Reflections on Proximity

Most of us carry around a few thousand images in our pockets every day, and that’s not even counting the additional trove endlessly filed into online platforms, accessible via only a few swipes. Still more images greet us—on public transportation, billboards, publications—and others still are tucked away in photo albums and containers, stacked in shoeboxes at vintage stores for the shoppers’ perusal, and preserved in library flat files under slick, archival sleeves.

At a certain point in my conversation with Leslie Hewitt, after discussing recent works and her philosophies in the studio, I asked the artist her thoughts on this widespread practice of what has become personal image accumulation on an unprecedented scale. Pensive yet playful, Hewitt responded, “It proves that we can’t remember very much. We use it as a mediating tool. The less insidious part is its role in memory and personal archive. The more insidious part is that we’re all practicing some level of self-surveillance. There’s a layer in my work that resists that aspect of the camera. It points to things but does not exactly reveal them. I’m asking, ‘Is proximity enough?’”

This question is palpable throughout Hewitt’s work, not only in the measured layering and combining of images, but through the artist’s intention to consider the choreography of the viewer, when they might be drawn closer or hang back. Her first aesthetic interest was dance, and she is prone to considering the sensory and spatial effects of her work. In ongoing collaborations with her partner, artist Jamal Cyrus, Hewitt experiments with dance and sculpture alongside Cyrus’ music and composition. This type of collaboration has become an essential facet of her practice; in Soft Tremulous Light at Perrotin, In Collaboration with Jamal Cyrus, Rhombus or Humming Song (I-IV-V) (2025) hangs canvas-like, tempting us to touch its tambourine cymbals, and throughout the exhibition, Hewitt considers Marc Augé’s supermodernity in partnership with writer and scholar Elleza Kelley.

Kelley’s supplemental text, Angles of a Landscape, offers new language to Hewitt’s interests: “I am drawn to this delicate, purposeful line that appears at the point where memory image meets surface and then meets something that slips identification and categorization. This subtle geometry conjures the mise-en-scène of doors, windows, portals, places for escape.” Hewitt is similarly interested in the boundary between analysis and memory, constructing works that intentionally reveal the multiplicity of supposed certainties.

Befittingly, Hewitt’s Achromatic Scales, currently on view at the Norton Museum of Art, presents multiple series in conversation. The works of her series Riffs on Real Time (2012–2017) are gelatin prints, documentation of layered color photographs compressed into black and white by the lens. Here, as elsewhere, the camera is employed as a tool to document Hewitt’s sculptural acts.

In selecting images for the series, Hewitt looks to vernacular photography. “I see it as the most literary, a space of opening. The pressure on the photographer is not to capture in the sense of a journalist. It’s a happenstance image,” she tells me. Hewitt is drawn to the unexpected elements that inevitably appear in these photographs, teasing out what is strange or unique by placing images in conversation. Various pairings and arrangements offer different suggestions as to what an image might convey. We are invited to be discerning, to examine the familiarities alongside the uncanny, and make a critical analysis.

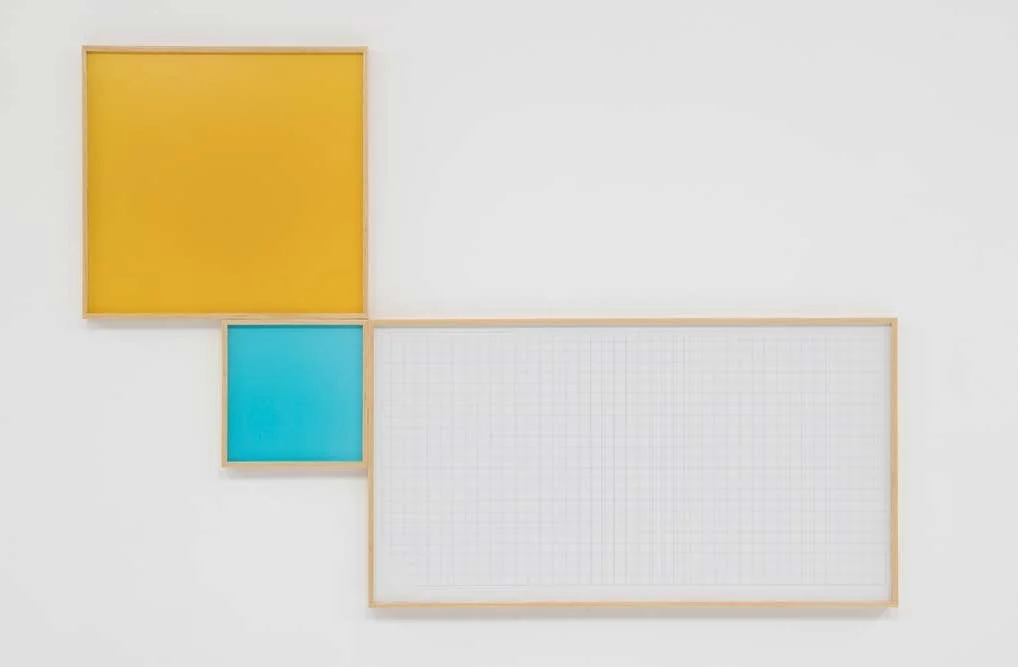

The series Chromatic Grounds (2018–) prioritizes the influence of color on the eye and mind. Following the black and white image-making of Riffs, Hewitt began to consider how to further slow the viewing experience, thinking about how color operates as light. The following works distill color as atmosphere, made by manipulating calibrated colored light and photosensitive paper. As the hues register, we may be transported to another time or place, or observe an abstract feeling otherwise inexpressible. Throughout Achromatic Scales, the works of Riffs are positioned in direct conversation with these color fields, suggesting opaque narratives and sensations that we are continuously invited to uncover.

The architectonics of these presentations are another developing consideration; at the Norton, a leaning wall completes the framed arrangements in a three-dimensional interruption. As I found my way through the Perrotin exhibition, I was drawn to works non-linearly, distinctly aware of my height and vantage point as I circled the adorned boulder called Birthmark (2022). Hewitt is currently developing new ways of sculpture-making, considering gestures in relation to pure objects and experimenting with processes.

When I prompted Hewitt to present a thesis or throughline for these recent bodies of work, she cited consistency. Time passes, the world changes, and bullishly consistent work offers a helpful friction. Despite what the constant pressures of making art in the year 2025 may suggest, what is made need not be strikingly new. In fact, as time seems to pass more and more rapidly, and as we are bombarded with continuous imagery, making work that does not prioritize the new becomes an act unexpectedly subversive. There is great discipline in returning again and again to what an aloof observer might dismiss after first inspection. This way of working reflects an alternative set of values; among them, repetition, collaboration, and exchange.

Leslie Hewitt: Achromatic Scales is on view at the Norton Museum of Art through February 22, 2026.