On Digital Sensation and Rotting

I. The Art of the Future

In August of 2024, I worked in the studio of Dennis Rudolph, a Berlin-based artist. On my first day, I arrived at his studio: a gutted apartment with jagged lines in its ceiling where walls once stood. The room was, at times, peculiar. In its center, just behind a leather chaise lounge, sat the toilet, completely exposed. When one of us had to use it, the other would wait in the hallway until a flush could be heard.

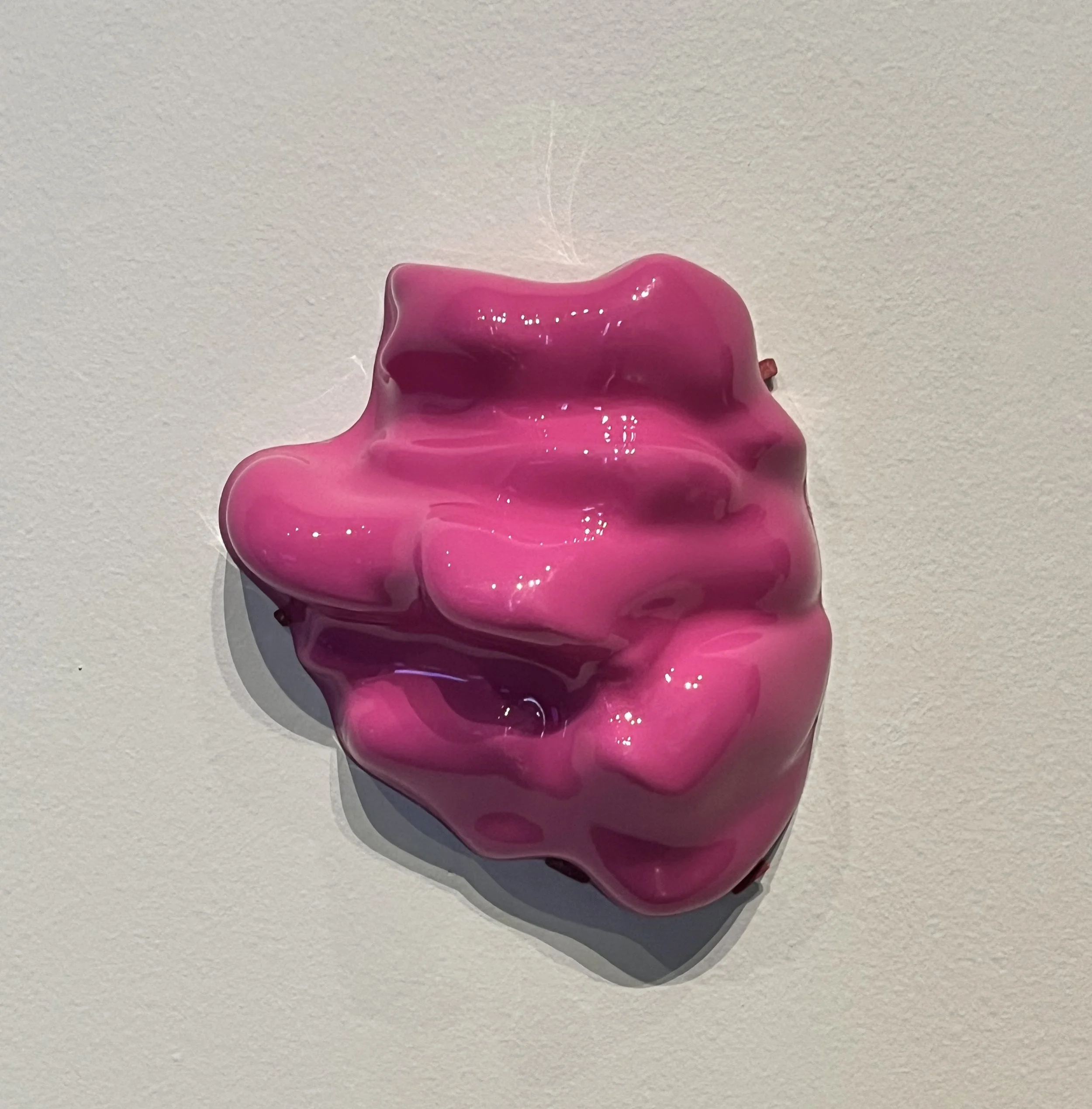

To the right of the chaise lounge, Dennis had propped a 3D printer atop a pedestal. In operation 24/7, the device faintly screeched as we completed other projects. Every so often, my attention would drift to this constant noise, reminding me that digital data was slowly taking a material form.

Midway through August, the screeching stopped. Dennis’s project had finished printing, and he excitedly extracted a mass of icy blue plastic from the printer’s platform. My task for the day was to clean up the print by detaching the tubular supports surrounding it. The assignment felt archaeological. As I picked away at computer-generated plastic with tweezers, a face began to emerge. Finally, after a bit of tinkering, a geometricized fragment of a bust, set at an angle as though it had glitched through and bisected the floor, sat before me. The digital had become fully physical, appearing to rise into my plane of existence.

On slower days in the studio, Dennis would compose immersive installations on his Oculus Rift, a virtual reality headset. As I sat on the chaise lounge and checked items off my to-do list, Dennis would stand next to me while painting sprawling digital worlds. When Dennis got stuck or encountered an error, he called me in to help. Turning on YouTube tutorials for his VR drawing application, I would walk him through the software.

Our bodies became intermediary vessels for a somewhat absurd conversation between our two devices. The computer on my lap would feed me instructions, recorded on YouTube by a distant stranger, which I would then verbalize to Dennis, still in his digital world. This strange act of translation was like a game of Telephone. Neither of us could visualize the content on the other’s device, which made miscommunication frequent and inevitable.

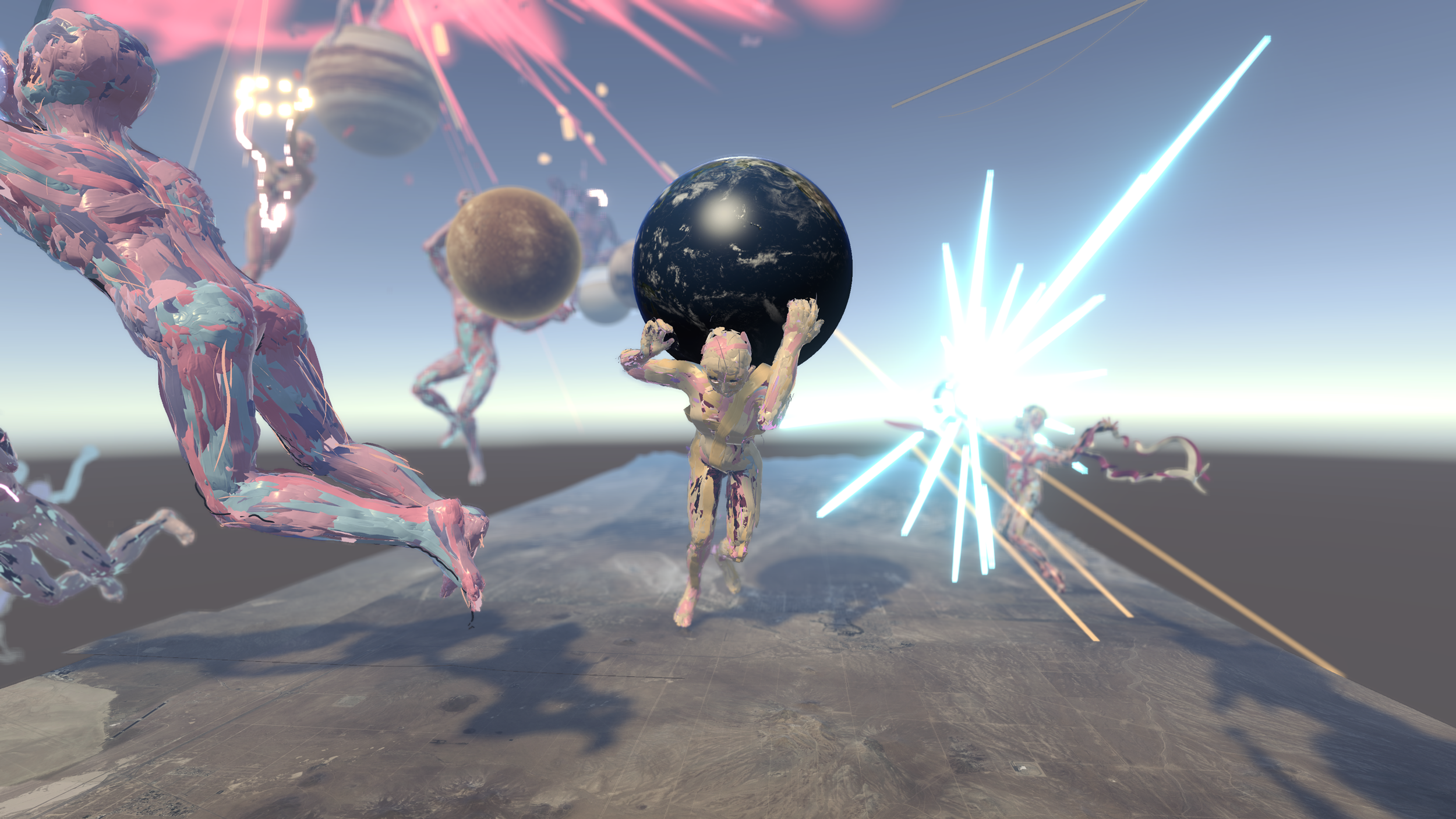

Toward the end of my internship, Dennis let me try on his Oculus Rift to explore a world he had been creating over several years, titled Das Portal. I mounted the headset and found myself in a projected map of California City, a largely abandoned urban development project in Southern California. I began ascending alongside the planets and their namesake Greek gods, which glowed with a Baroque theatricality and dwarfed me in their simulated magnitudes.

After some time of swimming around in the digital aether, I removed the headset and returned to the real world. Reacclimating to my surroundings and to natural light, my body felt lighter, and my sense perception more refined, as if I was seeing again for the first time. I had traveled to heaven and back while barely moving.

On theme with the grandiosity of Das Portal, Dennis often played opera music in the studio. He was particularly fond of Richard Wagner, the 19th-century German composer whose 1849 essay Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft (The Artwork of the Future) proposed the fusion of all artistic mediums into a multisensory total work of art.

This concept feels strikingly relevant to the virtual spectacles produced by Dennis and other artists fascinated with digital technologies. In fact, Dennis has held multiple shows titled Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft, suggesting a Wagnerian vision of all-consuming artwork. Through vivid displays of light, sound, and movement, our devices can approach Wagner’s dream of sublime artworks that enable a total entry into new dimensions of sensation and perception.

II. Rotting Brains, Rotting Bodies

The sensory richness of Dennis’s artwork reveals how digital technologies can activate spectatorship in radical ways. Unfortunately, this potential remains largely unfulfilled in everyday uses of digital devices. In fact, the internet seems to be eroding the body and its sensory perception, as reflected in emerging pop-cultural tropes.

In 2024, Oxford University Press named “brain rot” its word of the year, defined as “the supposed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state, especially viewed as a result of overconsumption of material (now particularly online content) considered to be trivial or unchallenging. Also: something characterized as likely to lead to such deterioration.”[1]

Clarifying the term, Oxford referenced memes like Alexey Gerasimov’s Skibidi Toilet YouTube series, which features 3D-generated animations of toilets with singing heads bursting out of the bowl. The surreal, short-form web series has become popular among Gen Z and Gen Alpha audiences for its addictive, low-brow content.

Skibidi Toilet’s popularity demonstrates that quick, provocative entertainment often succeeds on online platforms. Our digital infrastructure rewards media that bombards the senses with nonsensical visuals and random slogans. The problem sounds frivolous, but online platforms like Physician’s Weekly and Psychology Today have published articles on the adverse health effects of “brain rot.”[2]

A related term, “bed rotting,” refers to “the practice of spending many hours in bed during the day, often with snacks or an electronic device, as a voluntary retreat from activity or stress.”[3] This trend reflects how the endless flow of online information promotes social withdrawal on a large scale. Many individuals can now fulfill their professional and social obligations from bed, creating a screen-based dependency. Architectural historian Beatriz Colomina outlines the consequences:

“The whole universe is concentrated on a small screen with the bed floating in an infinite sea of information. To lie down is not to rest but to move… The bed has become the ultimate prosthetic and a whole new industry is devoted to providing contraptions to facilitate work while lying down—reading, writing, texting, recording, broadcasting, listening, talking, and, of course, eating, drinking, sleeping, or making love—activities that seem to have themselves been turned, of late, into work.”[4]

A new economy and infrastructure have thus emerged to address consumers’ biological and social needs from the bed. Both public and private life are now experienced horizontally, which complicates rest. The bedroom has shifted from a site of downtime to one of constant productivity.

As digital machinery grows ever more integrated with human anatomy, our culture must reckon with the mass alienation generated by our screens. While digital technologies undeniably improve life by enabling global contact and circulating endless knowledge instantaneously, they cannot come at the expense of our mental or physical health.

III. Reawakening sensation

In Glitch Feminism, Legacy Russell finds political potential in glitches, malfunctions in software or equipment resulting in mechanical breakdown. She encourages artists to defy limiting constructions of gender, race, and other identity categories through strategic use of digital technologies to alter human subjectivity:

“We all begin in abstraction: ungendered but biologically sexed bodies that, as we develop, take on a gendered form either via performance or according to the constructs of social projection. To dematerialize—to once more abstract—the body and transcend its limitations, we need to make room for other realities.”[5]

Exposing the arbitrariness of social categories like gender, Russell asserts that glitched beings can undermine hierarchical conceptions of identity by obscuring the boundary between human and non-human:

“Glitch feminism makes room for realizing other realities, wherever one might find oneself. As part of this process, an individual is not only inspired to explore their range online, but also can be moved to quite literally embody the digital as an aesthetic, blurring the divide between body and machine further.”[6]

Russell thus paints the internet’s disembodying effects as an escape from exclusionary social scripts. Online personas, defined by abstraction and multiplicity, offer an unprecedented degree of self-reinvention. This fluidity carries liberatory potential for marginalized individuals, whose bodies are subject to violence. Yet her utopian imagination of glitched, dematerialized bodies stands at odds with present realities of “brain rot” and “bed rotting.” The internet is not liberating the body from repressive confines but rather enforcing new circumstances of its regulation. The challenge remains to restore the full lushness of sensory perception to digital experience.

Aesthetic practice offers a solution. LACMA’s exhibition Digital Witness: Revolutions in Design, Photography, and Film, on view from November 14, 2024, to July 13, 2025, displayed how digital artwork both dissolves flawed conceptions of the body while also heightening its sensory capacities. The show includes various digital artifacts, many outside of the typical disciplinary parameters of the fine arts. One such example is a box TV displaying audiovisual works, known as “demos,” from the Amiga Demoscene, an underground artistic subculture linked to the Commodore Amiga computer and 1990s rave scenes.

Featuring dancing silhouettes of bodies, flashing text, and intense music, the demos encourage action. They share the same dynamic energy as Skibidi Toilet, but the impetus is to move the body. The demos show how digital aesthetics can create immersive experiences of performance and physical connection.

Zach Blas’s Facial Weaponization Suite (2012–2014), also in Digital Witness, mobilizes digital aesthetics for political ends. He critiques mass surveillance by constructing masks that agglomerate biometric facial data on select demographics into abstract, illegible forms. Converting stereotyping datasets into illegible sculptures, Blas circumvents contemporary facial recognition technologies to undermine discriminatory policing tactics, as described in an accompanying video manifesto.

Notably, Facial Weaponization Suite does not erase the body; it is simply obscured. Instantiating a vision of collective identity, Blas exploits technological errors to “provide the possibility of greater mobility for vulnerable bodies who need it.”[7] Multiplicity becomes a shield, allowing oppressed individuals to navigate the world without disciplinary oversight.

Taken together, the Amiga Demoscene and Facial Weaponization Suite show how digital devices can make daily life richer and more liberatory. Digital Witness thus offers powerful evidence that contemporary artists ought to have a greater voice in developing emerging technologies.

Currently, economists and entrepreneurs seem to have all the say in how digital devices are imagined, built, and utilized. Perhaps this is why our culture is so addicted to “rotting”: our devices are engineered to maximize profits rather than to amplify the experience of daily life. Clearly, this formula is not working, as productivity has become a farce performed in the bed. With sensory perception on the decline, it is time to let artists reawaken it.

Special thanks to LACMA’s Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, which supported research for this essay.

[1] “‘Brain Rot’ named Oxford Word of the Year 2024,” Oxford University Press, December 2, 2024.

[2] “Medical Truths Behind Brain Rot,” Physician’s Weekly, December 4, 2024; Krystal Culler, “Brain Rot: Why Brain Health Matters Now More Than Ever,” Psychology Today, December 24, 2024.

[3] “Word of the Day: bed rotting,” dictionary.com, February 14, 2024.

[4] Beatriz Colomina, “The 24/7 Bed: Privacy and Publicity in the Age of Social Media,” in Public Space? Lost and Found, ed. Gediminas Urbonas, Ann Lui, and Lucas Freeman (MIT Press, 2014), 256.

[5] Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (Verso, 2020), 42.

[6] Russell, Glitch Feminism, 43.

[7] Russell, Glitch Feminism, 140.