Stitching Time Together: In Conversation with Rose Marie Cromwell

Traveling through deserts, mountains, caves, and off-grid sites with her family, photographer Rose Marie Cromwell makes photographs that move between the intimate and the ancient, where bodies and landscapes are entangled, and time folds in and around itself. A Geological Survey, recently on view at EUQINOM Gallery in San Francisco, is Cromwell’s meditation on the landscapes and relationships that formed her, returning to the American West alongside her mother and daughter.

Cromwell’s photographs resist the inherited, masculine language of Western landscape photography and focus instead on an embodied, maternal approach to seeing. There are moments of bathing and resting, stillness and play, all echoing against ancient rock formations and fallen trees. In Cromwell’s hands, motherhood is subject and method. It is a way of understanding labor, vulnerability, and responsibility in a world shaped by extraction and loss.

Installed through silk, layered prints, a quilt, and sculptural arrangements, A Geological Survey invites viewers to move through the exhibition space slowly and with care, as one might move through land. In this interview, Cromwell reflects on returning home, photographing within her family, and re-learning how to see landscape through touch, inheritance, and time.

Samantha Jensen: I want to begin by asking you what it meant for you to make this body of work. What did it mean to come back home to the West?

Rose Marie Cromwell: I am grateful to have the chance to take my daughter to places that I spent a lot of time in while I was growing up. The Badlands and the Black Hills in South Dakota are not only geologically unique places, but they are also culturally and spiritually meaningful landscapes. To return to the landscapes that held a strong place in my psyche, and to be able to experience them with my daughter, feels very full-circle and has brought me some closure.

I also feel lucky to have figured out how to make work with my family. Involving my daughter in the creative process is two-fold: I am spending time with her, and I can involve her in something I love, which is image making. I was inspired by looking at Robert Frank’s method of making as somebody who did road trips, but as a man with a family. I wanted to see how I would move throughout space as a mom photographing with a family.

SJ: This work is really cyclical, referencing generations of women and the water cycle. The landscape is its own character that bodies are constantly in exchange with. What other themes are you exploring?

RMC: A big theme in this work is time and the timelessness of raising a child. Sometimes you feel like time is slipping through your hands. It’s been six years since I gave birth, and it feels like no time at all, yet there's like a fully formed human walking by. Having a child warped my sense of time in a way. And then you look at one life in context with the land. Those mountains were there when I was a child, and this rock has been around for millions of years. The time comparisons don’t even come close. There is a level of grounding I feel in this fleeting life when standing on a mountain.

For example, the quilt I have included in this exhibition is made up of three images. One image is just of the log, one is Simone lying on the log, and one is her sitting on the log. Talking about our relationship with nature has always been important to me because, in the history of male-dominated landscape photography, people have often been so separate from it. Those photographs make us feel like nature is something to awe at, a spectacle. But really, we are so reliant on and embedded in the landscape.

SJ: Your attention to specific Western sides feels deliberate, as if each location holds personal memory, but also carries longer, more troubled historical weight. I'm curious how you chose locations to photograph?

RMC: Personal narrative started me on this journey. I wanted to revisit places from my family roadtrips we took when I was a child. My stepfather was from Montana; he grew up in these really small, rural cowboy towns. He wasn’t indigenous, but he had a lot of interactions with indigenous people and spoke about their myths and relations with the land with a lot of reverence. He also spoke about how the land shaped a sense of identity at length. I went to places in South Dakota, Wyoming, and Montana that we went to as a family. Also, I was born in Sacramento, and my mother currently lives in the Bay Area. We have made some work trips in California and also Colorado, where my husband is from.

I chose locations for their off-the-grid establishments. As someone who has critiqued globalization in a lot of my work, I wanted to research sustainable living off the grid.

SJ: The images suggest a way of looking at our collective future and that of the land with maternal instincts. Were you thinking about cycles of motherhood and care while making this work?

RMC: Definitely, and this is why I started to involve my mother in the work. In my early 40s, I see the end of life in a clearer way, but also, having a child, I see the beginning of life in a clearer way. I am suddenly at the peak of this hill of life. We all do the best we can to mother, but there’s so much you can learn from your mother or from your child about how to re-mother yourself or to heal things with past generations. I found making work together to be a very healing and bonding experience for us. I get a lot from mothering, and I find caregiving of a child and an elderly person to be quite similar. Through this care, I am also working on myself as a child, too. This is really the definition of love, giving without expecting in return, and that most of the time in our lives manifests as parent-to-child love.

[My daughter and my mother] have a special bond. I didn’t really meet my mom’s mom because she died when I was pretty young, but my dad’s mom, I was close with. And I always felt like she was a portal to someplace else. I have dreams that her bedroom was this cosmic portal. I feel like that connection allows me to forgive my mother for whatever things I've held against her, as I’m sure my daughter will hold things against me, too.

SJ: That’s really beautiful. This show dissolves some of the boundaries between photography and sculpture, too. Can you tell me about the curation and installation choices for this exhibition?

RMC: I’ve always been interested in installing photography in ways that activate space and respond to the space available. We’ve put photography in a box where historically it needs to be a line on the wall, all in the same frames. In this exhibition, I printed this image of my daughter immersing herself in a hot spring on two large silk pieces. I love it because it becomes a fluid piece that moves—if you walk by, or the air conditioner is on, or there’s wind, it echoes the sense of water. Just like in sculpture, the medium helps tell the story. The silk is soft; there’s a feminine nature to it. I also made a photo inspired by my mother’s quilts and her mother’s quilts. I wanted to reference that medium as a storytelling device for women.

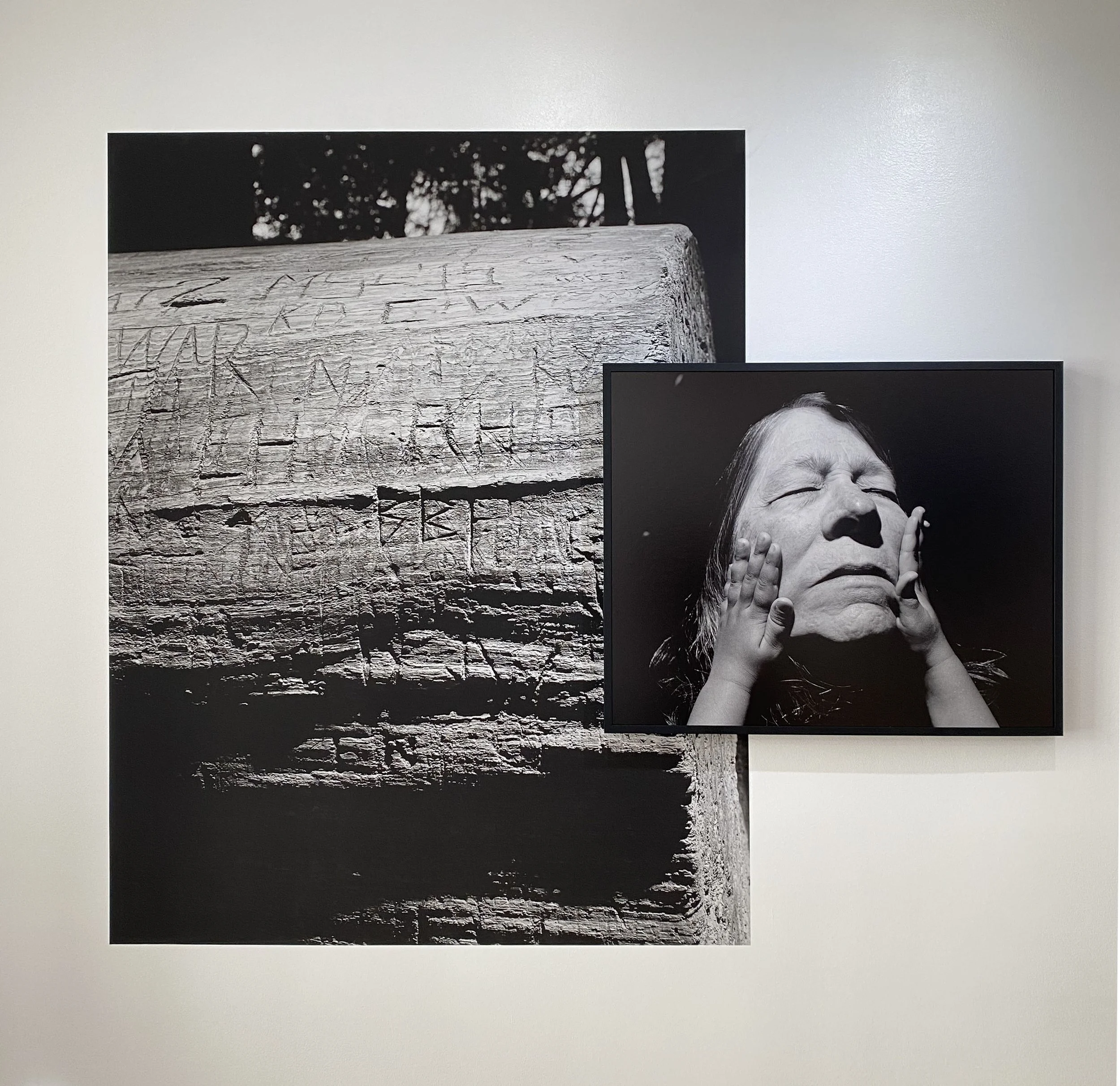

SJ: I really like the way you overlapped the close-up image of your mother and your daughter’s hands on her face, with the image of a fallen redwood tree.

RMC: That image is of a redwood fallen that people have etched their initials in. It is such human nature to want to outlive this redwood tree, you know? Perhaps people are marking their place in time, but, ironically, it is done through this destructive gesture. My daughter is pulling on my mother’s loose skin on her face. This juxtaposition is really about our innate desire to fight the way of time.

SJ: Did different choices go into showing A Geological Survey here versus exhibiting in Miami?

RMC: I was really excited to exhibit it here in the West because landscape photography was really born here, thanks to the survey photographer in the late 1800s. There are also some really established contemporary landscape artists working out of here today. It’s a more popular subject in the West than in Miami. I was excited to include some of the newer images as well, like The Field (2025). As my daughter gets older, she becomes more conscious of the image-making process. And maybe the images become a bit more performative.

The Cave (2025) is a new image, too. The image is symbolic of when I was giving birth to Simone on day two, my doula asked me, “What’s going on? Why are you holding back? What are you afraid of?” I was afraid of dying, as the pain was so intense. She told me I couldn’t be afraid of dying when giving birth, because you’re giving life. She told me I needed to go find my little soulmate. So I imagined myself going into a dark tunnel and going to find her. That visualization helped me give birth, going into a tunnel of the unknown.

That imagery really stuck with me. There’s a Lakota Sioux origin story concerning the Wind Caves, the Black Hills. Their ancestors came out of the ground out of a specific cave. I try to teach my daughter that these origin stories are important and can help us make meaning and give context for how people choose to live their lives. There are also many overlaps in these stories. A cave is a passageway, a birth canal, an entry and an exit, and a ripple in time.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Rose Marie Cromwell: A Geological Survey was on view at EUQINOM Gallery through January 30, 2026.