork. Saydam’s iconography is also architectural; in Beusselstrasse 17 10553 Alt Moabit (2022–2023), they build a skyline of batik-dyed cinderblocks embellished with photo transfers of doorknobs in their Berlin apartment complex. A hazy reflection of Saydam’s hand can be seen in each knob. The artist’s hands, I assume, are the ones we see depicted in Getting the Slip, Hurling a Brick. The second phrase in that work’s title underscores an important fact: bricks are not just a building material, but a weapon. Throughout the 1960s, the Stonewall Inn functioned as a red-bricked shelter where queer people could congregate without interference. But when it was raided on June 28, 1969, patrons appropriated bricks for another purpose—to defend themselves against police brutality.

The specter of violence looms throughout the show. Saydam prizes the späti, a type of late-night convenience store common throughout Berlin, for the social interactions it encourages between the city’s various classes. But in Zu spat (VII) aka Leader Nicht (Unfortunately Not) (2023), a security shutter is pulled over a späti door, protecting it from burglary. Blood drips from the arrows that pierce the twin forms in Cupid—a nod, perhaps, to the exquisite masochism of Saint Sebastian. Two painted-over security mirrors prompt us to police ourselves; other forces threaten, too. References to climbing rents abound within Saydam’s titles, imperiling the affordability of neighborhoods that had once provided refuge to immigrants or queer people. Eviction, violence, and surveillance erect barriers to intimacy, particularly for those perceived to be threats to the social order.

Yet eros blooms in the cracks of these barriers. In an interview accompanying the exhibition, the artist recounts their cathexis to a scene in Jean Genet’s Un chant d’amour (1950), a homoerotic prison film. Brick walls separate the inmates, but through a tiny crevice, one flirtatiously blows cigarette smoke to the other. Amid restriction, the men develop new designs of living. It is likely by design that the sexiest work in Saydam’s show is one of the security mirrors. Love Poem (Censored) (2025) is painted with a lattice pattern resembling the geometry of Islamic architecture. Embedded within its filigree is a verse from Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi’s 1197 epic romance Bahramnameh: “He put day’s brightness in the shade: / What talk of shade, with sun displayed!” The piece is hung in the upper corner of one of the gallery’s walls, a playful pun on the traditional placement of convex mirrors like these. But its location also recalls the sun—this is a gesture of “high” camp in the most literal sense. Saydam exalts the debased, elevating eros to a position normally reserved for the divine. It makes me think of another Genet work, one which endows an imprisoned drag queen with a saintly name: Notre Dame des Fleurs, or, Our Lady of the Flowers.

List Projects 32: Elif Saydam is on view at MIT List Visual Arts Center, Bakalar Gallery from June 5 through August 31, 2025.