Lance Weiler on Memory, Mystery, and Algorithmic Grief

Through the RLWindow of RYAN LEE Gallery, Lance Weiler’s Where There’s Smoke invites passersby to pause and enter a deceptively simple interactive system. The installation asks viewers to text a prompt (“SMOKE”) that triggers a cascade of responses. When four people text, the large screen shifts into a living mosaic of incoming messages. Participants are prompted to answer what object they would save if their home were on fire, and the system asks “why” five more times. These entries form part of a digital ledger, allowing the project to maintain an ever-compounding existence that meditates on permanence and loss.

Interspersed with these public interactions are Weiler’s live performances. Using layered slides, artifacts, and a camera that survived a childhood house fire, he moves through Miro collages and toggles visual and sonic elements in real time. Rather than a fixed narrative, Where There’s Smoke is a constantly shifting portrait of memory, grief, and intergenerational echoes. As its technology intentionally recedes behind emotional resonance, what emerges is a piece that evolves with each encounter.

Xuezhu Jenny Wang: Where There’s Smoke asks the viewer what they’d save in case of a house fire. What would your answer be to this question?

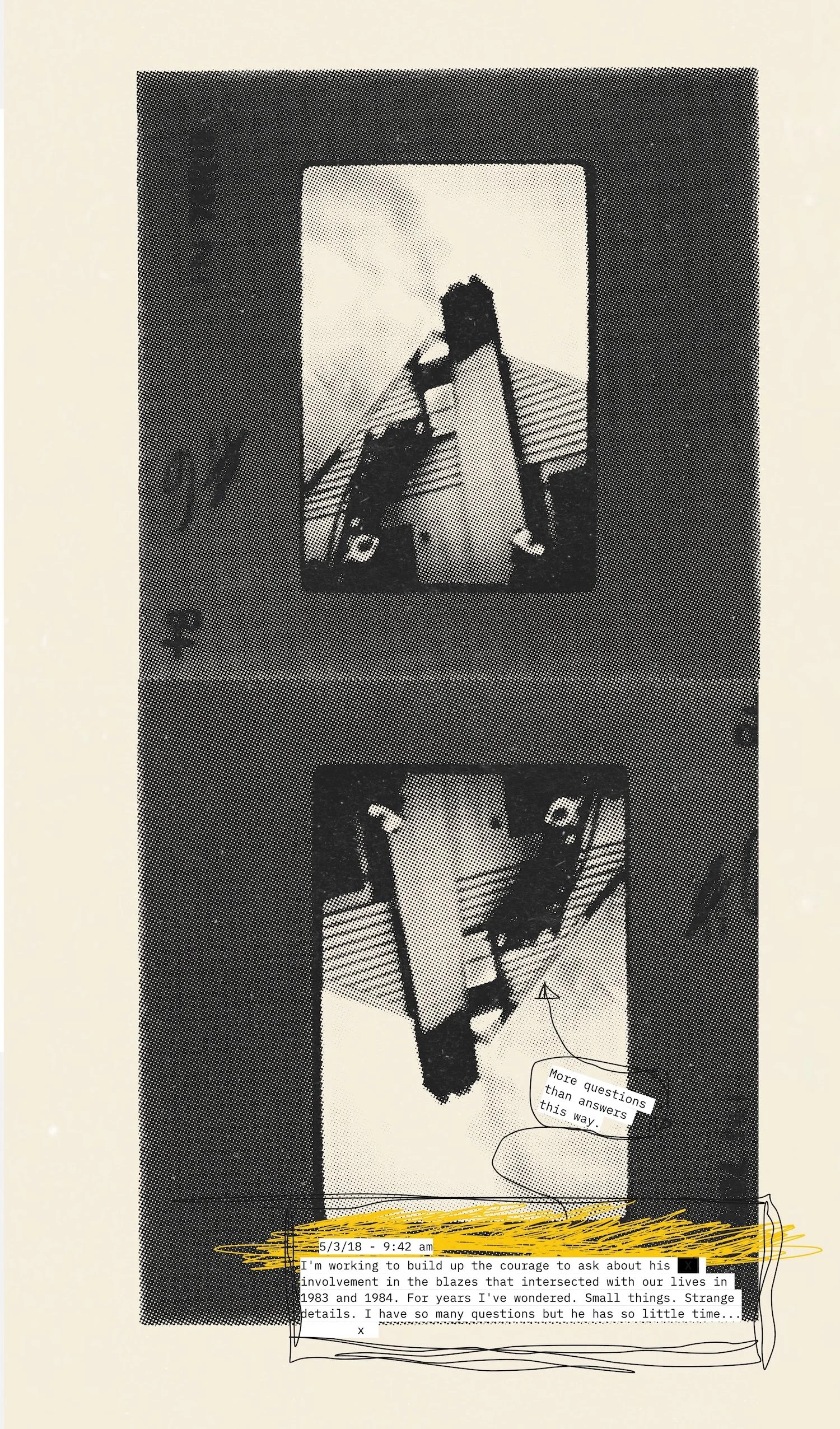

LW: This camera—it actually went through a fire. The piece is rooted in growing up in a firefighting household. My dad was a volunteer firefighter and amateur fire-scene photographer. We experienced two devastating fires: first a van fire on vacation, then, eleven months later, our house burned down. For years, I wondered if my father had anything to do with them. When he was dying of stage-four colon cancer, he asked me to interview him and said I could ask anything. I recorded about 15 hours, which became the backbone of the work. I could have made a film or TV show, but I wanted something malleable—like memory—an immersive piece.

Jubilee Park: The installation feels guided, but not predetermined. Are you responding to a preset narrative?

LW: There is a narrative framework, but it’s in constant dialogue with the audience. The project has evolved through multiple iterations: a burned-out storefront installation in 2019; hundreds of virtual shows during the pandemic where I collaged live in Miro; a 3,000-square-foot version with sensor-embedded flashlights that generated a score; and now the RLWindow iteration at RYAN LEE Gallery with live performance. Each format shifts how the narrative surfaces. The fire-scarred camera appears each time, but the story reveals itself differently depending on what the audience contributes. The work is structured enough to hold its shape but porous enough to absorb new meaning.

JP: Does technology help you manage the complexity of that participation?

LW: It does, but only if I let it recede. The work began with a mystery: whether my dad was an arsonist. It took me 17 years to face it, and his illness forced the conversation. The technology—IoT triggers, browser-based interaction, microcontrollers—supports a narrative arc that mirrors grief: initial control giving way to ambiguity, contradiction, and vulnerability. It’s generative but still deeply narrative, which is rare.

XJW: After working with these personal and family histories, it almost seems like it doesn’t matter whether or not he was the arsonist.

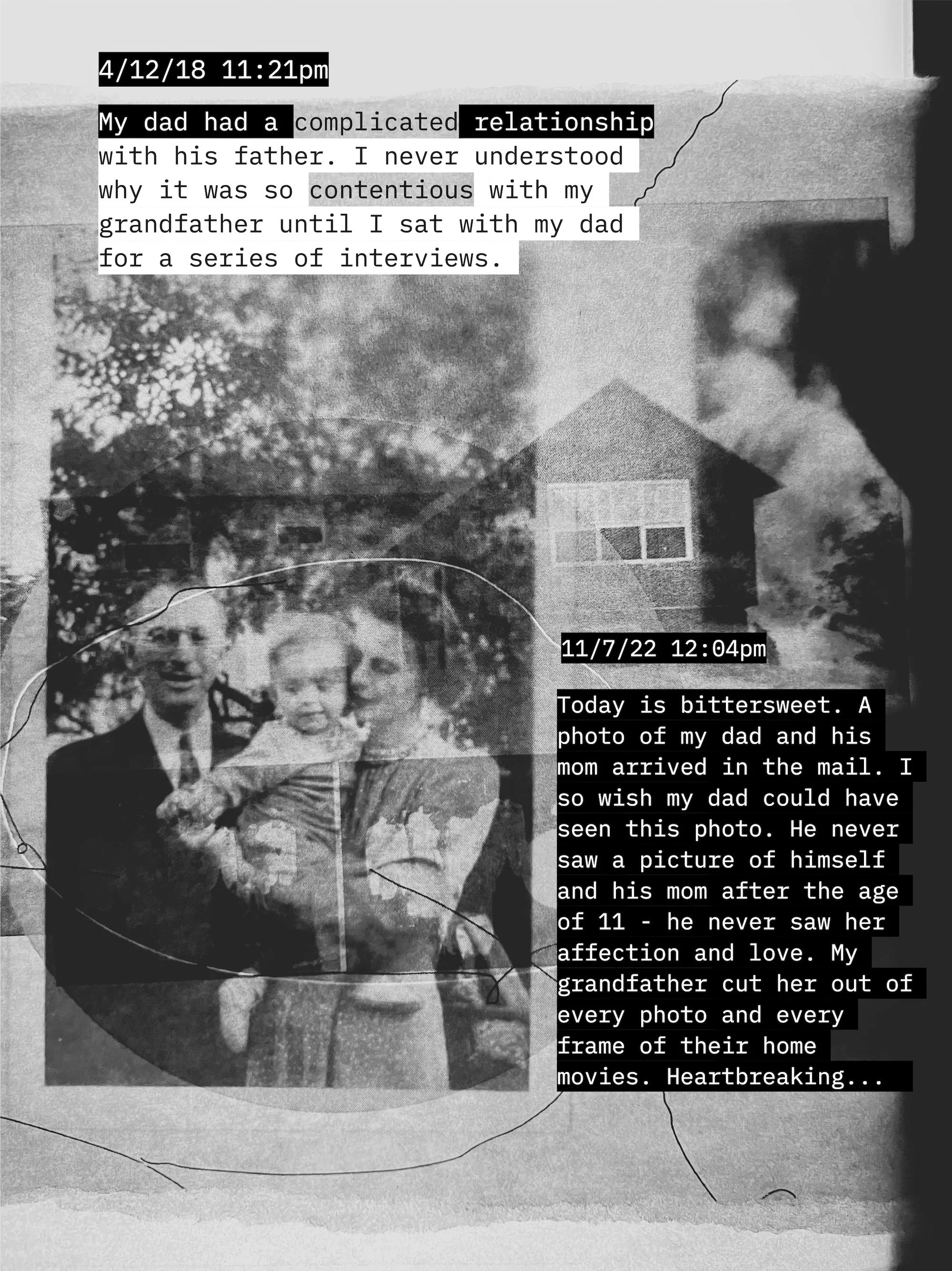

LW: Exactly. I ended up with more questions than answers, like memory itself. In the final interview about the house fire, new details surfaced that reframed our entire family history. When my father was 11, his family moved houses, and when the truck arrived, his mother was gone—he never saw her again; years later, he learned his father had paid her to stay away and erased her from every home movie and photograph. When I was 11, my dad accidentally left my mom at a rest stop in the middle of the night while on a family vacation, then he left me alone for more than 24 hours in a motel just in case she called. And when my son turned 11, he went to see the Tribeca installation of Where There's Smoke with his grandmother. These repetitions and narrative rhymes became more meaningful than the question of arson. The piece is less about solving a mystery and more about tracing how unspoken stories echo through a family, shaping what we inherit and what we pass on.

XJW: A TV series would make that storyline explicit. But in an interactive work, the plot can get lost. Why accept that ambiguity?

LW: Because memory is ambiguous. When people text, they can either hear an audio fragment or contribute words that become part of the ledger. Over time, I’ve released the need for neat clarity. What once felt urgent stopped being the point. After my father passed, I found 60,000 35mm slides. Many are beautiful, haunting images, and they introduced even more uncertainty. The work embraces the decay and distortion inherent in remembering. Narrative appears, dissolves, and reappears. That feels truer to how we actually process lived experience.

XJW: Could you talk about the Digital Storytelling Lab and how it informs your practice?

LW: I started the Columbia DSL over a decade ago to explore new forms and functions of storytelling. The forms involve emerging technologies—IoT, AI, and AR. The functions involve storytelling as a tool for learning, healing, mobilization, policy change, entertainment, and the arts. My own practice moved from writing and directing films into building participatory environments, so the lab is an extension of that curiosity about how stories behave when multiple people shape them.

XJW: At the intersection of technology and art, is there still a return to the human?

LW: Absolutely. I want the tech to feel invisible even when it’s sophisticated. Those flashlights in earlier iterations “just worked”—people didn’t realize they were part of an instrumented system. I’m influenced by experimental film and the aesthetic of digital decay: GIF layers that erode, glitch, artifact. These imperfections open up space for memory and emotional resonance. I also intentionally subvert productivity tools—like turning Miro into a collaborative storytelling stage—to reclaim digital space as a site of performance rather than optimization.

JP: How does glitch aesthetics relate to your work?

LW: I love glitch art: imperfection, error, and the way decay opens memory. My brothers and I remember events differently; glitch aesthetics mirror that malleability. It resists polish and pushes back against systems that control our media and data. Glitch can be empowering while recontextualizing a long-lived personal story in a documentary-adjacent way.

XJW: Do you see technology as carrying an inherent emotional charge, like painting or sculpture?

LW: Technology is seductive, but it can dictate experience if you let it. I’m more interested in subverting its intended use. This installation runs 24/7 from an algorithm we wrote, accumulating hours of shifting material so the screens develop a kind of generative, memory-like behavior. I’ve also been experimenting with blockchain as an emotional ledger, trying to understand what “permanence” might mean in a family history marked by disappearance. Certain moments in the piece create small on-chain inscriptions, traces of an encounter that can be revisited or felt again. During the pandemic, one virtual attendee drove nine hours afterward to reconcile with an estranged, dying father. That kind of response goes far beyond interface design; whether it’s algorithms or blockchain, the technology is just scaffolding. It’s the human layer that carries the charge.

JP: Where does the project end?

LW: It doesn’t, really. It’s generative and open-ended. Eventually I’d like to create a culminating installation that integrates everything: the four-channel system, my father’s photographs, the code and dataset that drive the generative components. I’m also interested in a living art book—part process document, part grief ritual, part philosophical study of how technology can resist its default logics. With so much unregulated AI, there’s room for emotionally resonant work that proposes alternative uses for tech. So: to be continued.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Lance Weiler: Where There’s Smoke is on view at RYAN LEE’s RLWindow from September 4 to December 20, 2025.