Preslav Kostov: “Soft Focus” at Tara Downs

An oft-mentioned painting in Ben Lerner’s novel 10:04 is Jules Bastien-Lepage’s Joan of Arc from 1879. At one point, Lerner’s narrator makes note of a museum placard (the painting is on display at the Met), which describes attacks on Bastien-Lepage’s failure to reconcile the realism of Joan’s figure with the ethereal bodies of the angels suspended behind her. The perceived flaw, however, is the narrator’s favorite aspect of the painting, for as the background obscures—or “swallows”—her fingers, the tension between physical and metaphysical “produces a glitch in the pictorial matrix.” It’s as if in being called to battle, Joan really must come to trade the naturalism of the material world for the register of the elemental and symbolic. We’ve caught her in a moment of transition.

I thought of this when looking at Preslav Kostov’s paintings, on view in Soft Focus at Tara Downs. The limbs of bodies recede into their backgrounds, the edges of wrists and ankles and necks swallowed by the sky-like assemblages against which the forms are set. It’s not so much a pictorial glitch, though, as it might be an obfuscation of the origin and border that constitute a human body. The figures seem to come from somewhere and some time, emerging from loose oases behind them, with pale skin as if just born, but the adulthood and exalted character implied in their figures bring them into a more Elysian register.

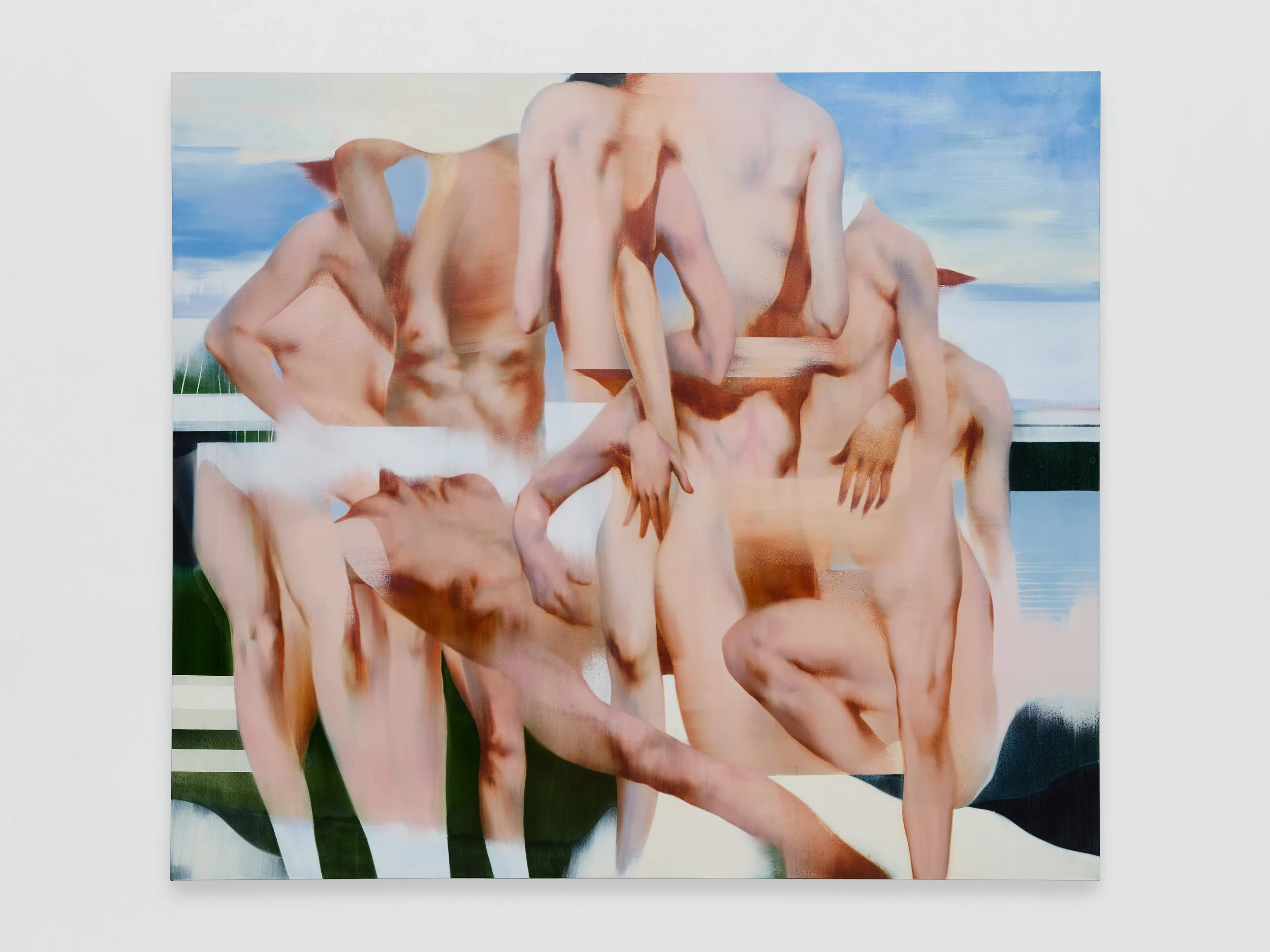

This is not to say that there aren’t “glitches,” so to speak—in Rush (2025), one might think to peer into the more jarring segments of white and wine-dark sea, layers of depth behind the figures. In Out of Town (2025), the thin, dripping streaks run in paradoxically horizontal lines, bringing the edges of legs along with them. In Trust fall (2025) and Facade (2025), translucent panels interrupt the continuity of scenes, like screens in between bodies. The acetone mixture Kostov applies to still-wet paint produces an effect akin to rust or the irrevocable decay of analog film; stretches of cellular dissolution perforate the otherwise ethereal contour of muscle and shape.

For all the hands that appear in Kostov’s paintings, there’s a surprising anti-haptic register, as if the sensations these bodies might experience are inaccessible to viewers or elevated above mere stimuli. That all the paintings depict collections of bodies implies a kind of group portrait, but while they seem to collide and intertwine, they also seem not to quite touch, meeting on a plane indebted to time and space but belonging to a more delicate sense of proximity and exposure.

Then there’s a painting like Parade (Masstige Paradise) (2025), more starkly segmented into quadrants and with more crisp distinction between forms. In this echo of photomontage, the bodies are caught in different shades, occupying disparate moments in time in a day, in history. In some, the scale of each figure is distinct, a magnified torso proximate to a smaller head. Do they know each other? The degree of their contact is elusive, even as the gestures of hands and limbs often suggest intimacy and eros. At times, a painting can seem to capture a single body—both a particular and an ideal—in successive motion, akin to multiple exposure or a transposed futurism. Rush is like this, in which the figures seem to fan out from each other, caught at stages of evolutionary development and culminating in a kind of final form.

And yet there is no finished body, really, in Kostov’s paintings; each synecdochic form lacks at least some parts of an imagined whole, a head or feet perhaps, and each seems to imply the necessity of the others which surround it, a bouquet of figuration. The effect is a kind of collectivity in both space and time: rarely do the bodies face each other directly, so perhaps their embrace is unbeknownst even to them, but they are illuminated by their physical affinity, like reprisals out of the water.

The providence of their encounters is key to the disfigurement that allows them to intertwine. Now, disfiguration is often associated with generative AI programs, notoriously bad at rendering an anatomically accurate human body—hands, it seems, are a particular challenge. (Hito Steyerl has compared Stable Diffusion’s chimeric outputs to the bestiary, monstrous figures of pre-Enlightenment visual culture.[1]) Disfigured entanglements painted by other artists like George Ruoy or Ambera Wellman have drawn light analogies to such kinds of artificial images in invocations of cursory likenesses between an array of surreal, distorted forms that populate the internet as well as figurative painting. It’s not dissimilar, too, to other medium comparisons: the way that Jack Whitten’s use of a two-by-four to drag paint across canvas, for instance, gets compared to photographic blur.

This particular read often implies the necessity of setting, as if the swirling and discordant non-place behind a disfigured body rendered in oil might be analogous to the “internet unconscious” from which image generators articulate more legible, though still aberrant, figures. It’s a parochial read writ large, and might be especially reductive applied to Koslov’s work. The figures are reminiscent both of classical sculpted torsos and the more vivid contours by someone like Lucian Freud, but it’s their contact, their simultaneous excess and lack (and not a creative perversion of training data), which lends them a form. There’s a kind of irony, then, to Kostov’s paintings, in which pale pink nudes, a hue in between cherub and man, collapse into heaps of flesh. Even as limbs fade into thick streaks, the figures insist on the human body as both origin and product of the world they inhabit—a light, self-aware anthropomorphism that, too, dissolves into inhuman extensions and ambivalent hues.

In Facade, a body is crouched, his head burrowed in the chest of a more feminine figure to his right. They may or may not be sharing in this coastal background, with its ominous storm and seeping precipitation—a celestial beach, a primordial horizon. Limbs that cannot anatomically belong to either figure emerge from the crevices between the two more fully formed bodies. His shoulder is raised, turned to protect his neck, his hand outstretched in defense and obscuration of his face. And then there is the ear, rendered in sharper detail amidst the hazy streaks of leg and pronounced decay of the acetone-treated canvas. In Trust fall, too, the ensnared churn of forms also gives way to an ear, the head from which it protrudes turned sideways, hidden. In both paintings, the ear is exposed while the body is obscured.

This concentration of detail occurs in other paintings as well, in the meticulous shading on a nipple and the underside of a foot, or the contours of a hand (the careful rendering of knuckles at which Stable Diffusion fails). But between the eight paintings on display, there are no eyes or noses or mouths; the ear is the closest a viewer might get to an orifice, an implication of sensory experience. They’re surprising at times, these openings into the imaginary register of the painting. Viewers never quite see the body whole, instead accessing the body as embedded in forms both similar and not, human and less so. Perhaps there’s a glitch in there, too.

Preslav Kostov: Soft Focus is on view at Tara Downs from September 5 through October 25, 2025.

[1] Hito Steyerl, Medium Hot: Images in the Age of Heat (Verso, 2025), 59. See online chapter here.