Mother Tongues: Alva Mooses & Aracelis Girmay

Poem by Aracelis Girmay:

Noche de Lluvia, San Salvador

Rain who nails the earth,

whose infinite legs

nail the earth, whose silver faces

touch my faces, I marry you. & open

all the windows of my house to hear

your million feral versions

of si si

si

si

sí

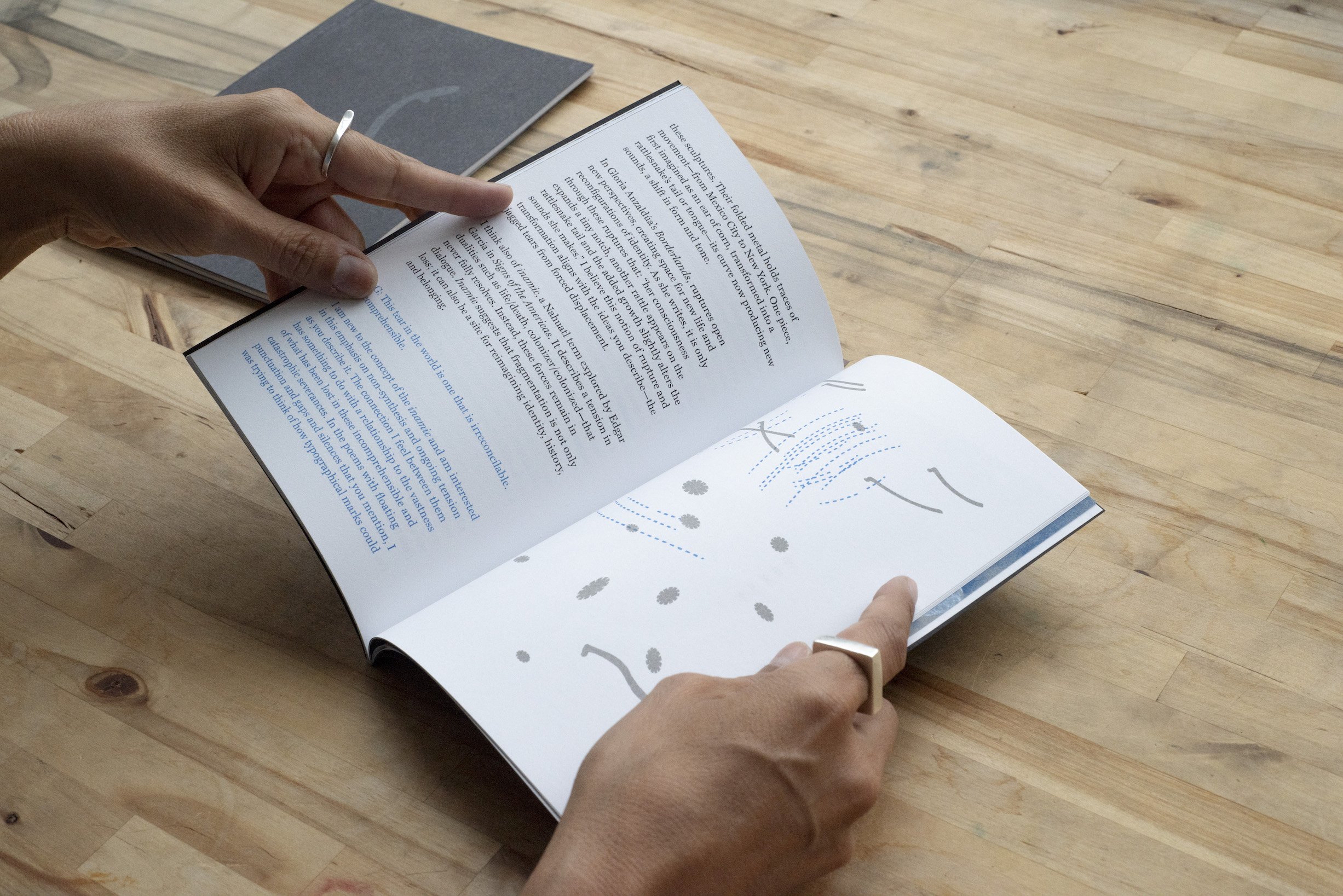

Earlier this year, artist Alva Mooses and poet Aracelis Girmay participated in Mother Tongues, an exhibition at the Brooklyn Central Library. Installed in the Library’s Grand Lobby, their works engaged with translation, ancestral memory, and the shifting boundaries between visual and verbal expression. Their dialogue was recently published by Hverdag Books in Norway. What follows is an excerpt from that conversation—an exchange that considers how the materiality of poetry and visual art speak to one another.

Cora Fisher: Aracelis and Alva, I’m interested in what poetry can teach us about the materiality of visual art and the materiality of language in the exchange between your works. How can poetry help us see the physical materials in artworks as speaking? Reciprocally, how might visual art reframe our understanding of the aural/oral transmission of language? And what might these formal processes expressed in physical materials, written word, image, and sound have to do with how we remember and how we imagine?

Alva Mooses: I work with metal and clay because I’m drawn to the ways these materials hold and release impressions, allowing for transformation. The clay sculptures I make are often extruded or slip-cast from globe models, reimagining the earth using its own elemental substance. Mapping becomes both a language and a system that can locate and disorient. These warped globes reject the colonial project of Western cartography and offer alternate worlds, languages, and systems of measurement, giving the material voice and agency.

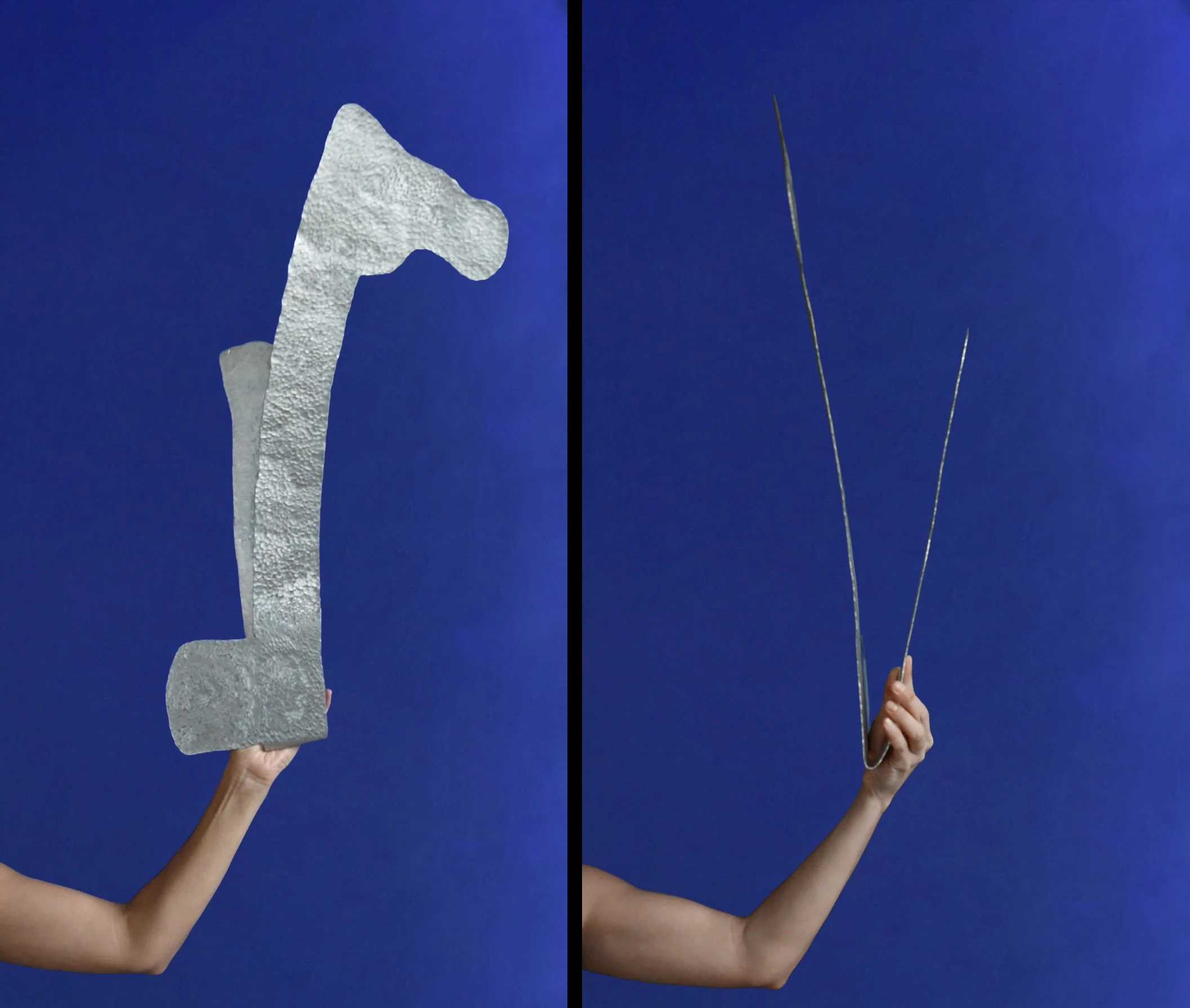

This gesture extends into metal: cutouts translated from clay into aluminum, jagged with intention, suspended, held, and sometimes sounded. They resemble measuring tools or fragments of sign-systems—world-devices, uncalibrated. When printed on paper, they multiply. And printmaking, like poetry, resists immediacy. It records slowness, repetition, and error.

When reading your poems, Aracelis, I think of how the body, too, holds memory—how language flows from it, layered and unfinished. Your work reminds me that loss, love, and grief are currents we navigate, constantly in motion, shaping and reshaping us.

Aracelis Girmay: To read your word “jagged” now, in the context of your making, helps me articulate that part of what I respond to here has to do with the trace of something torn, transferred, moved. Processes may be gentle, natural, and gradual, but the way I am feeling them now is more brutal and forced than any of this. I am thinking of Dionne Brand’s A Map to the Door of No Return.

Your metal sculptures hang on a line. A line of languages? Processes? Histories. And I wonder about the material accumulation of place(s) in the metal. In my book the black maria I am thinking about Eritrean history but also generally about people leaving Africa and crossing the Mediterranean into southern Europe, as well as the various systems and lineages of violences waged against them as they seek asylum. I wanted to write a work that signaled it was a shard, a ruin, a coil of hair.

AM: Suspending the metal on a line is like composing a line of language, or a phrase of sound. I think of hand-setting type, where the spaces between letters, the pauses, shape the poetics as much as the forms themselves. I see a similar care in how you shape your poems, how punctuation and spacing hold meaning. The folds in the metal hold traces of movement from Mexico City to New York and at each place, I’ve collaborated with musicians to sonically activate the sculptures. One piece, first imagined as an ear of corn, transformed into a rattlesnake’s tail or tongue—its curve now producing new sounds, a shift in form and tone.

In Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands, ruptures open new perspectives, creating space for new life and reconfigurations of identity. As she writes, it is only through these ruptures that “her consciousness expands a tiny notch, another rattle appears on the rattlesnake tail and the added growth slightly alters the sounds she makes.” I believe this notion of rupture and transformation aligns with the ideas you describe—the jagged tears from forced displacement.

I also think of inamic, a Nahuatl term explored by Edgar Garcia in Signs of the Americas. It describes a tension in dualities such as life/death or colonizer/colonized that never fully resolves. Instead, these forces remain in dialogue. Inamic suggests that fragmentation is not only loss; it can also be a site for reimagining identity, history, and belonging.

AG: These tears are irreconcilable. Incomprehensible.

I am new to the concept of the inamic and am interested in this emphasis on non-synthesis and ongoing tension as you describe it. I am interested in the way you describe the printed record of the sculptures and their more ephemeral, live acoustic presence. The voice reading the poem and the touch pulling sound from the sculpture make me wonder if the shapes (of the metal and the lines) themselves can also signal that they are on their way to losing themselves, as in your globes from culebra, truena, tormenta. This makes me think of transfers, translations, echoes, traces as ephemeral but also (sometimes opaque) remnants of sustained information.

AM: I love the idea you mention of pulling sound out of the metal pieces—by printing and recording their impressions on paper, they continue to live on in another form, resisting erasure.

My mother’s family is from Coahuila, Mexico, a desert region near the Texas border. I spent summers there as a child, visiting adobe houses that endured for generations before returning to the earth they were made from. This region is under increasing threat from drought and industrialization. The US-Mexico border is vast and holds many paradoxes. The SpaceX launch site, on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, prioritizes space colonization over human rights, as people are denied refuge, detained, separated from their loved ones, and then they are given the same metallic blankets designed for space exploration.

AG: The prioritization of the total freedoms of the billionaires over everyone and everything else on this earth is absurd. And then there is the powerful thought of your family’s adobe house, and the adobe houses made of the earth that then eventually go back into the land. I think of home-loss and displacement so much, but mostly in relation to displacements fueled by empire or tribalism of all kinds, human wars, massacres, industries. But then you write: “the adobe houses that endure for generations before returning to the earth they were made from.” The initial gasp I feel to recognize what you say about the possibilities of decomposition, loss, and change helps me to realize that my position, focused on the state’s violations of life, has perhaps warped my sense of loss generally speaking. This conversation and your work help me to articulate this struggle. I have to hold both armor and dreaming at once. To think about these relationships to change, to life, to the births and deaths of form in your work is very meaningful to me—tremendous, beautiful, and difficult.

AM: The way you name the “struggle to hold both armor and dreaming at once” opens up so much. I like to think my work leans into this tension—armor plus dream—in the moments the aluminum sculptures are sounded, held, and transformed.

I think of how a mother’s intonations are one’s first perception of language. My relationship to a hybrid English and Spanish is shaped by histories of migration and colonization, generations of people reshaping language amidst new and shifting realities. We also pass down information that transcends written and oral languages. The lineages of healing practices, doulas, and sobadas passed down through the Mexican women in my family are intimate acts of protection and resilience. In a time when maternal care, reproductive rights, and bodily autonomy are increasingly under threat, these embodied traditions are all the more urgent.

I’m reminded of M. NourbeSe Philip’s notion of English as "a foreign anguish" in her piece "Discourse on the Logic of Language" from She Tries Her Tongue. She powerfully points to the violence embedded in language itself. Yet through the persistence to hold or reshape one’s languages, rhythms, and intonations—expressed in poetry, music, dreams, art, storytelling—one can potentially forge a path toward something new, revealing portals that urge us forward.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Mother Tongues was on view at the Brooklyn Public Library from April 7 to June 7, 2025.