Standouts at the 2025 Performa Biennial

Ayoung Kim: Body^n

“A computer that runs lights. A computer that runs Unity game engine and is fed the motion capture technology. A computer that runs queues. And a computer that runs sound.” This is the technical infrastructure that Ayoung Kim’s Body^n requires for its 40-minute performance, according to one of the technicians. This computational framework allows Kim to push performance into unexplored territories that feel urgent in 2025. It is exciting to see theater, in the broad sense of the word, try on different costumes afforded by advancing software—especially since Kim shrewdly employs her setup to create a multidimensional performance situated in the seam between reality and virtuality.

Body^n is a hybrid performance featuring actors alongside their avatars on two LED screens behind the stage, which is demarcated by a martial arts floor mat. The avatars and their movements are rendered in real time through motion capture technology, and the virtual camera mediating the scenes is operated by a technician using an Xbox controller. The performance follows two “Dancers-Drivers,” the equivalent of delivery drivers, metamorphosed within the apocalyptic virtual world that Kim developed. Like delivery drivers, Dancers-Drivers must transport items from different locations as fast as they can. In Kim’s universe, as in ours, algorithms control, optimize, and drive the platform, facilitating the drivers’ labor, evaluating human performance by impossible-to-meet standards.

Per the program, Body^n is carried out by “professional stunt actors and dancers”—undervalued performers—and concerns itself with “bringing the often unseen labor of performance and stunt work into visibility.” Multiple fight scenes permeate the work, exploring both the choreographic language of stunt performance and offering a poignant critique of the fungibility of laborers, deliverers, and performers so essential to our gig economy.

Much more praise should be given to Kim’s work, but one point of tension must be voiced. Though the performance carefully unravels the exploitation of cultural workers through the metaphor of delivery drivers, its critique seems to obliviously brush over its own invisibilizing of the laborers most necessary for the show: its technicians. Tucked to the side of the immense ground floor of 99 Canal, the technicians hide behind monitors whose screens are illegible to the audience; their labor remains unclear until one investigates what their screens display, which is impossible to do until the show ends. Though the computational infrastructure is not concealed in another room, there seems to be a missed opportunity for a directorial intervention that would sustain the work’s ethos of rendering visible the unseen labor of its own performance. Nonetheless, Body^n offers invaluable insights into what can go wrong in cultural production in a profit-maximizing world.

— Yonatan Eshban-Laderman

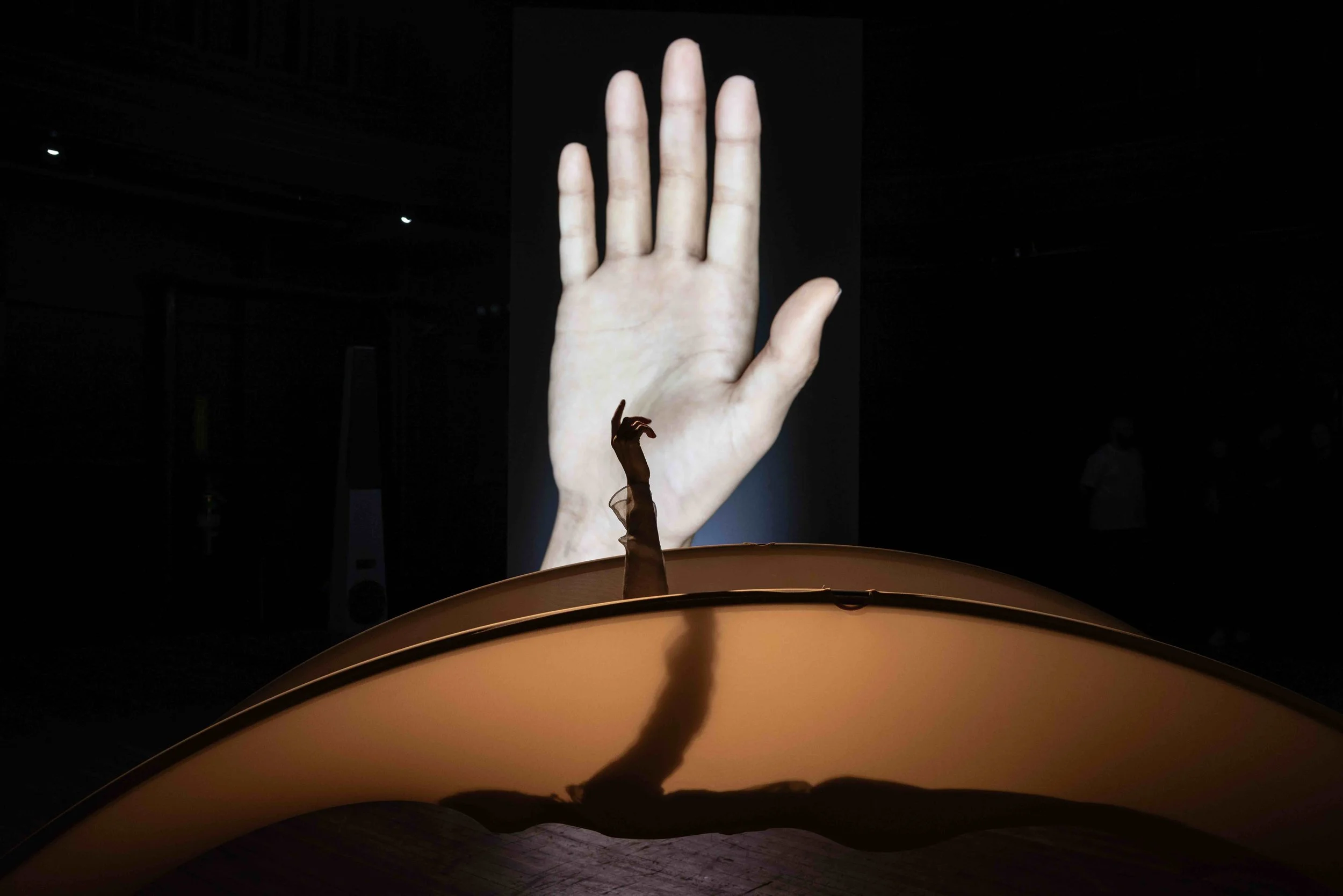

Pakui Hardware: Spores

Pakui Hardware’s Spores begins with a spectacular composition: a baroque-style theater with a balcony, a stage, and a stand holding masks made from what seemed like resin or other transparent yet colorful material; an elongated structure that seems like a hybrid between a flower petal and a coffin wherein the songs’ co-writer and lead performer Justina Mykolaityte reclines with her hand raised upwards; and a formidable screen, probably at least 10ft high, depicting a 3d animated hand that delicately folds and straightens its fingers, mirroring Mykolaityte’s gestures.

The audience is invited to walk around the space while ambient music plays in the background. Mykolaityte delivers an opening, melodic monologue that sets the frame of the performance: “Bear with me / For I’ve never done / Such kind of therapy / Do I speak of dreams and / Childhood memories, / You know, / Like they do / in the movies?” Then, real-time AI-generated text appears on the 3D-animated in response to Mykolaityte’s opening remarks. The performance will ensue the vein of an operatic therapy, which draws influence from classical Greek drama made contemporary to the age of AI and musical theater.

Self-described as a “kaleidoscopic” experience, the performance plants actors in the crowd that turn into a choir who incantates ritualistic hymns, dances, moves around within the space and up to the balcony, carries objects, runs around, and facilitate the backdrop to Mykolaityte’s journey of disalienation.

I was left wondering, however, whether Spores managed to present our relationship to technology holistically. Yes, the performance manages to offer an incisive criticism of how AI increasingly mediates every experience we undergo, to the point that it even serves as our therapist. But the resolution of Spores seems to suggest that only by relinquishing our dependency on technology can we reconcile with ourselves, society, and nature: “Tried digging for companionship / In the depths of the World Wide Web. / My eyes got dry / And thumbs got stiff / Yet all I could see / Was flickering dots / Of millions of solitude.” That throughline is further echoed in Spores’s ending, where the protagonist and the choir leave the “bowels of the city” and “its nanosized rooms” to start “A club of silent mushroom foragers.”

Sadly, that romantic fantasy does not offer a program towards societal transformation where the destructive applications of technology are curbed. It also does not really display the positive affordances of technology, instead committing to a demonizing stance against it. In our contemporary, highly complex socio-technological existence, it does not seem productive to indulge in illusions of simple fixes. Rather, a performance that attempts to insightfully navigate this new terrain we are all rehearsing should strive towards a non-reductive, open-ended grappling with how our lives become increasingly technological and what we can do to ensure that such an inevitable path does not result in our destruction.

— Yonatan Eshban-Laderman

Regina José Galindo: La Fuerza de la Izquierda

Chatter faded into silence. Rallied in the Salon Simón Bolivar at the Americas Society, the audience formed a circle, solemnly awaiting the performance. Regina José Galindo walked down a stairway behind the salon, followed by her co-performers. They breached the circle, regrouped in the center, and stood there until Galindo sluggishly fell backwards into the hands of her colleagues. They gently raised her still body horizontally, using only their left hand. The funeral pose stabilized. Some left their roles, leaving others to carry the burden, yet they orbited closely, prepared to replace anyone in need. After holding the pose for a few minutes, everyone regrouped and lowered Galindo back on her feet. They moved through the salon, reenacted this ritual a second time, and without a word, left back through the stairway.

Guatemalan artist, poet, and activist Regina José Galindo debuted La fuerza de la izquierda (The Strength of the Left) for the Biennial, marking her first performance in the US. It continues her decades-long treatise on the body as a channel and symbol for political protest. This one, however, is less action than poetry: a tribute to the underestimated force of left hands and leftists. Here, the literal uplifting of the body at once functions as eulogy, disobedience to right-wing (right-handed) discipline, and a pledge to collective solidarity. It’s a fragile support system: using both hands—yielding to centrism—seems safer. But Galindo is willing to put her body on the line for the physical and ideological integrity of leftism. Artificial safety never reaches the subaltern anyway.

This is far from her most radical or condemning work, a slight disappointment given its political timing. There’s palpable tension boiling underneath the poetry—discharged only through visceral panting and tremors. Yet symbolism appears too shy to pierce through the commotion, to reach beyond the Americas Society, itself gatekept by RSVPs and privileged artworld etiquette. Perhaps this belonged to public space.

There is, however, intentionality in these limitations. It’s undeniably striking for Galindo to perform at 680 Park Ave, in a historic building owned at different eras by the New York elite, the Chinese Government, and the Soviet Mission, before housing the Americas Society via the Rockefellers. The ghosts of capitalism and socialism co-exist here, just as Galindo’s precarious monuments clash with its illustrious interior. A clash that also extends to New York City’s Upper East Side, an epicenter of American generational wealth itself currently contested by the revival of Democratic Socialism.

This site-specificity likewise manifests in the power dynamic between Galindo and the audience, mediated by the casually clothed co-performers acting as a bridge. Melting the frontier between spectator and spectacle implicates the audience within the architectural design of Galindo’s precarious monument, and by extension, leftist struggle. As a witness, you are thus ethically liable for her safety. If she falls, you too are complicit. Your art viewer status doesn’t absolve you from the guilt of facilitating harm. La fuerza de la izquierda creeps under your skin by asking: how much struggle do you need to watch before you’ll lend a hand?

— Nicolas Poblete

Tau Lewis: No one ascends from the underworld unmarked

Art is no stranger to the cyclical language of metaphysics: the “afterlife” of the object, the “death” of painting, the “resurrection” of sculpture. In Tau Lewis’s newest commission for the 2025 Performa Biennial, No one ascends from the underworld unmarked, the artist carries on her commitment to imbue life into found objects through an operatic rite of alchemic ventriloquism. In other words, the performance centers spirit.

Staged beneath the ribbed vaults of the Harlem Parish, the performance takes its narrative and its epigraphic title from the ancient Sumerian epic The Descent of Inanna (c. 1900–1600 BCE). Under looming spotlights, the story follows the goddess Inanna (voiced by Gelsey Bell) on her voyage to the underworld, the home of her widowed sister, Ereshkigal (voiced by Alicia Hall Moran). Inanna, a bare-breasted sculpture made of recycled, shredded fabrics, is tended by two servants who kneel at her feet. She begins her descent into the curdling blood moon of the underworld, a world bloated with Ereshkigal’s servants who throb and flail.

The composition, developed with composer Lyra Pramuk, guides us through the story in operatic form. Vowels stretch over the hum of a tenor saxophone and the shimmer of brushed cymbals. As Inanna confronts the seven gates of the underworld, she is commanded to rid herself of her adornments: a crown, a lapis necklace, a breastplate, and a robe. Interspersed by booms of theatrical narration and unraveling arias, the score, like Sumerian cuneiform, is vulnerable to disjunctive but hypnotic translation.

In the underworld, Inanna is turned into a corpse by Ereshkigal, who is formed out of a patchwork of leather and suede scraps. Inanna is carried in as a mummified self, embraced by a fabric tarp like a piece of butchered meat. In her wake, Inanna’s humble servants and a pair of mossy creatures cry at multiple sites. They call for Inanna’s discarded ornaments as though they are synthetic extensions of the goddess herself. We find solace in this shared grief: the ways we might, in our most desperate times, mourn the shining pearl of a broken necklace, or the tattered edges of a beloved robe.

Still, we watch the slow burlesque of material death unravel across the runway stage. Like that of Lewis’s sculptural practice, we grieve and celebrate the spiraled life of the object. Both Inanna and Erishkegal’s servants circle and sway around the newly unraveled Inanna, who is now taller and scaled in gold. Held by fluttering melody and sculptural haunting, we follow Inanna’s descent, or rather, ascent into barren worlds in hopes of fruitful futures. Here, spirit becomes its own sculptural material.

— June Kitahara

Robertas Narkus: Shoft Plower

A cryptic voice guided everyone downstairs: “This is not the performance, this is a gate.” Some found the path and the rest followed. Masterminded by interdisciplinary artist Robertas Narkus and designed for the Lithuanian Pavilion of the Performa 2025 Biennial, Shoft Plower was a psychedelic odyssey through the abyss of late-stage capitalism, unearthing the multiplicity of the self and the meaning of human agency in a post-digital world. It unfolded as a scripted, guided performance through the maze-like basement under the Performa Hub. Beyond uncanny, the experience felt extra-dimensional, like drifting into the underworld without warning or explanation.

The voice continued, digitally filtered to sound robotic, decelerated, glitchy. Downstairs, passersby were greeted with an open fridge, revealing a flower bouquet and a piece of foam wearing glasses. Through the studios, there was a TV sprayed with green paint, orb lights, a projection of cryptic graphite drawings, wall-mounted stained photographs of a red fish-like creature, and two co-performers who resembled Narkus, both of whom ignored the intruders. The virtual and the real collapsed as Narkus’s interventions and installations hid in plain sight amidst a mess of art materials, tech, and archives.

Everyone then gathered in an open space around Narkus, who revealed himself as the voice, speaking through a microphone. He wore a VR headset, plunged into a game world set in an office space, which could be witnessed live through a TV screen. Narkus was trying to find someone to hire while trapped in a maze of automated tasks and systems. He drifted in and out of the virtual world to grab physical objects in the basement, but never quite found what he was looking for—or sometimes forgot what that was. Further fracturing reality were fragmented digital projections, otherworldly installations, and Narkus’s doppelgangers who roamed through the crowd like spectral automatons.

For the remainder of Shoft Plower, Narkus and his doppelgangers shared scripted yet seemingly stream-of-consciousness speeches about identity, human agency, and AI, accompanied by an atmospheric black metal soundscape. Everything converged in a dark corner, where guitarist Ted Noser performed a song about power obsession. The song ended, and it was over.

“Every time you make it more comprehensible, you make it less powerful,” said Narkus halfway through. Hence, interpretation feels like betrayal, but it’s still worth noting some of the ideas and anxieties occupying Shoft Plower: self-optimization, over-productivity through automation, work alienation, endless bureaucracy, the existential ramifications of transhumanism, and the dystopia of technological singularity. Part of that was veiled under irony and dark humor, but sincerity came through by the end of the voyage. In harmony, we all listened to Noser as if watching the last sunset before the apocalypse—terrified, but not alone.

— Nicolas Poblete

Lina Lapelytė: The Speech

Through the haze that rises to the dramatic vaulted roof of a neo-Gothic church, children start to appear. We soon realize that they are not human, but animals, with faces bearing an occasional splotch or smear of congealed paint. Each of them embodies a specific creature and coos, caws, snarls, or screeches accordingly.

The performers drag carpet fragments from heaps at the edge of a chalk-lined circle, piecing them together to form the world they will inhabit. This is an elemental, primordial world. Light falls. Night falls. In a quiet scene, the children re-enter as humming bees that spin, swarm, then slumber upon the green-and-beige carpet. Later, they create a stampede that rumbles through the audience, who are mostly seated on the floor surrounding the performance area.

Part of Performa’s spotlight on Lithuanian artists, The Speech is a commissioned work by Lina Lapelytė that features students aged 7 to 18 from Poly Prep, a private school in Brooklyn. (On each of the three nights, a different set of 90 children takes the stage.) Rehearsals were largely led by lower school dance teacher Courtney Cooke, particularly before Lapelytė flew in to join them.

Originally meant to be staged at the Federal Hall memorial in Lower Manhattan, the show was relocated to Harlem Parish and its premiere pushed back due to the record-breaking government shutdown. No matter the barrier, it seems, the human urge to be heard finds a way through.

Whereas Federal Hall, an imposing symbol of democracy, would have given the work an air of dissent amid a climate of rising censorship, Harlem Parish frames it as a reprieve from the flood of talk, text, and information that characterizes modern life. Within this sanctuary, we are set free from the weight of words and the pressure of their politics. Here, children exude purity laced with primal energy, and they communicate simply to cue and to connect. In one adorable instance, a performer gently coaxes his younger colleague back into the whirling throng of wildlife.

Even in past creations, Lapelytė has revelled in the democratic blending of amateurs and professionals. The Mutes in 2022 showcased an untrained choir. Sun & Sea, the indoor beach opera she cocreated that won the Golden Lion at the 2019 Venice Biennale, had singers intermingling with locally cast beachgoers. Similarly, in The Speech, Lapelytė presents a level playing field, a human mass with no protruding heroes or villains, a work of art that offers access and invites participation.

The piece feels unfinished; its duration, initially advertised as an hour, has been cut by more than half. This is not entirely a surprise, given Performa’s experimental mandate, and perhaps the abrupt ending is a fitting one. The children, having all turned into apes, race along the periphery of the audience, yelping and yelling. They exit and congregate at some unseen spot. The hair-raising cries of the mob grow louder and louder, then cut to chilling silence. What happens, we wonder, after language emerges, after humans overrun the earth, after the children we saw grow into adults? For now, we can merely reciprocate nonverbally—with claps and hoots and whoops.

— Fred Voon