Diagrams, Architecture, and State Power with Nick Angelo

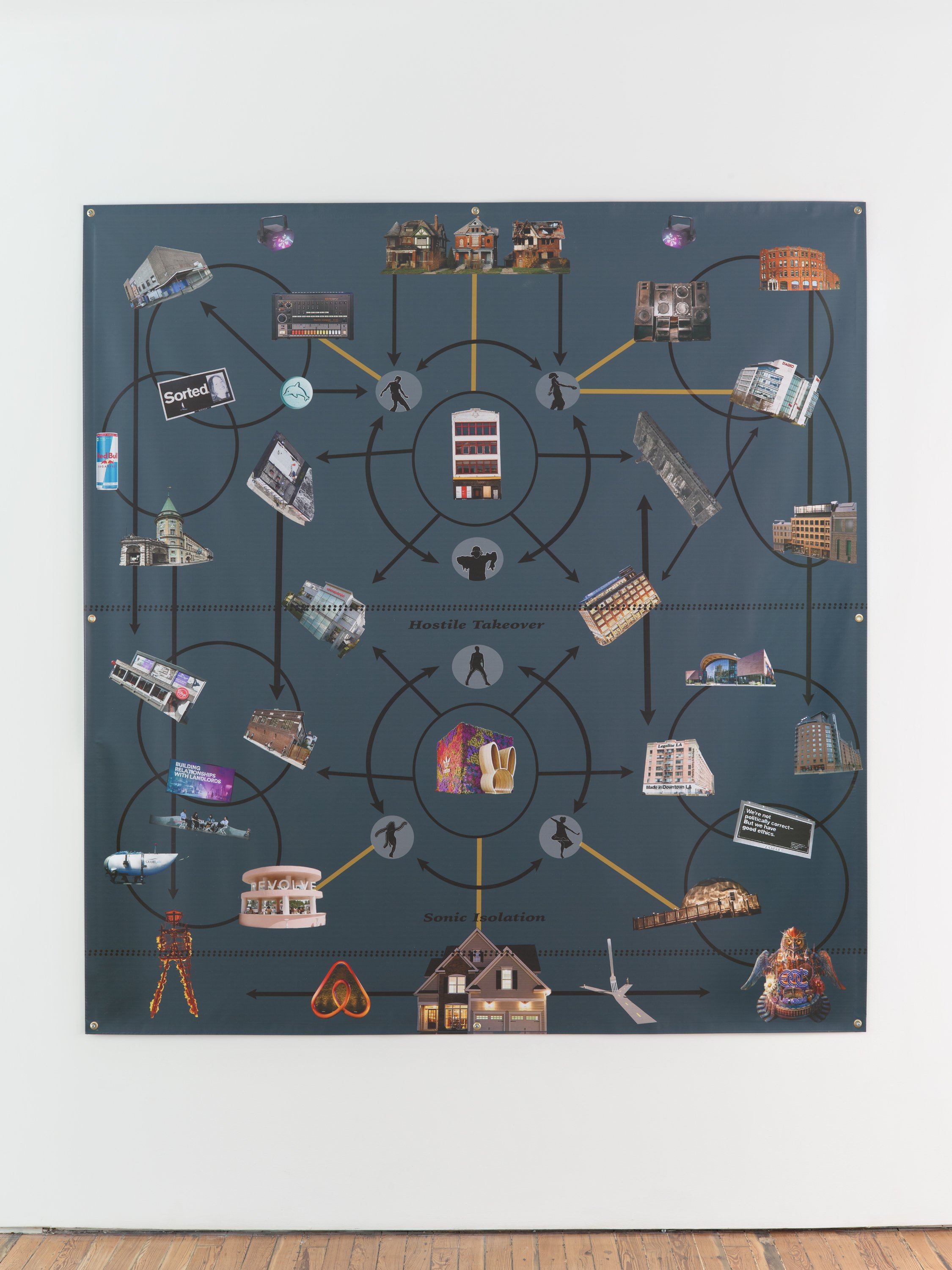

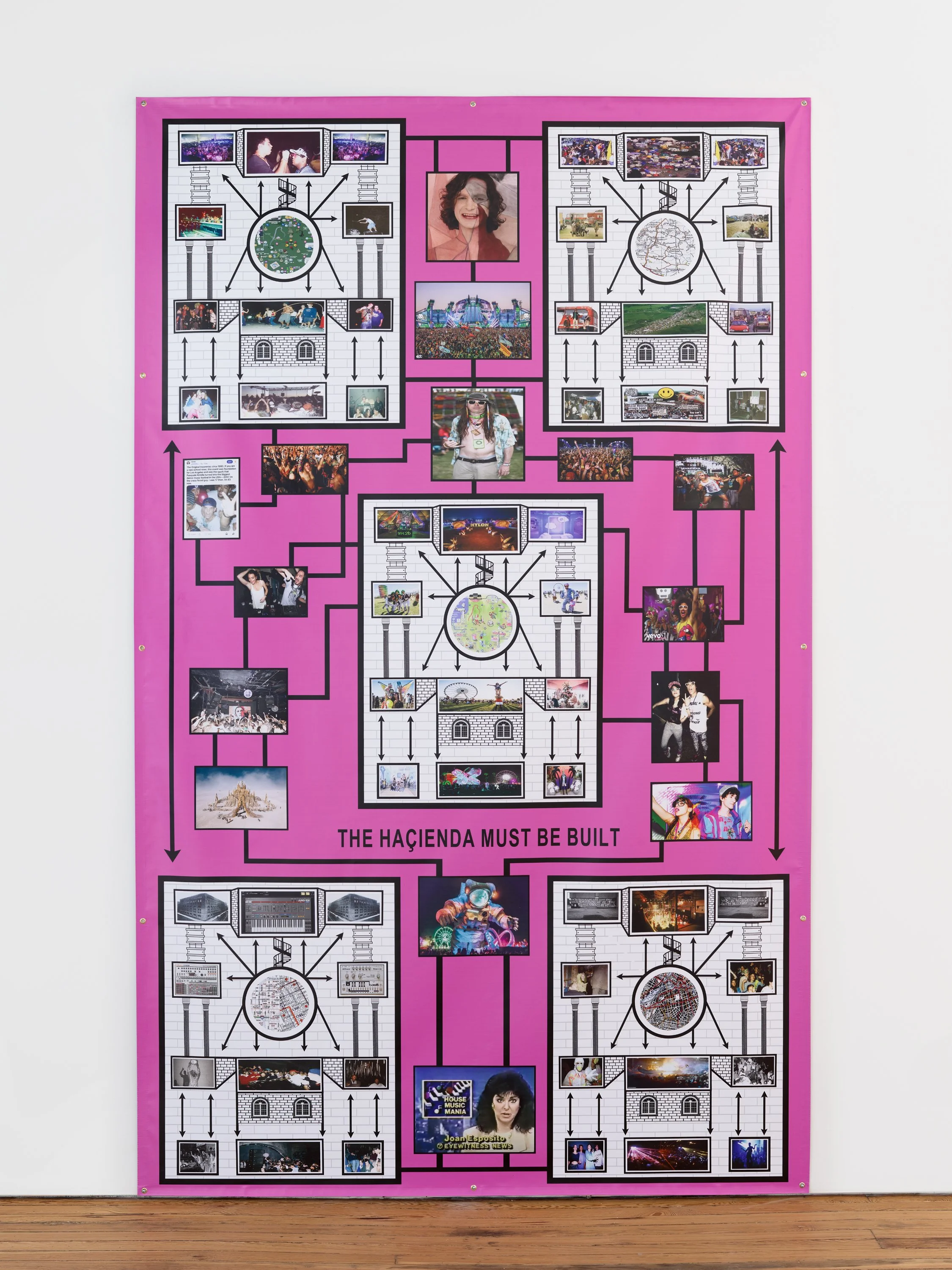

Nick Angelo is a Los Angeles-based artist whose work spans painting, sculpture, and installation. In September, he closed his first solo show in New York City, Edifice at Sebastian Gladstone—a series of diagrams on five vinyl banners. The diagram is well-trodden territory in contemporary art dealing with conspiratorial aesthetics (such as Mark Lombardi and Suzanne Treister) just as much as up-and-up political critique (such as Hans Haacke and Stephen Willats). This tendency, to visually map symbols and relationships, makes more sense than ever in an age where power is increasingly abstract and information is increasingly overwhelming. In Angelo’s work, the specificity of physical structures and spatial environments breathes new life into this tradition, in this case using found images to create a loose taxonomy of how space and capital are intertwined, from the United Nations to the rave.

The two of us discussed how the concerns and approaches of his practice have developed over time, the influences of harm reduction and architectural theory on his thinking, and how he sees himself fitting into lineages of conceptual art and informational design.

Ben Lipkin: Should we start by talking about what’s going on in the paintings behind you?

Nick Angelo: This is a series of paintings that I made all during the pandemic. Actually, they really kind of set the framework for Edifice, for the exhibition. In terms of having a linear, consolidated map or diagram that one is meant to understand, that’s never necessarily a part of the work, or a part of my practice. There are definitely theoretical, conceptually-based backdrops to the work in each painting. But for the most part, a lot of the diagrams are nonsensical, just because I really wanted to keep them contemporary with the way that my subjectivity and my brain processes and thinks about information and connections between certain entities. I feel like we're at a point where culture has become so overloaded with information that you can make a connection between any two signifiers, any two entities.

One thing that all of these works have in common is that the Purdue Pharmaceutical Headquarters appears in every single one of them. I guess the anchor to all of them is the opioid epidemic, and then thinking about the institutions where the opioid epidemic was kind of planted and where it was kind of manufactured, and then moving outwards from there, but at the same time like it also includes casinos. It includes art galleries. It includes art institutions. It includes gun shops. It includes methadone clinics and churches. It includes replicas of artworks, rundown houses, and it includes prisons. With the architectures I feature, some are very specific, and some are more ambiguous.

I think ultimately that they are visual maps to have viewers engage in conversation with one another about whatever connections they may make, or non-connections they may make, or nonsense they see out of it, or actual, you know, linearity that they see out of it, and anything that they might think about. And tension and disagreement between viewers is very important for me, as are the things that viewers see in common. But I think rather than me having a common thesis, like “Purdue pharmaceuticals was an asset of the CIA,” or something, I'm a lot more interested in ambiguity and nonsense, in terms of paralleling the way that information is absorbed and processed. And also as a way to kind of visualize and talk about the decentralization of power and how power structures work at the current stage of the State that we are at.

BL: When did you become interested in diagrams? When I first saw Edifice, I was thinking about similarities to the work of someone like Mark Lombardi, but his diagrams are more informational. They’re not about working with images.

NA: Lombardi was actually the first artist that my mentor at CalArts turned me on to when I started graduate school, and he's been extremely influential to my practice. Especially the way that diagrams are a visual language. Seeing his work also enabled me to treat a diagram as a work of art, rather than as an infographic or something like a teaching aid. I do kind of think about these diagrams as pedagogical tools, but at the same time, they're absolutely not meant to teach. And I don't think Lombardi intended to teach either. He was definitely more investigative than I am at this point. He set a lot of the framework for my interest in using these types of aesthetics, but I think Lombardi was trying to make sense of his material. I don’t try to make sense of things even though I began the work for my recent show, Edifice, with a thesis about raving and how what began as a countercultural gesture in post-industrial areas became institutionalized and commodified over time. I think that thesis was really important for me, just understanding the momentum of early raving in Britain, Detroit, and Chicago. And then seeing, you know, seeing what Coachella is today.

BL: Do you have any personal investments or connections to dance culture?

NA: No. A lot of people have asked me that. And I mean, I think, to be completely honest, the intention of this exhibition, when I was initially figuring out what I was going to do, I had just left my job at a needle exchange, and I had really seen harm reduction, the radicality of harm reduction become totally bastardized. And, at least where I was working, I watched it go from being a space that was essentially created for people that use drugs to build relationships with service providers, and therefore create power amongst drug users, to a service provider that was bound by grant stipulations and deliverables and making quotas; the former obviously being the scariest thing for the State in the history of radical politics. The needle exchange just became an entity, rather than a space to build power amongst essentially the poor, people who use drugs, and people who live on the streets.

It was really around 2022 when that became very evident—Biden literally mentioned harm reduction in one of his State of the Union addresses. It was like the administration just tapped the harm reduction sector to essentially manage the opioid epidemic. Just watching what was essentially the commodification and bastardization of harm reduction really happening in front of my eyes, and being so affected by it as someone who is a former heroin addict, I thought that what’s going on here is so powerful as like a skeleton and like a concept, but I’m not ready to make work about harm reduction and drug users, it’s just too much right now, emotionally.

And I guess my only connection to dance culture and rave culture would be through harm reduction. Like, there are some serious parallels just because they're both drug-using spaces. And there was such a clear line and wealth of scholarship around the institutional transformation of rave culture. So, it was kind of just an easy transition. I wanted to use these ideas somehow, but I wasn't quite ready to do it with the personal experience I was having.

BL: I’m curious to hear more about how you approached sourcing and structuring images, making reference to these cultural forms shifting across time.

NA: There are two parts to my approach. Number one was, I would pick a subject and surf the hell out of the internet pretty rapidly. And then if I found an image that I found compelling, and fit within the structure, or the specific research that I was thinking about for that moment inside each diagram, I would choose to use it.

Number two would be that I studied with the artist Charles Gaines, and he really taught us that the thing that makes an artwork important is the Kantian definition of the sublime. A work could be pleasurable or displeasurable, but it has to move somebody. It was really important to me that the images were conceptually, historically, and narratively fitting, that they were performing as significant pieces of the “story” I wanted to tell here, but that they were also visually striking or relatable.

There was an image of the Phish girl with the dreadlocks, and people kept sending me messages of that specific image. And that kind of image works as an entry point to think deeper about the work and certain moments within it. From what I understood, that is an image that people recognized, especially people of my generation, who grew up on MTV, and grew up on YouTube, and grew up on memes, and grew up on these images we’ve seen over and over and over again. I think it successfully worked as an image where people could become curious as to why it was in one of these works at all.

In so many ways, my practice is research-based. But having these works as just pieces of research would be a disservice to the aesthetic of the work. There's something that I want to explore around all of this that’s a lot more libidinal than I think research can do justice to. Research is a really good starting point. But I'm not interested in having a specific image always fit into my intention with research in the beginning, if that makes sense. Some of the images do, but I'm more concerned with the quality of the image, or how it makes people feel, than any sort of actual thesis.

BL: I want to know about this show, how it emerges out of other things you were doing, and if making it made you want to deviate or elaborate on this style of work?

NA: I definitely want to do something like this again. I’m not sure what kind of iteration I want to do; I think for this project, the subject matter was kind of specific enough that it allowed me to form the aesthetic in a particular way, using very simple and cheap material and pretty rudimentary forms like Photoshop. But I think what I am interested in is zooming out a little bit further and getting less specific as to what these diagrams are about.

The next project that I’m thinking about in terms of diagramming concerns the evolution of major Western architectural movements, specifically modernism to post-modernism to parametricism to Fascist architecture, and moving outwards to different cultural connections and implications these structures have. I’m still kind of in the planning phase for that. I mean, it sounds corny, but where does it come from? I’ve always been really interested in diagramming. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s just something the universe gave me, but I’ve always just thought about things in terms of connections and associations, and I don’t really know why. I was an Urban Studies major in college, so getting into my studies at the New School, if I thought about the urban landscape, I would really think about it as a diagram, and think about connections, and I think that’s where the architectural aspect comes in. Like thinking about certain types of architecture I’d see around the city, or certain parks, or how certain boulevards and freeways were these borders for different gangs in different neighborhoods. It's just how I thought about the city.

I think where the idea came from for this specific show, I was just really intrigued by the definition of the word “edifice,” which is essentially the skeleton of a piece of architecture or a complex body or complex system. I was reading a lot of post-architectural and architectural theory from writers like Mark Wiggley and Felicity Scott, and thinking about the way that they would talk about contemporary culture by way of architecture, and it just kind of made sense to me, so I went there. I guess this is probably important to say, one of the buildings, the edifices, that takes place across a lot of the diagrams is the skeleton of the United Nations building.

I’ve been very intrigued by the UN ever since I read Felicity Scott’s Architecture or Techno-Utopia. She talks about the UN and the architecture of it as this modernist trope that was revolutionary in the time of the late 1950s, 1960s, and then kind of became a symbol of corporate architecture over time, while still housing the UN, which was thought about as like this radical international body that would solve social issues. Humanitarianism was not a revolutionary idea, per se, but it was a significant idea for the counterculture of the time. In watching humanitarianism become commodified over time, there was this parallel corporatization of physical space, where you can really consider the architecture and what was happening inside the architecture simultaneously.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.