Information in the Windshield

The sound within KAJE comes from multiple sources: electromagnetic field microphones connected to a mounted hard drive and a fenced-in AC unit tucked by the entrance, previously programmed loops of fan outputs spitting out sonic exhaust, and the live-generation program synchronized to processing stages of Cache Machine’s central image diffusion model. These sounds move through white noise, dramatic crescendos, processing whirs, and crashing disintegrations. Often, a particular refrain will emerge against a constant, low hum.

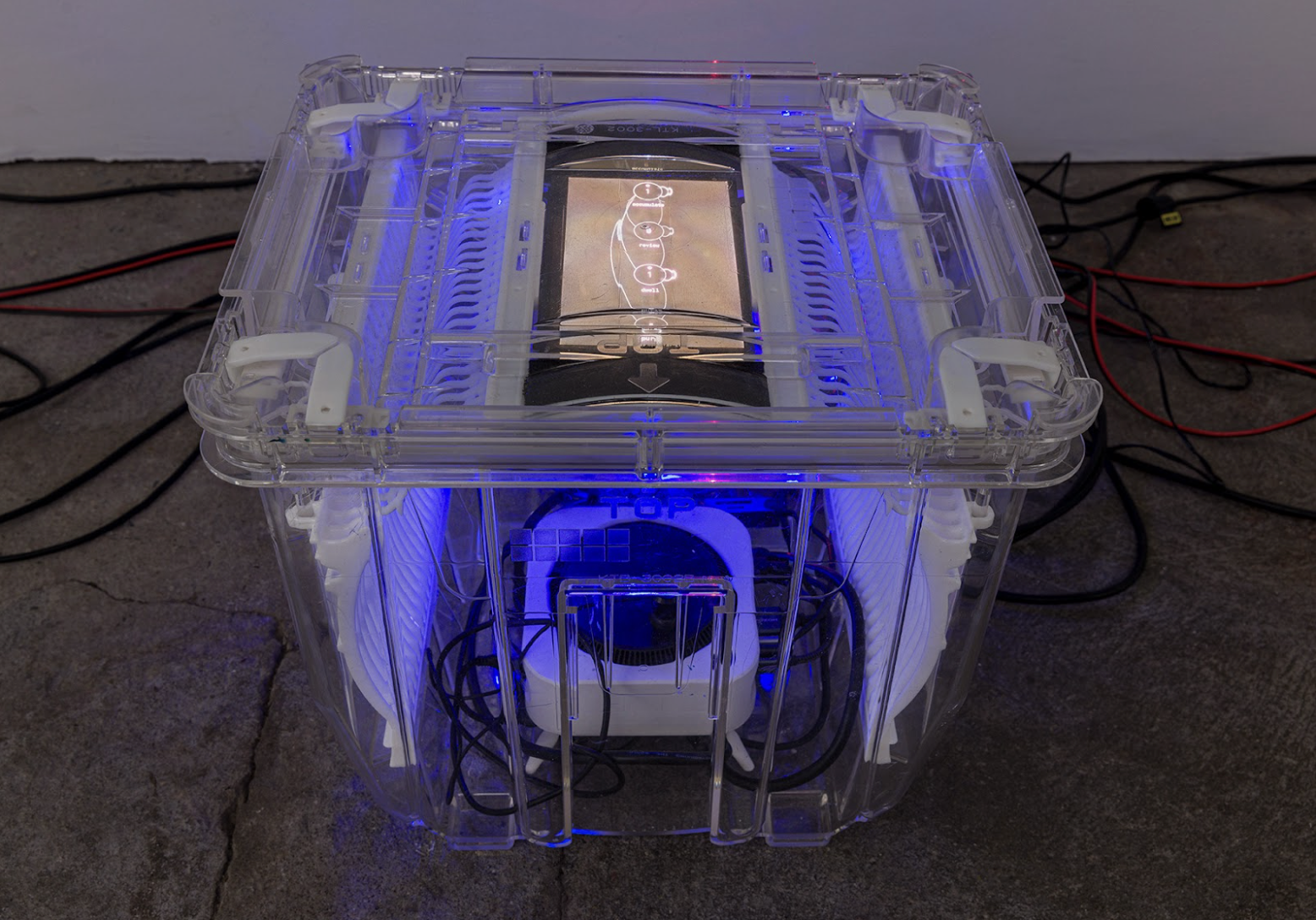

The exhibition, produced by the record label collective 29 Speedway and founder Ben Shirken, aims to make the otherwise sequestered soundscape of data centers—decibels heard only by technicians and surrounding residents—available to listeners in the concentrated space of the cube. Two salvaged Ford Escape hatches hang adjacent to each other at the exhibition’s center, where a series of AI-generated images flicker upon the rear windshields (rendered as a nod to Klee’s Angelus Novus [1920]). The images are generated by a program designed to move through stages of generation and deletion: “accumulate,” “review,” “dwell,” and “purge,” a stochastic and unpredictable cycle of successive images, then erased from the program. Viewers can watch the progression on a screen set in a translucent front-opening unified pod, a container manufactured to hold silicon wafers throughout shipping and production. The images are generated by prompts on broken computers, surveillance imagery, and technological detritus—often the partially-denoised figurations resemble abandoned wiring and infrastructure, a low-res reconnaissance photograph, or a night-vision survey. Each time an image is generated, the windshield wipers are set into motion, ticking to the temporal cues of new compositions to scan; an accompanying sound, a brief tinny crescendo, signals the image’s generation as well.

Colliding with the soundscape are tail light spasms and dissonant lighting patterns which alternate between blackouts, strobes, and ominous blue and red washes. On the gallery’s floor are a series of coin cell batteries, 3-D printed in various states of compression and expansion. The canister-like figures, glowing in purple hues, are a nod to the supply chain of materials that make information possible, though here they are inert—echoes of their operational function. Across from the hard drive is a small screen showing dashcam footage, algorithmically distorted into lightly surreal forms traveling rapidly through highways and side roads. The accelerationist visuality serves as an alternative to the rearview form of the cars’ hatches: the future toward which technology moves and the intimation of what it might leave behind. Actual detritus is somewhat absent from the exhibition, however, and the exhibit works best when thinking about sound and image as the visual output of in-visual processes, the trace of something not usually seen or heard.

Hung from the ceiling is a multi-channel speaker that directs a programmed sound of humming fans around the cavernous room, inviting viewers to move around the space in accordance with the sound’s dispersed location. On January 16th, the audio artist C. Lavender performed with recordings of a Serge modular synthesizer, utilizing the alternately erratic and droning environment for a composition that oscillated between high, whining tones and repetitive mechanical whirs. With this addition of a directed, even narrative, soundscape to the space, the images on the cars’ hatches read as a navigational route through operational images rather than a mere accumulation of effects—a searching, first-person shooter sort of view ingrained within the aesthetic of automated scanning that can otherwise be anonymized and overwhelmed by the sonic component of Cache Machine. As the performance shifted to a harsher, emergency-state sequence of blaring staccato, the task of making figure out of noise—native to both electronic composition and image generation—was injected with more urgency.

Reminiscent of the spatialized sound installations by 20th-century artists like Edgard Varèse, Francois Bayle, and Karlheinz Stockhausen, a scattered sound localization is here transposed onto an address of data’s infrastructural opacity and obfuscation. Rather than focusing on the strictly aesthetic parameters of listening and presence, though, diffusion becomes a question of how the noise emitted by processes of image generation and data cooling might be rendered as a physical space in which the components of data infrastructure illuminate the materiality of sound.

For what it’s worth, Varèse and Stockhausen had the advantage of massive World’s Fair spaces throughout which to direct their immersive compositions, foregrounding the scale at which sound installation might communicate its aesthetic ideal. Cache Machine, on the other hand, makes its reverberations dense, cramming together disparate parts of a system in an uneasy marriage of auditory overload and the presentation of an ad-hoc supply chain. That the room is segmented into instances of manufacturing debris—a car, a battery, a cooling system, a hard drive—points to an attempt to connect contemporary data culture to a longer history of manufacturing, as well as to represent sites that might serve to visualize a production process often hidden from public view. But its tour of material parts, which constitute an immaterial system, can render the sanctioned physical pieces of the exhibition at odds with the immersion and totality which spatialized sound typically asks of its form.

Bringing viewers into the “world” of information is here a matter of showing them the coincident steps that are involved in image generation and data cooling rather than visualizing the porousness of a system. It’s an approach that often struggles to reconcile the discrete nature of nodes, to construct an aggregate form of their connectedness. The largely incidental images contained within the windshields—meant a nod to a kind of rearview-facing nature of image generation, which performs operations performed on past data and leaves waste in its wake—can feel secluded from the computational processes which really are making them appear; then again, as a nod to the diffuseness of networks which resist any kind of visual totality, perhaps it works best as an experiment frustrated by limits imposed from without.

Cache Machine was on view at KAJE from January 10 through 25, 2026.