In Conversation with Ceirra Evans

Among the colloquialisms of Kentuckians is the saying: “Lord willing and the creek don’t rise.” Comparable to “With any luck” or “Insha’Allah,” the phrase speaks to hope for the future, acknowledging that a higher power—as well as nature’s collaboration—is essential to success. This is no coincidence; in a farming state increasingly faced with tornadoes, flooding, and human-inflicted environmental malaises, the changing weather is on people’s minds much more than an outsider might assume.

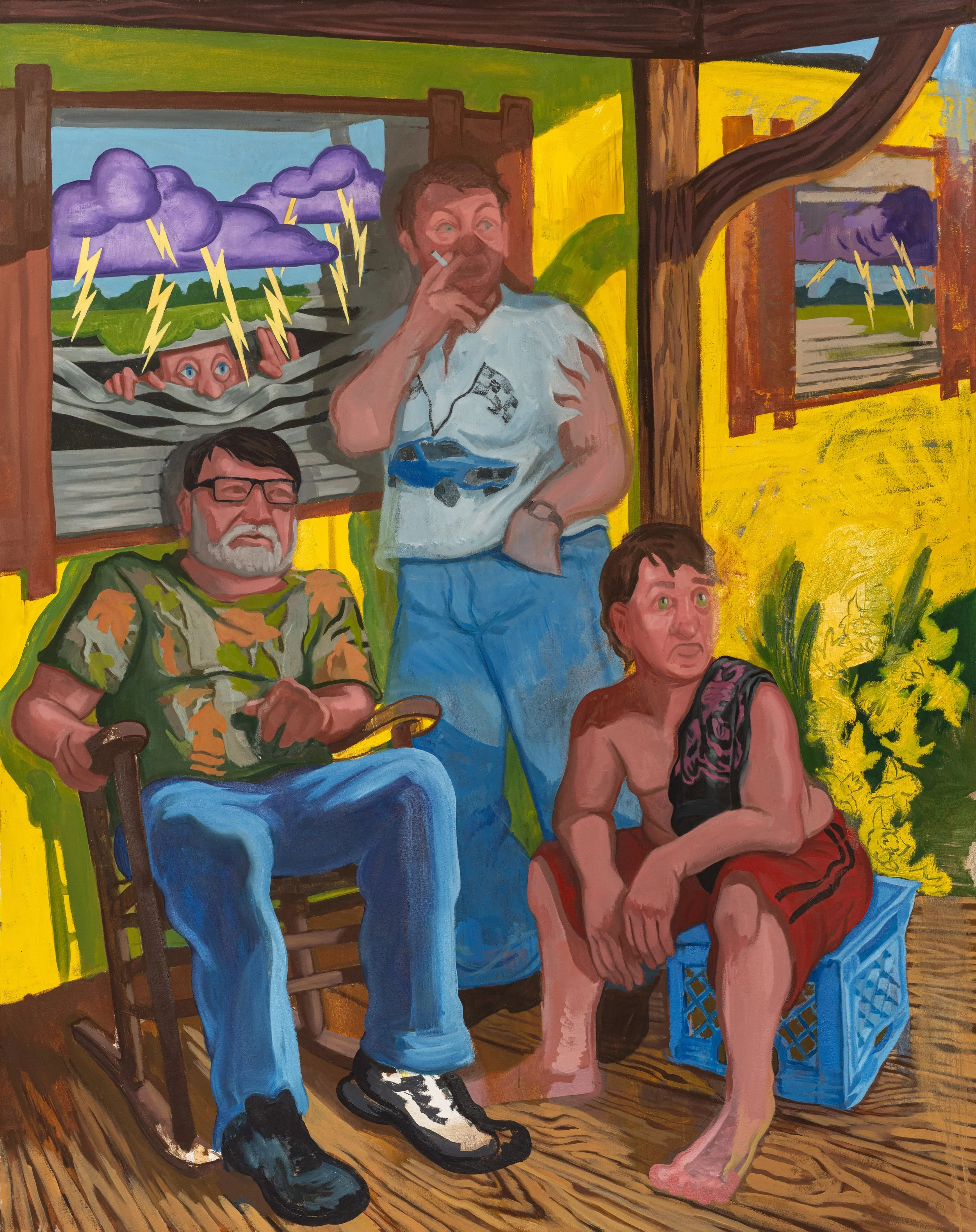

Ceirra Evans’s life and work are a primary source for this nuanced reality. Having exhibited near and far, from Virginia Tech’s Perspective Gallery in Blacksburg, Virginia, to Galerie Géraldine Banier (now Perspective Galerie) in Paris, France, Evans once again presents a body of work in her home state at Lexington’s Institute 193. Specific, witty, and symbolic, the paintings of Come Rain or Shine address the four seasons through the eyes of Evan’s family and community—as Belle Townsend states in the exhibition text, “Evans paints with love, but never with illusion.”

In this conversation, we discuss the formative experiences that built this body of work, how Evans turned a difficult hand into opportunity, and the importance of leaning in when faced with something we don’t quite understand.

Maria Owen: I want to begin by talking about your experience in Kentucky, for those who are unfamiliar with what daily life might look like there.

Ceirra Evans: I grew up in Northeastern Kentucky with a single mother. And I grew up on a creek that flooded all the time. It was very fertile ground, and so we had a nice little garden that we tended to every summer. It was all of us always outside, at least in the summer, making the garden in front of the house, cutting the grass. And sitting—doing a lot of sitting on the porch. That was always such a big summer activity. You can see that reflected in the show.

A lot of that’s changed, though, considering I was living in Louisville when I made these paintings. When it comes to my practice, one of my biggest focuses has been trying to notice more of what is happening within the seasons. Now, part of my process is watching how those seasons change throughout the year. I just moved to Frankfort, particularly for my work, so that I could get back to that slower lifestyle.

MO: What brought you to Louisville—the largest city in the state—from life in the countryside?

CE: My senior year of high school was a pretty tumultuous one, and at that point, I just wanted to get away. I only applied to out-of-state schools, and I got accepted into some of those bigger schools, but the one that I really wanted to get into was RISD. And when I got in, it was like, “Holy shit, I got into the RISD painting program, I gotta go.”

Two weeks before I planned to go, the financial offices called and said that there was simply no way. So it, you know, fucking sucked at the time, and I was heartbroken.

So I stayed in Louisville, and for the first two years of college, I tried to just get out. And then I think I finally realized that if I can’t get out, then I have to do something with the situation I’m in. I ended up switching my degree from Painting to Liberal Studies so that I could become a better orator for my work. I already had the obsession, the want to paint, the want to tell stories, but it was exactly what we’re doing right now that I needed to learn. To be in the art world, as good a painter as you are, you’ve got to be a good talker.

MO: That’s such great advice for rising artists. Often there's a resentment towards talking about one’s work, because so often artists make the work so that they don’t have to explain in words.

CE: For sure, and I’ve thought about that the more I’ve read about painters. I recommended two books for the Institute 193 Bookshop, one being Philip Guston’s I Paint What I Want to See. We can talk all day about what Guston paints, but I think the process of how he paints is something that’s always stuck with me. You can tell from the way he talks about it that he really understands his process. That’s something that I come back to every time I start a new show, and even more so with Come Rain or Shine, because I’ve had more time to make this work than any other show. I really think about that process with each painting, asking, “What decisions am I putting forward?” I want to be able to talk about that process whenever it comes time to do that.

MO: Can you tell me more about that process, particularly for this show?

CE: As I get older and mature more, I want to take it a lot slower. And so with this show, I decided to only do eight larger paintings. Those were my two main challenges this time—objectively bigger paintings and keeping it to a very small set. Before I started, I was studying how people react to changing weather. I was having a lot of conversations with my friends in Southeastern Kentucky, and how they feel whenever they hear that crack in the sky.

The great thing about having only eight works was that I could do two paintings per season. It allowed me to get very specific. I was talking to Dianna Settles about this at my artist talk, and we were thinking about Bruegel’s season work. You look at those paintings, and there are thousands of stories in them. When I start to paint, I think, “Let me make this great big story that hits all these points.” The limitation allowed me to close in more and more specifically on the people I'm highlighting, who they are, and the context that they’re in.

Another thing that changed a lot with this process was that previously, I would just start directly on the canvas. This time around, it was a lot more of: “Let’s sit down at the desk. Let’s sketch. Let’s really think about how you want certain forms.” I was thinking about the forms of the roses in Coming up Roses (2025) and how I could carry them throughout the whole show. The yellow trailer appears throughout. I was thinking about how to make people feel like they’re entering this community.

MO: Tell me about the figures. Are these people you know? What do you feel is essential to document?

CE: Well, Coming up Roses is a painting of my mother. I think what’s more important for me is that these figures are close to me. My mother is also represented in Fixin’ to Rain (2025), alongside my grandfather, who’s sitting in the chair. My brother and my partner are in other paintings. I try to use people who are closer to me because it allows a little bit more freedom to be more cartoonish. And these are the people who are living these experiences.

MO: These paintings examine those cultural questions, as well as changes in climate. How does change play a role in these works beyond the more direct seasonal imagery?

CE: In recent years, whenever we talk about Kentucky, we also talk about climate change and extreme weather. Like I said, growing up, I lived right on a creek which would flood up to the porch. That was just a regular thing. And there’s always been this sort of sublime connection to weather for Appalachian people, just because we do get so many damn changes within one day. We see that from the historic thousand-year floods within Eastern Kentucky, and with these tornadoes in Western Kentucky, and now all the way into Somerset.

I don't think people understand that, unless you have friends in Eastern Kentucky, unless you’ve grown up with this survivalist instinct your entire life, you don't understand how crippling it can be for those disasters to take over daily life. People are still trying to find a place to live since not even the last flood, but the one before it.

I knew that in painting these places, I had to be very sensitive to that sublime nature that comes with the weather, especially within Kentucky, where we obviously do have reverence for it. There are times that we sit on the porch and watch the storm roll in—I know a lot of people who would claim that experience as church. That’s prayer for many. But what also comes with that is the reality that it could become a big fucking storm out of nowhere and rip through. I try to find that line, to be honest about the mundane changes, not highlighting the extreme.

MO: And we're not seeing anything explicitly violent in these images, more moments of anticipation.

CE: For sure, and it’s all in the expression. It’s hard to paint that emotion that I think we all feel. The faces are saying, “I love this place, but it’s gonna keep slipping away.” I want to consider what kind of stories we’re going to tell, and what is going to outlive us. A part of climate change, and something I've tried to talk about a lot—even in work that’s not about that—is that nature is going to reclaim us in spite of ourselves.

From a very political standpoint, we should be fighting and making sure that we are the ones who take care of this land. We should be raising hell at our politicians whenever there’s a bill that allows people to put sludge into our waterways—it’s like, why the fuck would we even consider that sort of thing? We can’t see the end, or even fathom what that would be.

MO: Perhaps we could talk about the relationship between nature and queerness, and how these things are sometimes disconnected or muddied in rural settings? How do these elements fit together in your work?

CE: There’s this reality that nature and queerness bisect, that they live in harmony. In Spite of Ourselves (2025) highlights this specifically, being a depiction of me and my partner lying down in the field. We're just having a regular little date. There’s this imagery in the sky that I directly pulled from a Thomas Hart Benton painting, trying to pull a bull by the horns. I’ve always loved that motion, and I think that's such a direct way of stopping something that is so forceful and treacherous to deal with. These clouds pull this fossil fuel bull out of the sky, there are these direct attacks to our air and health—we live in a capitalist society. Yet we try to live in spite of that. It’s a romantic painting: two people who grew up in different parts of rural Kentucky, and how beautiful it is that we have found each other.

There is a direct question of queerness in the South. My queerness really started from me being a little country kid. When I was a little girl, I carried around a little satchel with me that had shotgun shells, turkey spurs, duck calls, all this stuff. I was always shooting cans, doing those more “boyish” things that are associated with nature. I do love being a part of nature. We can’t forget where we came from. I think that everybody in Kentucky, whether a young queer person or not, has had a connection with nature that allowed greater appreciation for life.

MO: What do you hope viewers and readers will take away from this exhibition?

CE: Whenever you're coming into these works, if you don't understand this context, you might not understand why these figures are feeling this way. As the painter painting these people who I know are misjudged, I’d like people to ask, “Why is it I don’t understand that? What is the part of this that I do not get?”

I’d also like to highlight Eastern Kentucky Mutual Aid. They’re doing a lot of really awesome things and putting direct money and resources in the hands of folks who need them.

There's a philosophy that I love that’s been coming up in conversation a lot—it says there are little Appalachia’s everywhere, and every community and culture is made up of that same survival instinct. That's what allows us to have such appreciation for where we’re at, what we do, and how we move within our spaces. Appalachia is not void of rhythm. It has amazing, creative individuals who are putting their best foot forward—just trying to make sure the people around them have what they need to keep walking too.

Ceirra Evans: Come Rain or Shine was on view at Institute 193, KY, from June 6 through July 19, 2025.