Robin F. Williams on Sustainability and Calling People In

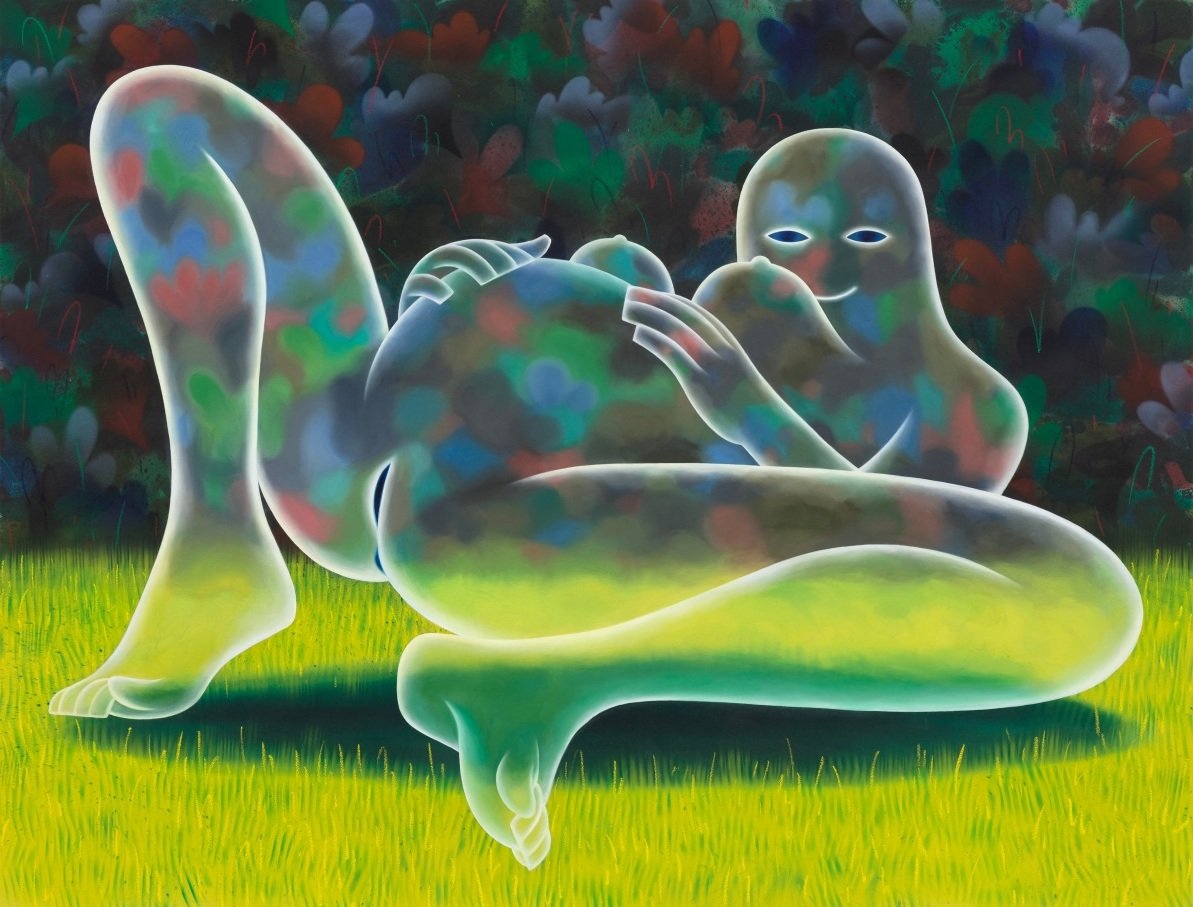

“If an artist is working with a gallery, the gallery has an incentive to listen. If multiple artists at a gallery feel the same way, they can form a coalition,” says Robin F. Williams, a Brooklyn-based painter known for her luminous figurative work, about the power of collective organizing in raising awareness around sustainability discourses. In a conversation with Xuezhu Jenny Wang, Williams discusses her involvement with Artists Commit and the challenges of balancing sustainability with artistic production. She also reflects on how themes of hierarchy, reciprocity, and human relations manifest in her work, offering insight into the intersections between art, commerce, and environmental ethics.

Xuezhu Jenny Wang: How did you get involved with Artists Commit?

Robin F. Williams: In 2020, I released a limited edition print with Pace Prints for the Environmental Defense Fund. Then, when the pandemic hit and everything went virtual, I started thinking more about the environmental impact of the art world. I also started looking at my interactions with galleries, institutions, and art fairs, wondering how to integrate activism into those spaces. That’s when I first got involved with Galleries Commit, which was formed before Artists Commit. It started with gallery workers signing an open letter, committing to more climate-conscious practices in their sector. Many artists signed on as well, and eventually, the artist side of the group began organizing separately. Many of the founding members of Galleries Commit are also on the leadership team of Artists Commit, so it all evolved together.

XJW: Since getting involved in climate action as an artist, how has your practice changed in pursuit of the cause?

RFW: One of the biggest shifts has been working on the Climate Impact Report initiative. It’s an audit you can conduct on your exhibition—either from start to finish or retroactively—to assess its environmental impact. That process has been eye-opening. We’re working to make it more accessible at all levels of the art world.

On a personal level, this work has made me prioritize sustainability when considering collaborations with galleries and institutions. Having experience with the Climate Impact Report and years of activism makes it easier for me to say upfront, Hey, this is part of my practice and values. If we work together, we need to discuss sustainable shipping and exhibition practices. It also helps me set boundaries, like deciding I won’t fly somewhere just for an installation—I’ll only travel for the exhibition itself.

Being part of a collective effort gives my decisions more weight and context. It removes the feeling of going up against the system alone and provides a sense of integrity and community support.

We’re not just trying to mitigate the climate crisis; we’re also building resilience and support networks. As the world becomes more uncertain, having connections with like-minded artists has been invaluable. For example, when the fires happened in LA, we had members actively organizing relief efforts. Because we were already in touch, we could immediately collaborate and offer support.

XJW: Have your sustainability-related work ever limited opportunities when it comes to working with institutions or art fairs?

RFW: It’s hard to say for sure, but I suspect it has—at least once. Without getting into details, it involved an art fair, and a proposal was rejected. It’s impossible to know if my environmental stance played a role, but it’s something I’ve thought about.

That experience was a learning moment for me. I approached the situation in a way that was maybe too independent—I tried to push for change without fully leveraging the strength of our coalition. That was a mistake. I’ve realized that this kind of activism is much more effective when done collectively. The whole point of organizing is building power and creating a unified front.

That’s also why our approach isn’t about calling people out—it’s about calling them in. We want to work with institutions, art fairs, and galleries to encourage accountability at every level of the art world. Our goal isn’t to shame or cancel anyone but to highlight that sustainability is a shared responsibility.

XJW: Many have noted the difference between the art world and the art market, the latter stipulating the overproduction of objects. As a commercially successful artist, do you feel pressure to produce and contribute to this cycle constantly?

RFW: That’s an existential question for any object-maker. I’m not going to pretend the art market doesn’t influence my practice somehow. But we’ve also been careful not to impose a rigid ideology that excludes certain types of artmaking.

All humans take up space, participate in capitalism to some extent, and produce some level of carbon. The question is, how can we make more intentional choices? Sustainability doesn’t mean erasing one’s practice—it means considering its impact more deeply.

For example, I stopped using masking tape in my work because I realized how wasteful it was. It’s a small shift, but it made me think differently about my materials. Similarly, we help artists assess their environmental footprint through the Climate Impact Reports. The biggest impacts in the art world generally come from travel, shipping, packaging, and energy use in studios and exhibition spaces—not necessarily from an artist making physical objects. That said, the more stuff we create, the more it needs to be stored, transported, and circulated.

Ultimately, the goal is to shift the conversation so that sustainability becomes a shared value and influences culture at a grassroots level. It’s about striking a balance.

XJW: When you approach institutions and galleries, what’s the strategy? Why should they prioritize this? What’s the language you use to get institutions on board with sustainability?

RFW: We’ve had some success going straight to certain fairs and asking them to do a Climate Impact Report. Instead of starting with, “You need to change everything—you’re being wasteful and horrible,” it’s more like, “Hey, we’ve developed a method of taking inventory and accountability of our practices. It can scale to an art fair level. Would you be willing to take a look at your climate impact and be transparent about it?”

If an artist is working with a gallery, the gallery has an incentive to listen. If multiple artists at a gallery feel the same way, they can form a coalition. A single artist might not have enough influence, but collectively, they have leverage. The art world runs on the labor of artists. It’s about artists and workers recognizing their power and reclaiming some of their influence.

XJW: Much of your work deals with the representation of women. Are you interested in addressing themes of sustainability directly in the thematics of your work?

RFW: I actually do think about these issues in my work. It might not be the first line of a press release, but I approach the topic from different angles—sometimes more explicit, other times metaphorical or implied. Climate change intersects with every other form of oppression and exploitation. I’m always thinking about power dynamics and systems of hierarchy vs. systems of reciprocity. We treat ecosystems, as well as people, as free, expendable resources. The way we treat the planet—as an endless resource to be pillaged—is a mindset that repeats across every system of oppression.

My work is mostly figurative, and I feel that people respond more to personification. One reason we struggle to relate to the environment is that we think of it as inanimate, abstract, or non-entity. With my paintings, I try to blur the boundaries between bodies and the environment to challenge individualism and hierarchy. But it’s an ongoing question. I just made a huge landscape drawing for the first time and thought, “What does this mean? Is this a new direction?” Maybe I won’t always paint figures, or maybe I will—I don’t know.

But also, I think it’s important to say that you don’t have to make work about climate change to engage with these issues. It’s not a requirement. Sometimes, once artists start thinking about sustainability, they realize their work is already about it in ways they hadn’t considered. This shouldn’t be a disqualifying factor—it’s about making sure everyone feels welcome in the conversation.

XJW: The point about systems of hierarchy vs. reciprocity is fascinating. Could you share more about how this shows up in your work?

RFW: I paint a lot about AI, particularly Siri. We’ve collectively decided Siri is a woman, but she has no body. She exists in this abstract virtual space that we also treat as an endless resource. It’s like, “Oh, to avoid exploiting real women, we’ll create a virtual woman and exploit her instead.”

That also ties into trans rights and conversations about the body. Siri has a voice, a gender, but no physical form. You can change Siri’s voice settings, but most people just assume she’s a woman. We’ll unquestioningly accept that an AI is female, but we won’t let a real person define their own gender. That cognitive dissonance fascinates me.

And Siri, for me, is a way to connect all of this—AI consciousness, the body, the environment, sustainable energy. Power structures keep rolling forward by exploiting different groups at different times, maintaining this illusion of plausible deniability about what’s ethical and what’s not. It’s all interconnected.

XJW: How are you feeling right now? And how do we, as a society, move forward?

RFW: Honestly, it’s terrifying. I’m really grieving the outcome of this election. But even if it had gone the other way, there would still be a tremendous amount of grief. The reality of climate change is deeply sad and scary, and no one politician or person is going to fix it for us. That being said, I wish it had gone the other way for so many reasons.

What keeps me from feeling completely hopeless is the fact that we’ve built something as a group. We know we’re not going to solve the climate crisis single-handedly, but we’ve created a network of care, reciprocity, and shared values. The more we build these networks and practice being there for each other—using our creative energy to sustain ourselves in a way that’s joyful and meaningful—the easier it will be to navigate everything. It helps to focus on my own sphere of influence. We’re all scared by these big problems we can’t control, and we desperately want solutions. But I feel most grounded in a real, concrete, grounded community.

Organizing is hard. It’s a lot of Zoom calls, disagreement, working through conflict, impatience, and impulsiveness. But it’s worthwhile because it makes us safer and more resilient.

XJW: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

RFW: You can always visit our website, artistscommit.com. There are a lot of great resources, like examples of climate impact reports and a form that artists, galleries, or institutions can use. There’s also a database of other resources—climate calculators, handbooks on best practices for materials, and more.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.