It’s the End of the World and I’m Unwell

Something else must be certain besides death and taxes. Stockholm-based artists Goldin+Senneby started their collaborative career playing conceptual games with linguistic slippages around tax shelters. Lecture performances and a sublime ghost-written novel about offshore banking gave way to sober meditations on illness and mortality when Jakob Senneby was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis. They pivoted, shifting their ambit to sick bodies slotted into healthcare systems driven by financial incentives, sized up, and strip-mined for value. This is called “extractive abandonment” by Beatrice Adler-Bolton and Artie Vierkant, whose 2022 book Health Communism is cited in the exhibition brochure for Goldin+Senneby’s current exhibition, Flare-Up at the MIT List Visual Arts Center. Flare-Up begins at that moment in Goldin+Senneby’s creative partnership. It follows them further through works holding a body’s immune system metaphorically and solidaristically parallel to larger existential questions about climate apocalypse. They propose kinship between personal health and the overheating, overcooling earth we live on together.

A docent outside MIT’s galleries instructs visitors to keep their distance from Flare-Up’s delicate centerpiece, Resin Pond (2025), a sprawling orange spill of pine resin. Entering the gallery, a sign partially blocking egress warns of “an extremely fragile floor work.” Wall text pleads for caution. Goldin+Senneby relate this deluge of resin—a hardening substance trees excrete when harmed as a protective seal promoting healing—to the rigid autoimmune overreaction of MS. If resin’s goal is protection, however, this floor piece is brittle armor. Despite the signage (and highly strung attendants hovering around the modestly sized gallery, often outnumbering visitors), fissures have formed in Resin Pond. They’re unexpectedly poignant: most seem less the product of careless viewers than the dense material collapsing under its own weight, suggesting a combative body warring with itself.

A collaboration, After Landscape (2024–), with art conservator Fernando Caceres, exhibits empty protective “climate frames” that formerly held landscape paintings attacked in actions by activist groups like Just Stop Oil. Caceres carefully reconstructs residues of thrown soup, glue, paint, and dye on the frames’ glass. While this review refuses to relitigate arguments about soup on paintings, Caceres’s work offers a dialectical formulation: “Landscape” as a painting genre derived from the physical landscape, whose subsequent protection by archival techniques has become a platform upon which activist agitation in support of environmental conservation might splatter and stick, like ab-ex painting gestures.

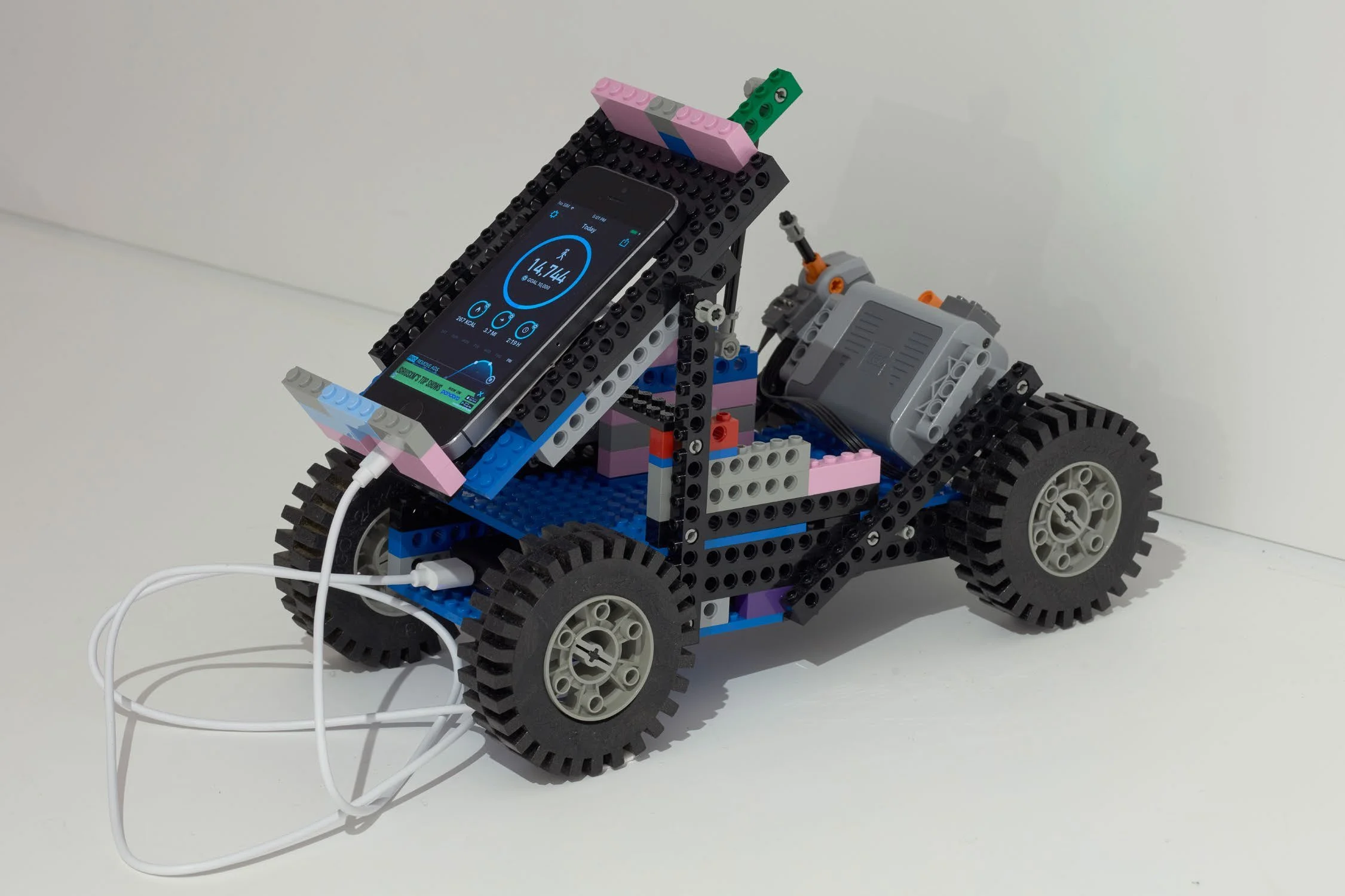

The earliest works on view, Lego Pedometer Cheating Machines (2019), are made of the titular toy blocks constructed using instructions sourced from online DIY patient forums. These little wheeled devices rock iPhones back and forth trying to fool their pedometers to circumvent insurers’ means-testing hoops to earn coverage. Health data activity goal barriers like these are polite eugenics, replacing skull measurements with step counting. Some of the machines succeed at their job admirably. During my visit, two were racking up thousands of steps while one sat motionless at 0. Another bounced vainly as its counter remained in stasis, and another unmoving one held a phone with a powered down screen. They’re easy to personify—they are, after all, simulating bodies.

The machines appear throughout Flare-Up, proposing a cohesive throughline to the presentation that their eager wiggling can’t quite substantiate. As with After Landscape, other bodies of work here (Swallowimage [2025], and Starfish and Citrus Thorn [2021]) trade in dusty, heavy-handed museological materials. The buoyant little cars don’t. Their subversion isn’t diminished by resourceful pluckiness, but it makes them outliers rather than unifiers.

Swallowimage, a more recent body of work, is technically the eldest. The initial gesture of unstretching and re-stretching canvases from the 17th through 19th centuries is an obtuse one, described as “literally turning them inside out,” which strains the word “literally” in an exhibition attended by otherwise exacting language. Hung from the wall by their edges, making both “back” and “front” visible, it’s not even precisely a reversal; it’s more like lateral rotations. Pedantry aside, the artists’ following operation on the paintings, injecting them with a parasitic fungus, transgresses the works’ sanctity more terminally than hurled soup or paint. Give those others fresh climate frames, and they’re ready to re-enter the canon, but these paintings are beyond restoration, moldering anecdotes in Goldin+Senneby’s oeuvre.

Maybe it’s the plus sign fusing Goldin+Senneby’s names, but climate activists emphasizing their cause’s urgency using art brings Martin Creed’s text piece Work No. 300 (2003) to mind. “The whole world + the work = the whole world.” When you subtract the whole world from the equation’s sum, the work disappears, too. Connective solidarities amongst ourselves and with the other moving parts that inhabit our environment are necessary if we want to go on savoring these artworks and people that fill the planet. Goldin+Senneby’s partnership frequently exemplifies this attitude, as they highlight systemic forces hindering a better world. Like it or not, we’re in this with them.

Goldin+Senneby: Flare-Up is on view at MIT List Visual Arts Center from October 24, 2025 through March 15, 2026.