Interstitial Institutionalism

On March 12, 2025, Alessandro Michele’s first collection for Valentino was staged inside a replica of public bathrooms in front of the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris. Michele attempted to strip away the veil between the private and public dimensions of life, redefining and challenging what is considered public and what should remain hidden.

It’s significant how this “staged bathroom” unfolded in front of a leading cultural institution, notoriously one of the most hierarchical kinds of buildings, where visible and invisible areas are made clear from the moment you enter, whether as a visitor or as part of the team. Following the modernist model established from the 1960s onward, the separation is clear: the gallery is the served space for art, while everything else—storage, offices, bathrooms, lobbies—revolves around it as serving spaces that sustain the white-cube exhibition space.[1]

This model, which has dominated the contemporary art world over the last few decades, is now part of the broader failure of the art institution as we know it: there is less and less participation, with declining visitor numbers, and it is increasingly politically censored. To cure this illness, the fastest solution is usually the creation of sensationalist, aesthetically-prioritized, Instagram-friendly exhibitions, which lower the content level and complexity, but favour, at the same time, visitors coming to take the best selfie or create the best content for social media. The result of these attempts is the origin of the deteriorating cultural space: more like Disneyland, less like a space to reflect on the contemporary issues that affect our society.

Preventing this Disneyfication from happening requires, first of all, a longer-term stance and trust in the people who work in the programming area of the institution. However, more than anything else, it needs a revision of the museum’s architecture and the dynamic of the served and servant spaces inside it. Reshuffling these boundaries is instrumental to regaining traction with diverse and broader audiences. The museum (which includes, for the sake of this article, private foundations and other forms of contemporary art institutions) must consider itself a crossroads where one comes not only to visit exhibitions, but also to linger in the café, relax in the garden, or consult the library. Art must then expand its perimeter, inhabiting these transitional areas. This is when the interstice comes into play.

When discussing the interstice, I refer to the transitional spaces within institutional architecture, such as corridors, lobbies, stairs, and so on. In recent years, these spaces have begun to emerge as sites of experimentation, particularly through performance art, which is inherently malleable and adapts to occupy non-traditional environments. Moreover, the bodies in motion provoke people who pass by to ask questions and spark interest in the building they find themselves in for the most disparate reasons (which, as we saw with Michele’s runway, extend beyond visiting exhibitions).

An antecedent to contemporary spatial practices can be found in one of the earliest pieces by the dancer and choreographer Lucinda Childs: in Street Dance (1964–2025), Childs gathered an audience in her studio on the fifth floor in Chinatown, New York, switched on a tape recorder, and left the building. The tape invited spectators to watch a dance performed in the street below by Childs, along with Tony Holder, and later described the objects and details pointed at by the dancers. Through this displacement, the street became an escape from the canonical space of the artist’s studio—a space commonly referred to as an interstice suddenly became fundamental to the work. The playful, even ironic, and subtle approach of the piece serves as the guiding principle for the two contemporary pieces to be examined subsequently. When facing an unusual space, the performers themselves must be malleable and capable of adapting to challenge informal environments and situations.

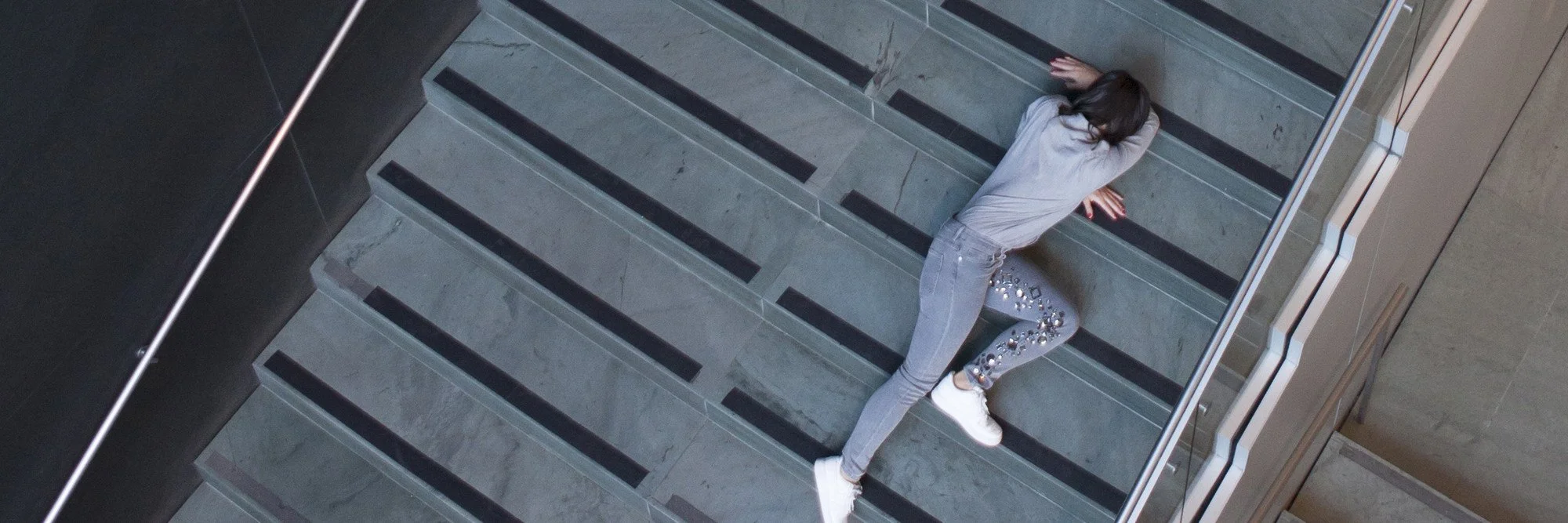

Leaping forward to 2016, we set foot in MoMA. On the second floor of the museum, the Mallon Atrium and the stairs connecting them are inhabited by a live installation by choreographer and performer Maria Hassabi. In PLASTIC (2016), the artist, along with eighteen performers, moves throughout the space for the whole opening hours of the museum at a barely perceptible pace—collapsing down the stairs, taking statuary poses in the lobby, and completely collapsing the distance with the audience. The piece breaks the rules of the museum space: it becomes an obstacle for the people coming through it, and, because of this, it is impossible to ignore. The stairs become the stage for a daily, one-month-long performance. This conceptually (and economically) ambitious piece is not exhibited in the main galleries, but instead extends value to what is commonly considered a collateral space.

Disturbance is key, alongside a good dose of irony. The fact of being extremely visible, but also bodily present in passageways, is fundamental when trying to break down the institutional sectoralization of spaces. Much like Hassabi and Childs, in On False Tears and Outsourcing, presented in 2016 at the New Museum in New York, British artist Cally Spooner occupies the lobby of the institution with eight performers following a choreography shaped by contemporary pop music and eerie movements. The piece revels in contrasts, combining contact sports techniques and movements that create intimacy between the performers, all in a state of hyper-visibility resulting from being in a space that is both adjacent to the café and the entrance of the museum. Challenging the power of institutional architecture, Spooner condenses the unsettling play of Childs’s piece through the intimate approach of Hassabi, reclaiming the space of the lobby not just a place to pass through, but a space to linger.

The result of these experiments is a canvas, a toolkit for an institution rewriting itself, adapting new politics and new publics to a way of life in which communities of spectators transcend canon. Disturbance, irony, and uncanniness, combined with the bodies of the performers, produce new dialogues, new spaces, and, above all, an occasion to maintain the museum’s intent of investigating forward-looking practices while speaking to new audiences. The future of the institution, then, may not lie exclusively in its exhibition halls, but in the challenges produced by the friction between art and newly discovered environments: the lobbies, the stairs, the corridors, and all those unexpected spaces where art produces new meanings.

[1] For further reading, see Brian O’Doherty, “Inside the White Cube: Notes on the Gallery Space, Part I,” Artforum 14, no. 7 (March 1976): 24–30.