Theaster Gates’s Harvest Season in Chicago

Theaster Gates—the aesthetician who effortlessly leverages form and content through his unforgettable installations; the musician who leads the gospel-rooted experimental music ensemble The Black Monks that unites free jazz, blues, and electronica into a kind of spiritual, chanting poetry; the steward of collections that span from UChicago’s art history department’s glass lantern slides, Frankie Knuckles’s vinyls, Johnson Publishing’s Ebony and Jet magazines, and Ken Mehta’s True Value hardware stores; the “real-estate artist” who developed his public art “empire” at the Great Grand Crossing neighborhood through a series of urban revitalization projects—is first and foremost a potter.

Born and raised in East Garfield Park on the West Side of Chicago, Gates attended school for urban planning, ceramics, and religious studies, and spent a formative year in Tokoname, Japan, studying pottery. The religious connotation of clay, as well as a process of making ceramics that is performative and transformative in nature, threads through Gates’s work. In one of his early performances in the late 1990s, he sang while wheel throwing. A Clay Sermon, his seminal solo exhibition in 2021 at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, highlighted not only the spiritual legacy of clay but also its material history punctuated by slavery, colonialism, and global trade. At his current exhibition at Gray Warehouse, OH, YOU’VE GOT TO COME BACK TO THE CITY, new stoneware vessels sit atop assorted stone or concrete blocks that have been arranged into a five-by-eight grid, evoking a graveyard solemnity. Gates’s continued endeavor of merging African American and Japanese traditions is evident here with pieces such as the mustard yellow Summer Chawan (2025) and the rich umber Tokoname Vessel #12 (2025). On the opposite side of the grid, sitting atop a thin, long side table supported by sleeper wood, a lone, sage-glazed stoneware Small Mountain Formation is not unlike an abstract interpretation of a bonsai on rock.

However, “As soon as [he] stopped using clay, the contemporary art world became interested in [his] work,” the artist recounts in his art21 portrait. Gates’s other early work includes assemblages of found or recycled materials that allude to urban decay. His Cosmology of Yard at the 2010 Whitney Biennial, for example, was a temporary communal sanctuary constructed from wood salvaged from a closed gum factory. Gates traces these impulses behind his work back to his upbringing: “My neighborhood is being torn down systematically, and I felt that there was nothing I could do about it,” he says in the video. And to reuse, to rebuild, is for him “to imagine [that] the world was not a series of abandoned buildings but a world waiting to be restored.”

It’s perplexing how Gates rose quickly to superstardom in the international art world before being recognized by his home base in the form of an institutional solo, if this is still the way we measure an artist’s success in their career. He’s packed the Whitney Biennial, Documenta, Venice Architecture Biennial under his belt and shown widely across the U. and in Europe, but he has never had a full institutional solo in Chicago, until now. The fall of 2025 is the harvest season for Gates, but mostly for the city. Soon after the ribbon cutting of the Rebuild Foundation’s newest project, The Land School, opens the artist’s well-overdue first museum solo at the Smart Museum of Art, on the University of Chicago campus, Unto Thee.

His concurrent gallery solo is at the Gray Warehouse, a former machine shop of 5,000 square feet located in Chicago’s West Town industrial corridor. This is Gates’ fourth solo exhibition at Gray, and third at Gray Warehouse. Every time, he takes over the Warehouse’s main room with a monumental installation; be it the sleek black platform with a neon sign in 2019 (Every Square Needs a Circle) or the stacked wire container containing assorted hardware stuff in 2021 (How To Sell Hardware), there’s always some extra strings of kinship that pull the work firmly to the space it inhabits, like a specter from Chicago’s rusty past that then becomes a glow of history.

OH, YOU’VE GOT TO COME BACK TO THE CITY unveils Gates’s new screen-printed paintings that feature a key industrial medium, bitumen. A black goo distilled from petroleum that’s used for road surfacing or roofing, similar to tar, Gates is known to deploy this water-resistant binding material in his work. In interviews, Gates, the son of a roofer, often quotes his father’s profession as a starting point and continued influence for his artmaking. Quite tongue-in-cheek, Advertisement (2025) features a phone number, “1-800-ROOFING,” drawn on top of patches of rectangular rubber pieces of various sizes that are coated with acrylic colors. Advertisement looks like a smoky version of a Mondrian color grid, unleashing unbridled energy—a deconstructed modernist attempt soaked in nostalgia. On the other side of the town in Hyde Park, Gates’s other exhibition at the Smart Museum also features a new monumental sculpture, Slate Roof (2025), which takes up almost half the museum’s width. Old slate, originally from the sloped roof of the university’s Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, has been tiled into one single giant roof plane supported by a custom-made steel structure, acting as a devouring backdrop in shades of blackness.

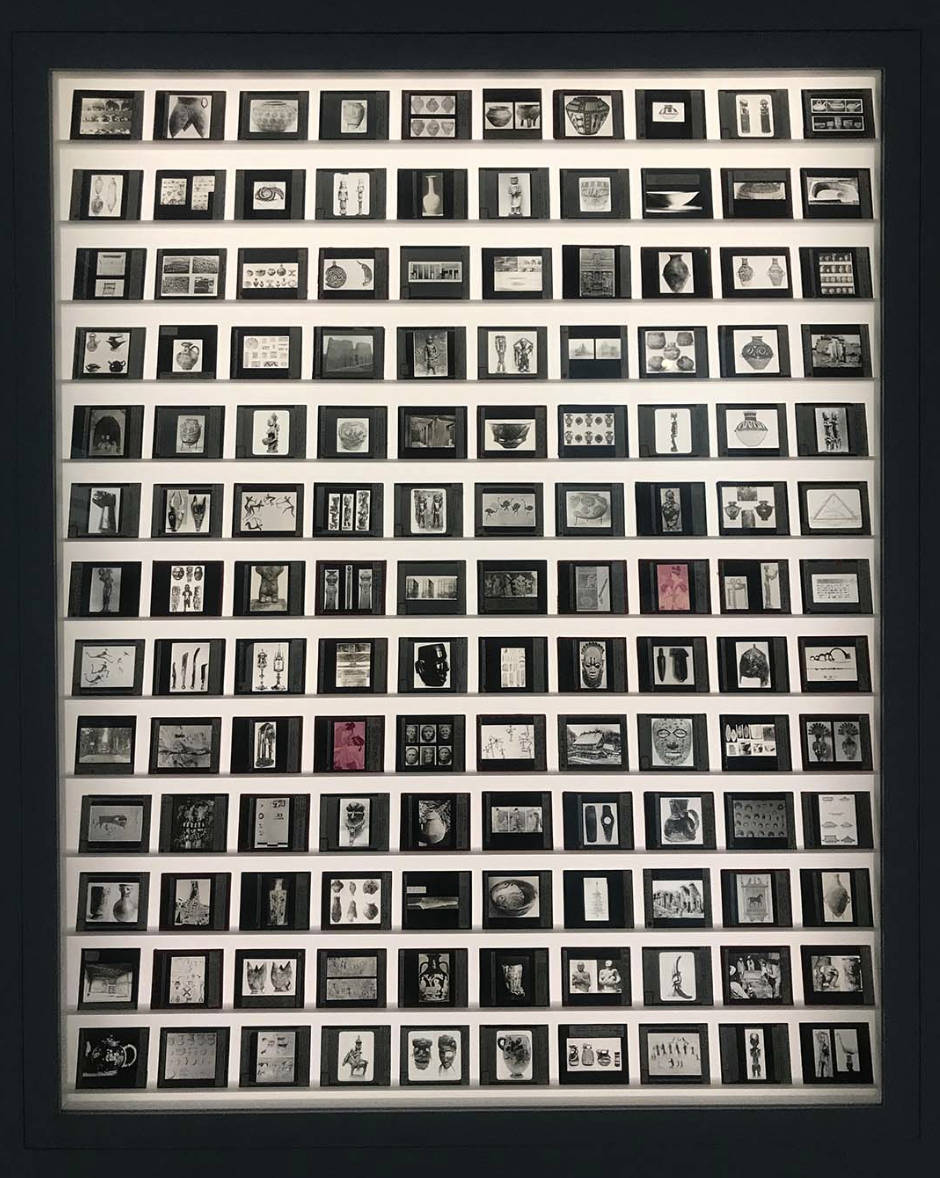

Gates is a self-perscribed “keeper of objects.” His effort to collect found objects and turn collections into environmental installations chimes with the conceptual sort championed by Marcel Broodthaers, Gabriel Orozco, and Mark Dion. A gesture fitting for the context of a collecting university art museum, Unto Thee highlights Gates’s numerous collections-turned-art-installations, such as the Muguette and Lucien Guenneguez Collection of African objects; the music collection of the late Chicago-based DJ Dinh Nguyen; and the Glass Lantern Slide Archive, comprising 72,000 slides assembled by the university’s art history department. The monumental displays of these collections are engulfing. But for the sake of a museum show, they are not readily tactilely accessible to the visitor. The installations thus overwhelm by operating purely on aesthetic and conceptual terms: Their massive presence conveys a sense of history without disclosing what those histories entail. This is not to say, though, that audience members are completely shut off from the content. Gates creates curated, albeit limited, pathways to accessing the materials, such as his film Art Histories: A Reprise (2025), made from the digitized glass lantern slides and the series of programming at A Listening Space earlier this year that activated Dinh Nguyen’s vinyl collection.

COME BACK TO THE CITY, on the other hand, features Gates’s reuse of found objects. The rows and rows of nameless plinths, some chipped, some having writings on the side, some pedestaling his ceramic vessels, are from his stone repository, a selection of granite, marble, scholars’ rocks, and concrete blocks that he sourced from demolished buildings in Wisconsin. Instead of bringing in preconceived meanings—the aura of history, if you will—that are derived from exceptional provenances, these stones weigh in their physicality that is a testament to urban decay and the prices we pay for what is whitewashed as “progress.”

Transformation is in Gates’s approach to almost everything he does. He elevates the status of discarded materials, rearranges archives, and puts abandoned buildings to use in good faith. He prescribes Blackness to high modernist aesthetics and rids the cynicism of postmodernist play. Gates doesn’t just transform being but our relationship with it—he transforms our way of seeing.

Theaster Gates: OH, YOU’VE GOT TO COME BACK TO THE CITY is on view at Gray Warehouse through December 20, 2025. Theaster Gates: Unto Thee is on view at the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago through February 22, 2026.