Reflections from the Screen

The depth of pop-culture subject matter can be deceptive; when reproducing images that are already so recognizable on their own, they run the risk of being received as kitsch or nostalgic. Alien Queen / Strange Paradise at the Museo Tamayo in Mexico City faces that challenge, but ultimately, a deeper through-line between image-making, trans identity, and the ritual of painting emerges. Berlin-based, Mexico City-born painter Manuela Solano’s exhibition features TV characters, personas, and celebrities recognizable yet distant, allowing the viewer’s own identity construction to enter into dialogue.

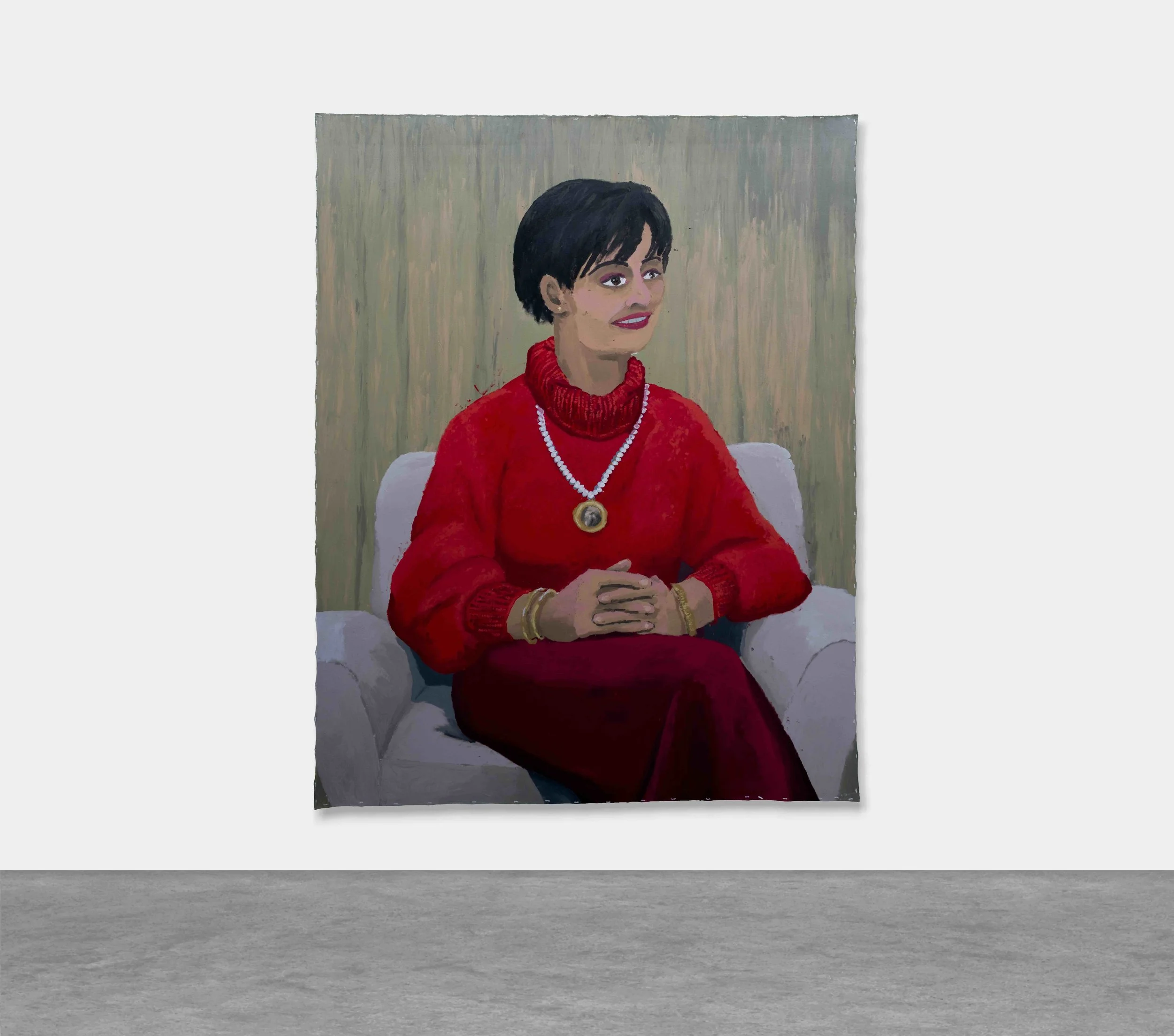

Solano’s portraits are not of people, but of screens. The portraits are the product of a double lens, first through the TV-camera projected onto the screen, and then from the screen projected onto the canvas. This freezes the image, producing a dead-eyed quality in the sitters: the figures become dolls, and the screens act as mirrors. One attribute that causes this phenomenon is the clasped-hand pose that many of the figures are styled in. Sheela (2022) is a portrait of a woman, Ma Anand Sheela, who stars in the Netflix docuseries Wild Wild Country (2018) about the Rajneeshpuram, a cult led by the Indian spiritual leader Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. In Solano’s portrait of Sheela, her hands are clasped, and her eyes are unfocused and frozen; the posture, hand gesture, and setting of the figure feel staged. Sheela is flanked by Frieza (2024) from Dragon Ball Z and Marge (2024) from The Simpsons, who hold their hands in similar poses.

Images, and especially ones from pop culture, have an ability to communicate an aura that literature might fossilize. The figures in Solano’s works are not selected to represent themselves, but instead for their cultural symbolism. They are images that tile together her identity: an artist, a trans woman, a club-goer, a blind person living with HIV, a lover, a human. Solano thinks of these works as self-portraits, but also images that the audience can empathize with as well: through the distance produced by the screen, the figures become empty vessels onto which the viewer can project their own images.

Solano’s choice of subject matter recalls the type of avatar-building that gender-nonconforming people are quite conscious of. Trans people use the concept of the avatar to reconstruct their gender presentation from a collage of quotidian icons, images, and experiences. But developing an identity based on surrounding culture and symbols is not exclusive to trans people, nor is it exclusive to the development of sexuality or gender. Humans are a mimetic species; reflection is fundamental to the way we think, learn, and understand ourselves.

Alien Queen’s first impression is fun, but paint-deep. This is perhaps exacerbated by the tug-of-war between the public’s hyperfocus on Solano’s blindness and the painter’s own efforts to mitigate this. Reception of Solano’s work is at times over-celebratory towards the artist’s identity as a trans, HIV+, and blind painter, which might shroud the significance of the work (which the artist certainly considers). Despite the astoundingly little time people spend looking at an artwork [1], paintings shouldn’t necessarily give themselves away immediately, and something rewarding is to be found when you sit with Solano’s work.

While I run the risk of also paying too much tribute to Solano’s vision loss, the idea of a painter going blind and continuing to paint felt like a salient testament to the human need to produce images. During a lecture she gave at SOMA in Mexico City, Solano spoke on a previous exhibition of imagined interior scenes, which deepened my understanding of Alien Queen / Strange Paradise. Solano describes interior spaces as having distinct personalities which inhabitants adopt, and by externalizing the visually constructed architectures onto the canvas, the artist communicates a feeling to the viewer so that they too can experience. Both series grasp at a feeling that is fleeting, shifting, or just out of reach. And while the artist emphasizes that the works aren’t about nostalgia, it feels impossible for nostalgia to be absent from them.

Manuela Solano: Alien Queen / Strange Paradise is on view at Museo Tamayo from October 9, 2025 through January 4, 2026.

[1] Lisa F. Smith, Jeffrey K. Smith, and Pablo P. L. Tinio, “Time spent viewing art and reading labels,” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 11, no. 1 (February 2017): 77–85.