An Image Erased: In Conversation with Ken Gonzales-Day

Ken Gonzales-Day is a Los Angeles-based artist whose interdisciplinary practice spans photography, writing, research, installation, and photomontage. His works navigate the social construction of race and queerness, as well as artistic and institutional entanglements in legacies of colonialism and white supremacist violence. He is the Fletcher Jones Endowed Chair in Art at Scripps College and is represented by Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Spencer Klink: I’d like to start by asking about the title for your recent show, History’s “Nevermade”, at USC’s Fisher Museum. When and how did you conceptualize the idea of the “nevermade”?

Ken Gonzales-Day: The exhibition’s title was created by the curator, Amelia Jones. She was inspired by my project Bone-Grass Boy, in which I created a fictional book as a “nevermade.” The concept drew from Duchamp’s readymade—a recontextualization of the meaning of a historic object within an artistic framework. As a white cis European male, he could pull from his cultural references easily.

In my case, as a queer Latino of mixed ancestry from the Southwest, our histories have largely been erased or are currently being erased. Right now, in the United States, LGBTQ+ histories are being removed from institutional memory, and books are being banned. The idea of the “nevermade” was an attempt to make a visual representation of the historical erasure that people with overlapping identities like myself have faced.

SK: I love the Bone-Grass Boy Project, and I was drawn to your construction of a narrative through text and image. How do you view your role as a photographer in mediating history?

KG: I was thinking about the role of photography in representing otherness. The work was informed by other artists who used their own bodies to represent their histories, like Laura Aguilar and David Wojnarowicz. I wanted to tell a story that has never been told and that was specific to my ancestry.

In the exhibition display, there is what looks like a book that has been cut apart, photographed, and placed in a series of vitrines. In fact, there is no real book, and if you look very closely at the images and text, you realize that all of the characters are me. It’s a spoof of historical narrative.

A lot of people do not look very closely, so the book often takes the place of actual history. I used this strategy to make space for the “nevermade.” The exhibition also includes images from the original text, which are blown up and put on the wall as traditional color photographs, and three-dimensional elements.

SK: The digital format of the text is very interesting. Did the project start as a physical book?

KG: My intention was to create digital images that look like a real book. The project started back in 1994 with Photoshop 3, when there were no digital cameras, so it was quite challenging at the time.

I was a very young artist and did not often get opportunities to show my work. In a group exhibition, a young queer Latinx artist would be lucky to show one or two pieces in a group show, with maybe three or five feet of wall space. I wanted to create a project that I knew would never be represented completely in an exhibition space.

Initially, I would show one chapter or section and construct a larger narrative through different group shows. Even now, the whole project has never been shown. Quite a lot was displayed in 2017 as part of the Getty’s [Pacific Standard Time: Los Angeles/Latin America] initiative, when my gallery, Luis de Jesus, allowed me to reinstall as many elements as I could.

SK: This idea of the “nevermade” is a correction of historical erasure, which brings to mind your series Erased Lynching. Here, erasure seems to become a strategy that addresses legacies of atrocity.

KG: The Erased Lynchings series is a project that developed a few years after Bone-Grass Boy. I started looking into the history of lynching nationwide and the role of Latinos in that history. This resulted in the publication of my first monograph, Lynching in the West: 1850–1935, which documents over 350 cases of lynching in California, of which the largest single ethnic group is Latinos.

I began wondering why nobody had written about the racial killing of Latinos in California, Texas, and across the southwest. The strategy of erasure here was to ask why this history was erased, and why violence against Latinos has been ignored.

This is still going on today, as people are disappearing from the streets of Los Angeles, hunted and stalked at Home Depots or other places. Yet the idea of racial terror somehow doesn’t apply to brown bodies. I wanted to find a way to share that through my art.

For the images in the series, each originally depicts a historic lynching. The photographs were initially sent all over the country as postcards. Eventually, my project evolved to include examples of many different states to create a larger picture of these acts of collective violence. Each image is reproduced at a scale to look like the original postcard.

SK: Shifting to your work for the Getty’s Queer Lens show, could you please share more about your idea of the “queer imaginary”?

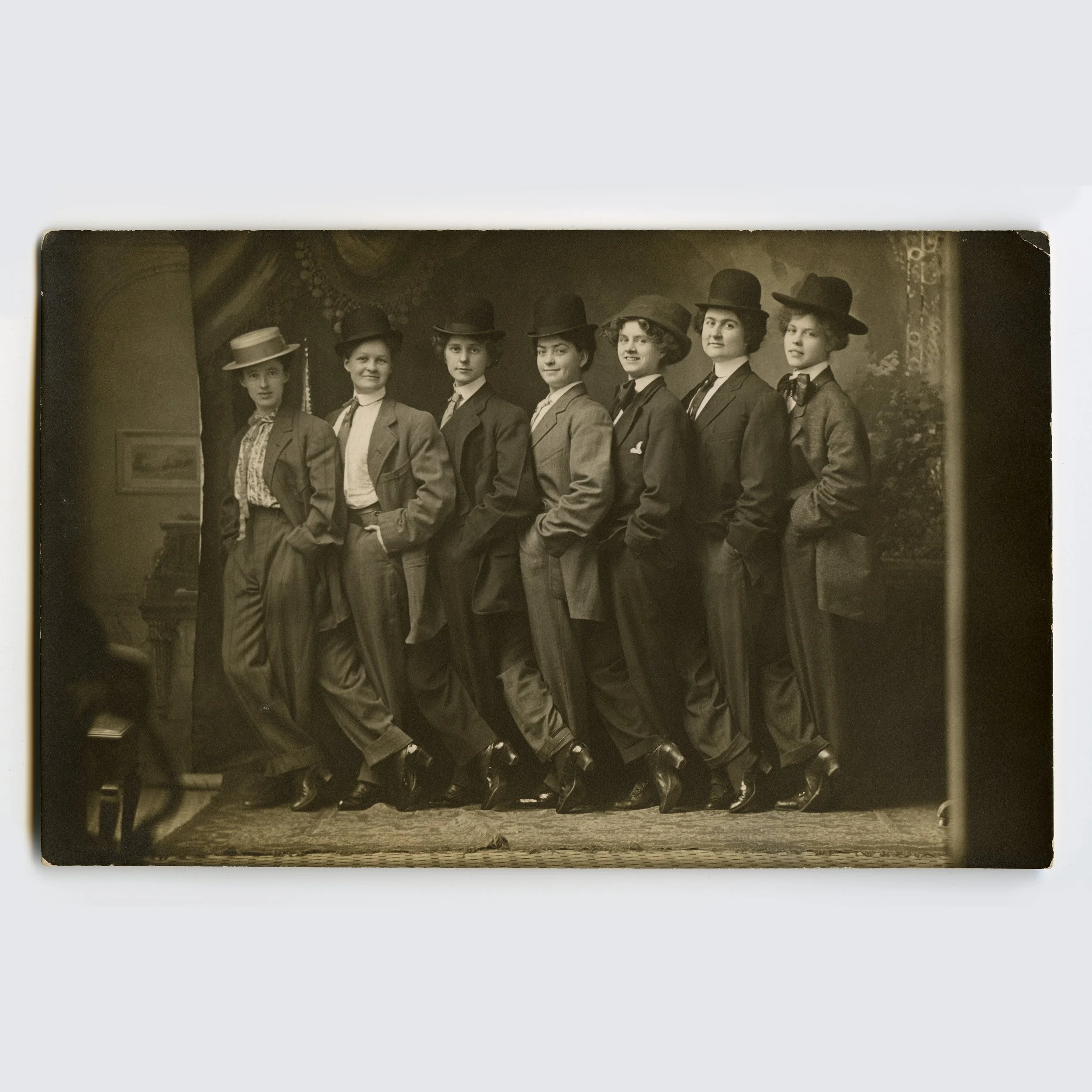

KG: The exhibition looks at the entire history of photography, and I was invited to address the period from 1901 to 1945. I focused on the development of vernacular photography, in which new camera technologies became very cheap and available to everybody.

Suddenly, queer people are finding cameras just like everybody else, and they’re photographing themselves and each other. Against centuries of erasure and absence, we now have images appearing of queer people. I started wondering how these individuals conceptualized themselves as they created these images.

That’s where I borrowed from a number of scholars writing about the racial imaginary to come up with the queer imaginary. The racial imaginary is the notion that all of the cultural representations surrounding race live within our conscious and unconscious minds. I believe that there is an equivalent attitude about queerness.

How does a person continue to live through their day with no other connection to another queer person? The only way is through the imaginary, by envisioning that one is not alone in the world but rather part of a community. These images become an expression of that.

So the Getty show not only touches on the past, but also on how we use these images in the present. How do they empower us? How can we take their legacies and carry them forward? How can we use them to contribute to and create visibility?

Ken Gonzales-Day: History’s “Nevermade” is on view at USC’s Fisher Museum from August 19, 2025 through March 26, 2026.

Queer Lens: A History of Photography was on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum from June 17, 2025 through September 28, 2025. Gonzales-Day’s essay, “Photography and the Queer Imaginary, 1901–1945,” can be read in the exhibition publication.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.