Violence Upended

The moment I stepped into Jay Payton’s solo exhibition, The Cruel and Violent Nature of Domesticated Homo Sapiens at 15 Orient, I was enthralled. The technical precision, depth, and saturated hues hit at once. That jolt of recognition, the instant pull, was something I hadn’t felt since Jack Whitten’s retrospective at the MoMA. Payton’s work exists between collapse and renewal—something dying and something clawing its way back. The tension between the paintings feels alive, almost restless. Payton’s work may unsettle, but that unease, tempered by his controlled yet daring use of material, is what gives the paintings their charge.

Throughout his work, thick layers of oil paint, sticky unnameable substances, wax, and found objects like razors, circuit boards, and lipstick pigment form surfaces that are scorched and tender. Jhator “Giving Alms to the Birds” (quadriptych) (2025) is built like an asymmetrical grid stitching together fire, soil, fog, and ice. Black burns into red; red collapses into cataclysmic splashes of orange. The smaller canvases in the grid feel hopeful. A rhythm of repair forms as each composition becomes its own atmosphere: one fog, one tundra, one forest floor. Alive in their undoing, Payton’s paintings build conditions in which meaning begins to fail, matter resists containment, and something new takes shape.

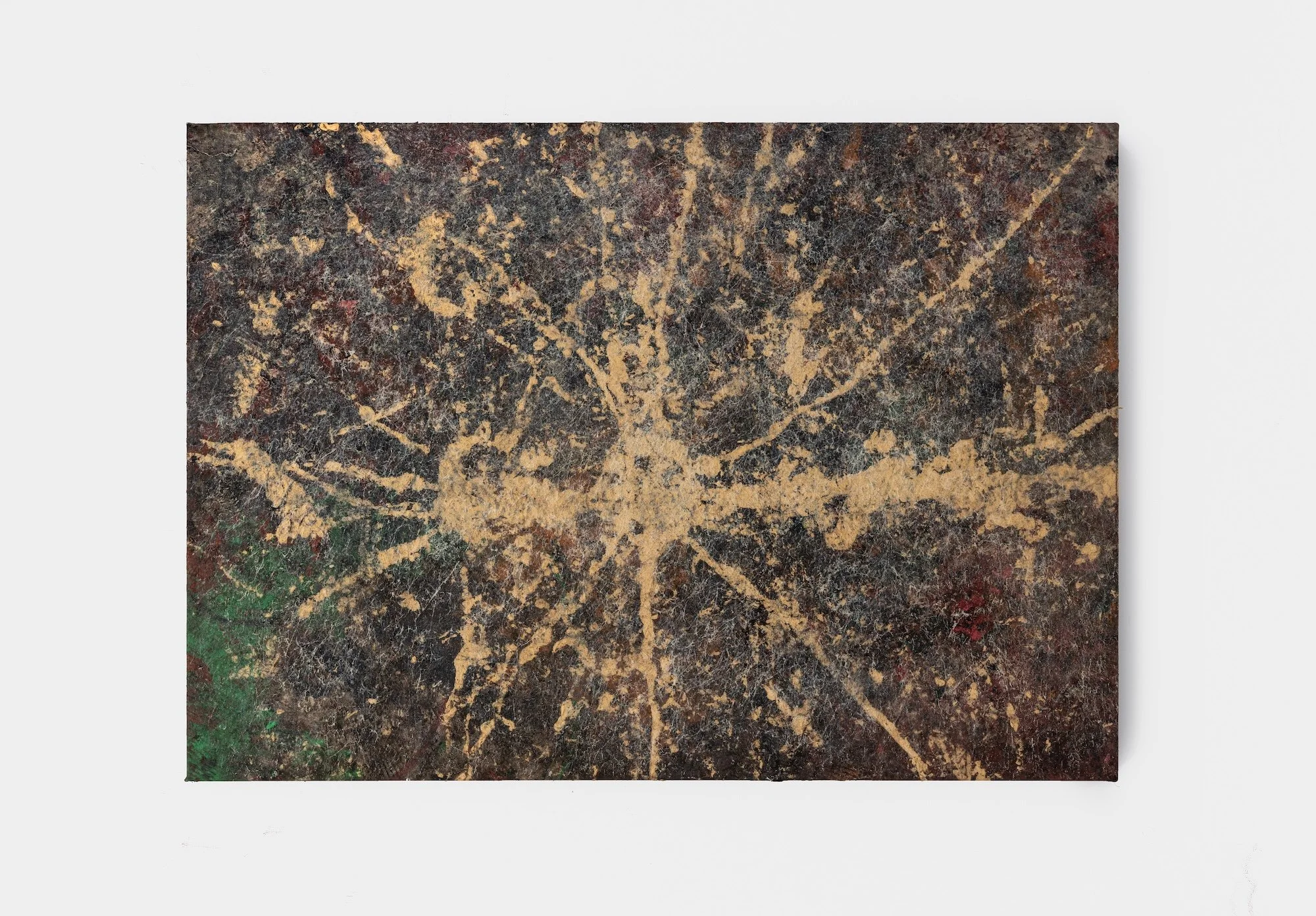

Sign and signifier, as well as linguistic meditation, are important to Payton, as evident in his titles like The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner by Randall Jarrell, which references the historic poem. There is also a text written by the artist, titled Violence, that considers humanity’s innate violence, familial relationships, and evolution’s capability to upend violence once and for all. BEWARE OF THE NUCLEAR WEAPON! (2025) takes us there as black and muddied hues of reddish brown layer upon themselves. A sulphuric earth tone sprawls from the center, fissuring across the canvas. It’s unearthing something: a bruised green edges the lower corner like moss, while subtle hints of blood red bubble to the surface. In this painting and others, Payton utilizes a white spray adhesive that creates cohesion within worlds that are upending. Flirting with the viewer, it lies delicately over the crevices and valleys of built-up oil paint, drawing everything together.

Though not imitative, there are moments when Payton’s language feels tethered to the masters he clearly reveres. The chromatic heat and gestural layering recall Jack Whitten, Sam Gilliam, and even Alberto Burri. Though he draws on these historical predecessors, Payton’s command of composition and color temperature remains uniquely captivating. Considering that every work in the exhibition was completed in 2025, it feels inevitable that his visual language will continue to expand. That inevitability keeps Payton at the top of many watchlists.

Kinbaku-bi 緊縛美, Bite the Curb, and If you hold a gun… each introduce figuration and found imagery into a show otherwise grounded in abstraction. Astutely, 15 Orient places If you hold a gun... as the first piece viewers encounter upon entering the gallery. The placement affirms Payton’s approach to investigating assemblage and figuration as equal contenders to the use of abstraction. Circuit boards, a reference to the infrastructures of communication and power, double as a quiet indictment. At their root lies the material violence of extraction: cobalt and coltan mined under brutal conditions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. These minerals make our networks possible, their extraction a quiet violence embedded in the devices we hold. By integrating these fragments into his composition, Payton collapses the distance between technological progress and human cost.

On the opposite half of this artwork, a stark triad appears: the cover of TIME featuring eleven-year-old Robert “Yummy” Sandifer above the headline “So Young To Kill, So Young to Die,” a set of teeth, and a colonial-era photograph of a Belgian officer smirking in the pleasure of the torture of a Congolese boy whose arm was amputated as “punishment.” The juxtaposition forces a confrontation with how Black suffering circulates through history’s visual economy.

Payton dissects violence with rigor. Brutality becomes image, image becomes memory, and memory calcifies into myth. Kinbaku-bi 緊縛美 and Bite the Curb integrate Payton’s abstract language more evenly. Imagery becomes more deeply embedded in the accumulation of surface textures. The surfaces still operate through wax, adhesive, and pigment, but meaning accrues through historical imagery and other objects, such as razor blades.

Through figuration, Payton clarifies the stakes of abstraction. The exhibition exposes the metabolic root of what Payton has been engaging with all along—that violence is at our root, but it doesn’t have to be. His paintings insist that collapse is not an ending but rather a threshold of awakening. Leaving 15 Orient, I kept thinking about that enigmatic pulse of survival; it’s what pulsates in Payton’s work. Ruin and renewal keep trading places, daring us to see which one we’ll choose next.

Jay Payton: The Cruel and Violent Nature of Domesticated Homo Sapiens is on view at 15 Orient from October 30 through December 6, 2025.