An Ode to Waste

Artists, at least those with a material practice, inevitably insert themselves into the cycle of our predominantly linear economy: extraction, production, exchange, consumption, and waste. Despite art’s strange status in a capitalist economy—given its aesthetic function, which could be deemed privileged—art is not shielded from the marketplace, especially when the artist aims to make a living from their practice. As such, the creative act is not exempt from an analysis that considers the consequences of creating an object that eventually becomes waste, even if it is sold: another blob of matter in our overaccumulated world. Some artists, however, choose to reverse this cycle. With an awareness of the excess excreted by consumerism, their practice begins with waste, with found objects, with materials others have discarded. As the saying goes, one man’s trash is another man’s treasure.

In her MFA thesis, Rosalie Smith compares the artist to a digestive tract. She writes, “I contend that, just as food is consumed, digested, and expelled from the body, artists absorb experiences and perceptions—process them—and ultimately defecate them in novel interpretation.”[1] Smith identifies as a “found object artist” invested in “assembling and transforming discarded materials en masse.”[2] She describes her process of collecting waste as “passive.” She does not actively seek out her objects, but rather lives her life and collects trash that crosses her path.

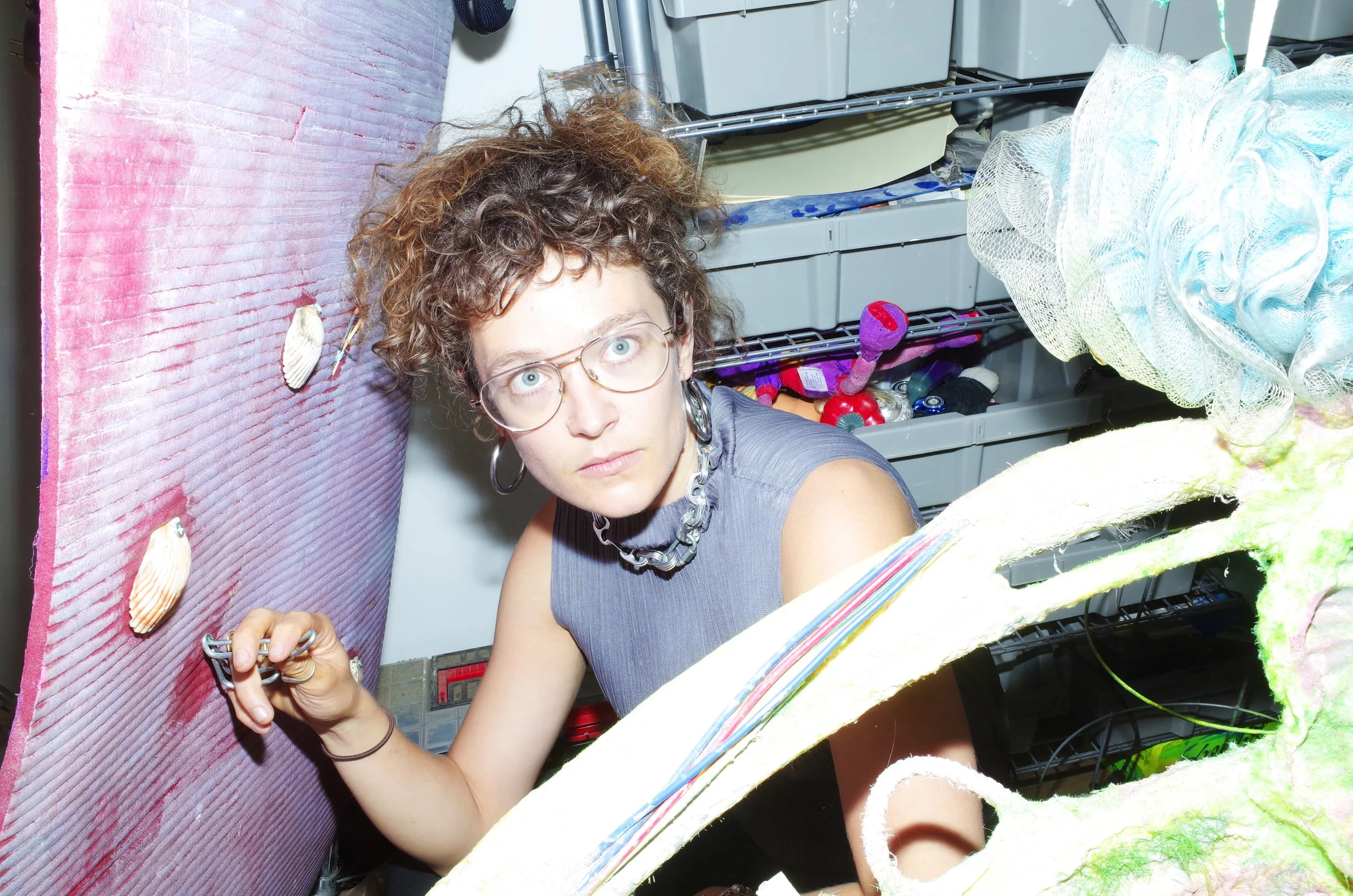

The diversity of products Smith finds through casual foraging in the streets—and the sculptures she creates from them—is truly incredible. Visiting her studio, I felt as if I had entered a post-apocalyptic amusement park. I inquired about a formidable structure hanging from the ceiling: a circular floating form, similar to how we popularly imagine a habitable space station, with what appeared like mold growing on its surface. Smith replied, “Oh, this is a fruit rack from a bodega that I flipped.” I was surprised, to say the least.

Throughout her studio, Smith has objects that pervade our daily experience: golf clubs, stroller parts, an IV stand, buoys, BuzzBallz, car parts, a TV antenna, a Papasan chair, a bar stool, shoes, racks. And yet these items become barely recognizable in her sculptures. Smith’s medium descriptions become sites of revelation—rendering the components of each sculpture explicit while simultaneously attesting to how much each piece hides its material economy. Like an alchemist, Smith indexes both the potential harbored in our everyday surroundings and the haunting question hidden in our waste: Do we really throw all of these things away?

But Smith is not interested in merely lingering with the false promises of our present. In other words, Smith’s critique of our wasteful economy is not limited to aesthetically repurposing trash. Rather, her work is an archaeology of a future where waste conquers human life and merges with it. To quote Smith’s thesis again: “Inspired by the notions of microplastics and the singularity, I am imagining a world in which our bodies have devolved into cancerous growths upon material waste, merging with plant life and technology.”[3] Ziptyng, gluing, plastering, drilling, wrapping, and tying materials together, Smith recovers worlds thrown away by their previous owners and resurrects them for an afterlife in an alternative future where they voice the stories they hold in potential.

Here, Smith’s piece Marriage Bed and Breathing Tube Support Station (2025) comes to mind—a sculpture depicting a dying pile of grass flock and debris on a structure looking like a hospital bed, actually made of a beach chaise connected to a filing cart holding a respirator. It is unclear whether the grass flock is a body decayed on the Frankensteinian hospital bed, or whether the hospital bed grew tumors resembling a body from all the waste it accumulated, like the game controllers protruding out of the grass flock. Intimately folded within this material and conceptual tension, however, is also a story of love, death, and, as the titular phrase marriage bed suggests, of transition between one state, or world, to another.

Smith’s exploration of the indeterminate space opened up by material bequeathed to the streets by others recurs throughout her body of work. At its core, Smith’s practice negotiates the appropriation of the inherited material world, the wake of objects left by the constantly circulating urban landscape in which she lives—or, to invoke what Jacques Rancière calls the unrepresentable: the impossibility of enunciating one’s unique experience with a language one has not invented.[4]

What Smith proposes, however, is a reconsideration of this equation. We are born into a world of material, or language, that predates us and is beyond our control. Within her constellation, we do not participate in the material world by virtue of reinventing material or language. Rather, she restructures the prescribed language through the specific choices she employs in joining found objects. Smith’s joinery—which manifests as myriad and idiosyncratic techniques in each of her sculptures—is the alchemical gesture through which distinct objects become what Smith deems a “new presence.”[5]

Notably, Smith’s joints are not hidden. Rather, Smith celebrates the wires, plaster, pipe cleaners, and other objects she uses as the connective tissues between the materials she finds. Thus, Smith’s “new presence” does not hide its precarious stature. On the contrary, it lingers on the effort invested in making two different materials touch, thereby advancing a logic of contact that is beyond the notion of linear economy this essay started with.

Interaction, in the field of linear economy, is qualified by a zero-sum logic of transaction: investing energy and extracting profit. An illustrative scenario is what unfolds after a warm hand touches a cold piece of metal. Read alongside the logic of transaction, this scene describes the moment in which the hand lost its warmth to the cold metal. Or, focusing on the metal, the moment in which the cold metal warmed up from the hand that lost its heat. Smith’s joinery, however, diagrams a way out of this zero-sum logic.

Foregrounding the site of touch between two objects, Smith’s joinery freezes the transaction at the act of exchange. Sociality is required for transaction, but under capitalism, it is erased by the importance placed on the gain and loss of capital. Her decision to focus on the interconnectedness between object/subject illuminates the community we are part of, unearthing the knots, networks, wires, zipties, and pipe cleaners that link us.

Smith references the sociality her practice depends on in a story she recounts in her MFA thesis. She describes how “green BuzzBallz [were] a recurring motif” in her sculptures, almost all of them collected at the intersection of Church and Canal Street in Tribeca. As a result, Smith deduced “that there is someone regularly hanging out on that corner that is particularly fond of green BuzzBallzs, above all flavors.” She continues to describe this encounter with the stranger as a “symbiosis with this unknown person” who enables her to “harvest the radioactive waste-tinted shells of their happy hour.”[6]

Staying with the moment two discarded materials are connecting—or two discarded people, at the intersection of Church and Canal Street—is the gift Smith bestows to the viewer. In the age of digital isolation, Smith’s practice offers a reminder of our entanglement: if by nothing else, we are bound together by our intersecting wakes of material excess.

Rosalie Smith currently features works in The End at Spielzeug, Baker’s Dozen at Torrance Art Museum, and Mary’s Room at nuun gallery.

[1] Rosalie GL Smith, “The Logic of Car Accidents and Other Digestive Processes” (MFA thesis, CUNY—Hunter College, 2025), 1.

[2] Smith, “The Logic of Car Accidents,” 7.

[3] Smith, 13.

[4] Jacques Rancière, The Future of the Image (Verso Books, 2019).

[5] Smith, 10.

[6] Smith, 8.