Martha Cooper on “Concrete Chronicles”

The Lower East Side occupies a near-mythic place in the collective imagination of art, music, and cultural history. Often conjured through the legacies of figures like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, this version of downtown New York, especially during the 1970s and 1980s, is frequently cast as gritty, rebellious, electric, and dangerous. What tends to disappear in these retellings, however, are the lived realities of the neighborhood: the families, children, immigrant communities, informal economies, and creative interventions that shaped daily life amid systemic neglect. [1-3]

During this time, photographers not only documented the emergence of graffiti writing, street art, and hip-hop culture, but also bore witness to neighborhoods surviving without adequate civic support. Martha Cooper is among the photographers whose images have come to define and preserve this history.

Her exhibition Concrete Chronicles, presented alongside Clayton Patterson at City Lore on East 1st Street, brings together decades of this work, tracing the intertwined histories of art, music, and everyday life on the Lower East Side. On view through February 1, 2026, the exhibition resists nostalgia in favor of something more complex: a portrait of creative survival, collective authorship, and cultural production from the ground up.

Eden Chinn spoke with Cooper about her early relationship to photography, her commitment to documenting local communities, the global afterlife of graffiti, and the realities of forging a career in a male-dominated field. What emerges is a practice rooted in capturing everyday moments and gestures, and the belief that what might otherwise disappear is worth holding onto.

Eden Chinn: You were exposed to photography from a young age, as your father owned a camera store. Did you realize growing up that being a photographer could be a career? How did that all start for you?

Martha Cooper: In fact, I didn’t. Maybe it crossed my mind in college, but I had no idea how to do it. Also, the college I went to, Grinnell College in Iowa, had no photography program. But when I graduated at 19, I wasn’t even thinking about a career and had no idea what I wanted to do. I took pictures in the Peace Corps, and I did graduate work in anthropology before getting a job at the Smithsonian and then at Yale as a curatorial assistant in anthropology. While I was there, I read about somebody who’d gotten an internship at National Geographic, and I thought to myself, “I want to be out there in the field taking pictures, not in the museum organizing artifacts.” So, I applied for that internship, and I got in using the pictures I took in the Peace Corps, and from that point, I was determined to pursue photography.

EC: What were the early pictures you had taken while you were in the Peace Corps like, and what was it about the experience that shifted your mindset about photography?

MC: They were very good as a starting point, but they were just whatever I saw. I had no particular picture story. I knew nothing about photojournalism. But then my mother came to visit me, and she brought me a Nikon, which did not have interchangeable lenses. I didn’t get the interchangeable lenses until I went to that internship. Before that, I was just taking ordinary pictures.

EC: When you started documenting street art, graffiti, and Lower East Side culture, did you realize how special the moment was while you were capturing it?

MC: I always thought that I was capturing things that would disappear. I worked for the New York Post for three years and got a sense of “the special”—the journalism idea of “We have it and you don’t.” So, I was getting an exclusive on the graffiti world, but I never thought it would go worldwide. I thought it was something specific to New York City at that particular time. It still surprises me—not just street art, but [the prevalence of] graffiti writing. I’ve gone to the Congo, where they’re doing New York-style graffiti. I went to Mongolia and Réunion Island, and I saw New York-style graffiti. And I kind of thought graffiti would have disappeared after [the New York City government] started cracking down on [graffiti on] the trains, yet it’s spread to countries like Scandinavia, where things are neat and tidy.

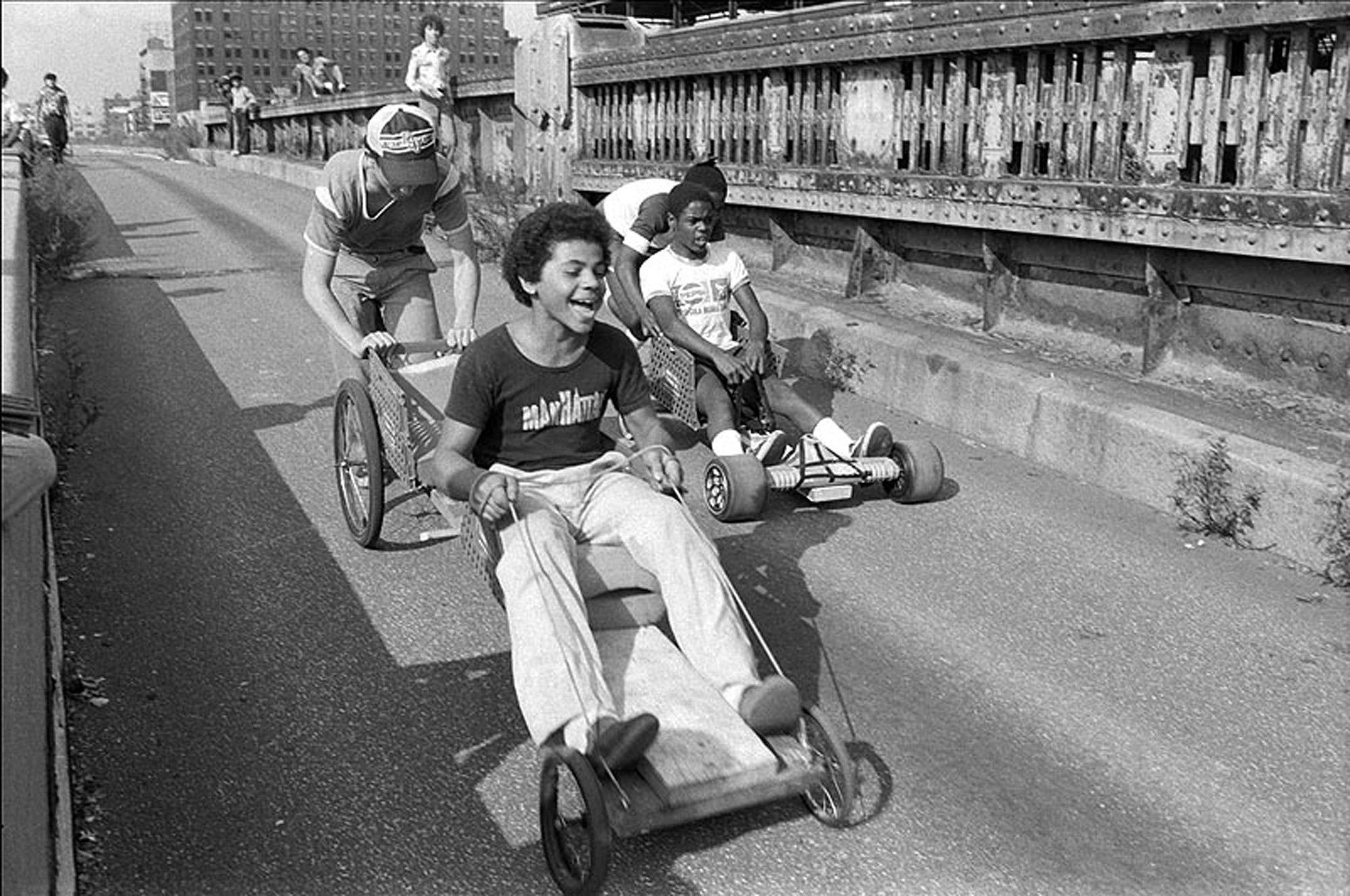

EC: In terms of the Street Play (1978–1979) photos of children playing on the Lower East Side in the 1970s, how did that project come to be?

MC: The NY Post was on the Lower East Side, and I would drive through the neighborhood every day. We had radios in our cars, and for an assignment, they’d radio us. So I was driving around, and there were all these abandoned buildings and kids playing. One day, I saw a kid with a go-kart and decided to shoot that for my personal practice, instead of for my job, and this was 1979. I was at the Post from ’77 to ’80. ’79 was when I mostly did Street Play. But now I’m doing Street Play in Laos, so I’m kind of expanding it worldwide.

EC: What was it about what you were observing on the Lower East Side, with the children specifically, that drew you in?

MC: They were being so creative, and the adults weren’t watching. I had been encouraged to be creative as a kid, and these kids were building houses from the rubble; they just had a lot of freedom.

EC: What story do you feel like your photographs tell about the Lower East Side, and how has the neighborhood changed?

MC: People were actually afraid to go into some of these neighborhoods. There were vast open lots, abandoned buildings, and some that weren’t even boarded up. The lots where I was photographing the children were full of rubble from burned-down buildings, or ones that were neglected and fell down. On the other hand, there were many immigrants and families. Most of the kids I met were allowed to play freely because their families were busy working. Now, I think it would be rare to see kids in a vacant lot, building a little house out of found materials.

EC: I’m also curious about the photos in the exhibition Concrete Chronicles at City Lore that capture historical moments in relation to art and the Lower East Side.

MC: I think it’s important to note that the Lower East Side was not considered an arts neighborhood. When Patti Astor opened up the Fun Gallery in 1981, that was almost a radical thing because there were no other galleries in the neighborhood. But people gravitated to that and turned it into an offbeat arts area. Now obviously, here we are, and various other galleries followed.

EC: Thinking about art and photography today in relation to technological advancements, how has increased accessibility to photography impacted your practice?

MC: Well, photography has certainly lost its exclusivity since everybody can do it and there are so many really good photographers out there. I used to feel more special—I had knowledge in terms of my technological ability with photography that other people didn’t have. But I don’t feel that anymore. Digital is so much easier than film, and you can just take out your phone and take a really good picture.

EC: With this increased access, how do you contend with the overwhelming quantity of images being produced today, and what do you think makes a good photo worth capturing?

MC: Interesting subject matter. For me, I’m not just into patterns and shadows. I want to see something in that photo that makes me more curious about the photo’s original context. Then it has to be framed well and in focus. I want it to be technically good but also interesting. I don’t like photos that are too artsy, where the photographers are trying so hard to make things seem interesting. But sometimes even simple snapshots where somebody hasn’t tried that hard, I find really interesting. I like all the little details of a photo.

EC: Looking back on your success, how does it feel knowing you broke into a male-dominated field as a photographer and trailblazer for so many future women photographers? For example, you were the first ever woman editor at the NY Post.

MC: For whatever reason, people thought photography was a man’s job, probably because it was about operating equipment. However, George Eastman, who founded Kodak, initially advertised cameras for women because they were the ones who were more interested in preserving and documenting special moments with their families. I actually did a book collection called Kodak Girl, which was published in Germany; it is a 350-page book exploring this “Kodak Girl” campaign, which focused on advertising to women. I used to go to ephemera shows and photo shows, and then eBay came along. There’s a range of ephemera I’ve found. There’s a whole series of Barbie as a photographer and Barbie cameras. Barbie had a zoom lens and a darkroom and was a very accomplished photographer.

I didn’t have a female gaze. I steered away from feminist subject matter even though I am a feminist. I felt that my being out there doing it was enough.

Even Cooper’s current projects—whether it is documenting children’s street play across continents or turning her lens toward more unexpected subjects—extend the same attentiveness to everyday worlds often dismissed as peripheral. What stands out in speaking with Cooper is not a retrospective impulse, but a sustained way of working that has barely changed, even as the conditions around it have. She does not frame her photographs as interventions, nor does she claim authorship over the cultures she documented. Instead, her practice emerges from proximity: being present long enough for access to feel ordinary, and for people to act like themselves rather than subjects.

Concrete Chronicles resists flattening by placing art, play, and survival side by side, refusing to isolate graffiti or downtown icons from the neighborhood life that surrounded them. The exhibition makes clear that what we now read as cultural history was once simply daily life, unfolding without guarantees of preservation or recognition. It seems that for Cooper, photography was never about capturing a scene at its peak, but about staying with it long enough to understand what might change or become lost. That patience, which was rare then and is even rarer now, may be the most radical throughline in her work.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.

Concrete Chronicles is on view at City Lore Gallery (56 E 1st Street, New York) from October 21st, 2025 to February 1st, 2026.

References:

[1] Rose, Brian. “Twenty-Three Years Later: Two Moments on New York’s Lower East Side.” Places 16, no. 1 (2004). PDF accessed via eScholarship.

[2] Rinesty Rusli, Improve, Don’t Move: Sweat Equity Homesteading in New York City During the Fiscal Crisis of the 1970s (Senior Thesis, Barnard College, Columbia University, Spring 2019). PDF accessed via Barnard.edu.

[3] Reclaiming Space: Squats, Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space. Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space (MoRUS). Accessed online.