Gorgeous & Guilty: In Conversation with Suzie Maez

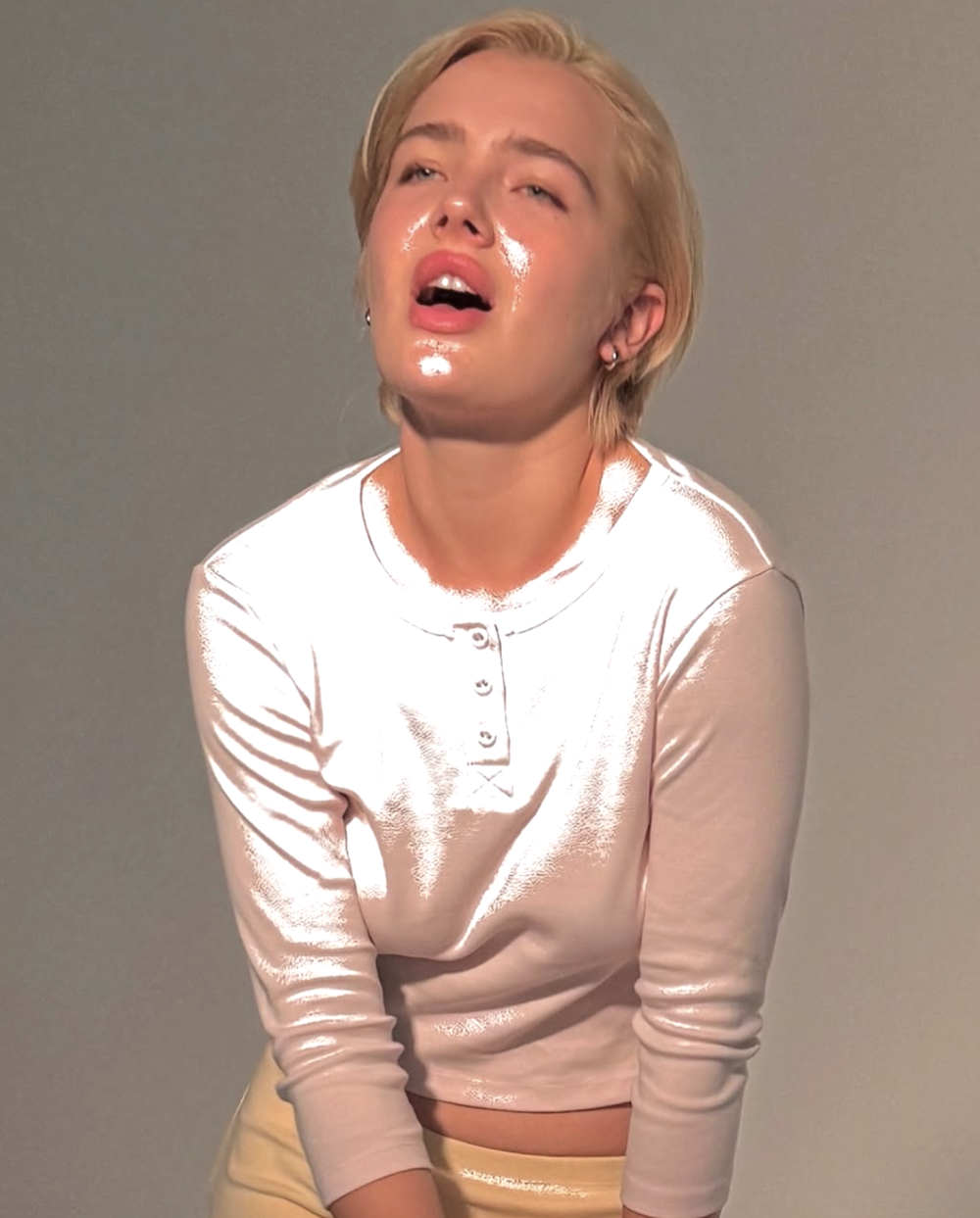

Suzie Maez believes that people don’t always notice the image they are standing inside. An iPhone photographer and filmmaker, Maez seeks to democratize street photography entirely by capturing the overlooked, the imperfect, the tender, the absurd, and the discarded. She finds beauty and symmetry in groceries swinging from plastic bags, in the light reflecting off a stranger’s glasses, in lingerie left on the street, and in the absolutely ordinary. For her debut photobook, Gorgeous & Guilty, published by Pomegranate Press, Maez shuffled through her vast archive until surprising patterns and pairings emerged. In the wake of her first published project, this conversation explores the everyday ethics of looking and her commitment to capturing imperfection.

Audrey Weisburd: Your work feels diaristic and spontaneous. How consciously do you compose an image versus surrendering to whatever arrives?

Suzie Maez: 90% of my work is impulsive. I surrender to the moment. When I’m running late or when my map takes me the wrong way, that’s when I get my best photos. I get to walk around and catch something I never would have if I’d made that bus or flight on time.

There’s nothing wrong with planning a photo, but in my work, it means much more to be honest about exactly what’s happening. If there’s a finger in front of the camera or someone walks by while I’m taking a photo, that becomes part of the scene. That’s what makes the image special—its rawness.

AW: From discarded rubber gloves holding hands in a sewage grate to groceries swinging in a bag, your work makes the familiar strange and the strange familiar. Have you always seen the world this way?

SM: Growing up, I loved two things: film and music. Better yet, the way that music complements film. The more I watched, the more I wanted to make a film of my own. Later, one of my graphic design classes asked us to bring in our portfolio, plus something unrelated. I brought in photos I had taken for fun. Every professor told me the same thing: the design was fine, but I should really pursue photography.

After that, I started going out of my way to shoot. Taking trips to New York, I started noticing these special characters emerge. I thought of them as people I’d cast in a film because of their distinctive look or style. Why not make your life a movie? You get to cast the people you find captivating.

AW: What draws you toward strangers and the mundane theatre of daily life?

SM: Confidence in imperfection. I don’t go out into the world searching for these characters. When the subject is a person, I’ll look up, see them, and just know. They’re not thinking about anyone around them—they’re in their own world. They’re dressed the way they want, smoking their favorite cigarettes, maybe their arms are crossed a certain way. Or they might have none of those things, and it’s simply an aura that draws me in immediately.

I’m also drawn to objects. Spills, things on the ground, things that look ugly. If you can almost smell an image, that’s interesting to me. When I see something disgusting, I’m drawn to it.

I want my photography to feel relatable. If you take something liminal or ugly and highlight it, it can be celebrated more often, humorously so. That’s why I like to focus on very ordinary, even dull moments. By paying attention to them, they become worth noticing.

AW: How do you navigate the ethics of looking at people without them knowing?

SM: It comes down to knowing your why and your intention. When you understand why you’re taking a photo and who you’re taking it of, freedom can be found. Empathy is essential. You have to ask yourself whether this looks like someone who would want their photo taken.

There’s a certain confidence required in trusting your judgment and being empathetic toward your subject. You don’t always get the chance to ask; position and context matter. Many photographers don’t want to lose the moment, because once you ask, it changes and becomes posed. The beauty is in the moment before someone sees you.

AW: What about the iPhone specifically informs your art?

SM: I have a very obsessive habit of documenting, and because of that, I want to use the thing that’s with me 24/7. My phone feels like an extension of myself.

I don’t want to take photos of things that feel redundant on social media. There are already so many images of the same subjects. I assist Hannah La Folette Ryan in the iPhone Street Photography course at ICP, where she talks about this book called The Social Photo, which talks about how, as a society, it becomes cool to photograph something iconic, like a famous bagel shop, and suddenly there are thousands of photos of the exact same bagel. That level of abundance can be scary. I’m trying to take photos that aren’t that.

AW: You subvert what the iPhone camera is typically used for. It reminds me of being in a museum where everyone crowds to photograph Starry Night or the Mona Lisa. Instead of photographing the painting, you would be more drawn to photographing the people fighting to take the photo. The overlapping hands and screens become the image. Do you feel as if you are taking the photo under the photo?

SM: Exactly. People don’t always understand the image they’re standing in. I have this video from the International Balloon Fiesta in New Mexico during the Special Shapes Rodeo. One balloon was shaped like a face and was being inflated. I was filming it normally, and this man stepped directly into the frame, right next to the balloon, making the exact same face. I remember thinking, he has no idea what image he’s standing inside.

AW: What is the story behind your photo of the ballerinas, and how do you capture movement?

SM: Every time I go to the ballet, I take photos of the ballerinas using long exposure. It makes everything look feathered and turns into this beautiful, painting-like image. On the other end of that, I also post videos with almost no movement. I call these “breathing photos.” My work actually started with those stills. People would comment, “I didn’t even know this was a video until the bird flew by.” Those pieces are meant to make people slow down and be patient.

Many people think the iPhone is limiting, but you can do so much with it. I have videos from 2022 where I took the same kinds of clips I usually do, but reversed them—people walking down the street backwards, for instance.

AW: How do you see the future of art in the digital age, and the iPhone as a creative tool?

SM: Since I started really pursuing iPhone photography and film in 2020, I’ve already seen a large increase in people working this way. I would say at least triple the number of people are taking iPhone street photography seriously compared to when I began. Many people may have always had the eye but not the funds to afford a nice camera. The doors have opened. Someone like Sam Youkilis, for example, has opened up many possibilities. He’s also an iPhone photographer, but he’s more focused on travel, food, and fashion.

AW: How does New York illuminate your work? How would your work change if you were based in a different city?

SM: New York is incredibly inspiring. I love its grit and its chaos. But every place has its own theme. I’m inspired by what might seem like the most desolate, least desirable locations—places where people might feel stuck, like if your flight gets delayed and you suddenly find yourself in the middle of nowhere. I lean into that. It becomes a game. I ask myself, what’s the weirdest place I can find?

I could shoot from anywhere. Someone could put me in a box, and I’d find a way to photograph it, because I’d be thinking: this is strange, no one’s ever been in this box before!

AW: Your work feels like the younger, more playful cousin to the documentarian John Wilson’s work. Is this a fair comparison?

SM: For the past few years, people have commented on my TikTok saying they’re convinced I’m John Wilson’s burner account. I always take it as a compliment. Our ways of seeing feel deeply aligned.

In 2021, a friend told me my work reminded him of How To with John Wilson, which I hadn’t seen yet. When I watched it, I was completely in awe. For the first time, I saw someone doing something very similar to what I was trying to do, but on the fullest possible scale. He built an entire universe out of observation. I’ll stop to photograph something on the street, and people will look at it and clearly think, why is she taking a photo of that piece of trash? Seeing someone like John Wilson doing that kind of work on HBO was incredibly inspiring.

AW: Tell me about your debut photobook, Gorgeous & Guilty.

SM: The title comes from a Henry Mancini song. It reflects the idea that imperfection doesn’t negate beauty but instead carries its own story and radiance. In the book, I wanted to include both the more traditionally beautiful images I’ve taken over the years and the riskier photographs that feel especially textured.

Some spreads function as visual parallels, while others tell a story. Sometimes you’ll see two very similar images paired together. Other times, you’ll see two different locations or subjects that feel like they belong in the same scene.

AW: What is your dream project?

SM: My long-term goal is to continue archiving my work. On social media, images can feel fleeting. People swipe past them and forget. I want to focus on preserving my work in a way that keeps it meaningful, both to me and to other people.

Separately, a project I hope to share soon involves my audiovisual work. People often tell me they wish my videos could live in a coffee-table book. My dream is to find a way to present that work so it can be easily experienced and enjoyed. Ideally, that would take the form of a solo show featuring sound and visuals. Right now, that body of work is difficult to share in large spaces, but I feel like that’s changing.

AW: What are you currently working on?

SM: I’ve been working on a framed piece rooted in nostalgia and family. Growing up, my family had one of those collage frames with different shapes that we’d had since the eighties. When my parents were moving out of my childhood home this summer, I brought it back to New York and realized I didn’t have any framed photos of my friends or family in my apartment. The space felt cold.

I wanted to recreate that frame in aluminum. I asked four people to send me photos from their family archives, placed them into the frame, and then photographed the piece itself. The project is about nostalgia and the family unit. It feels human and tender, and that will always be what matters most to me.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.