What Comes After the Real

We live in the glare of simulation. Our everyday is full of tests that ask us to verify what we know—Was that apology sincere? Was the invitation genuine? Is this video AI or not? But the question is shifting. It is not What is real?, but What is reality meant to feel like? What are the rules of that feeling? What are the stakes of getting it wrong?

Some of us love a stunt. We stage the conditions for coincidence, arranging people and moments to see what they hold. These small experiments test the boundary between reality and performance. MIRA Festival is set within this atmosphere of performance and belief. It gathers artists, students, and audiences who may no longer expect revelation but still want to feel it. The festival’s head programmer, Pau Cristòful, described the festival as “creating conditions for emergence.” MIRA functions through a shared act of holding something together, and the audience understands the construction as much as the makers who have manufactured it. In wrestling, this is called kayfabe. The reality of the event is sustained because people choose to believe in it together, and the performance becomes real through collective attention. At MIRA, the immersive installations work the same way. There was far more to see than could be fully processed in a single weekend, yet the following works made this construct most apparent.

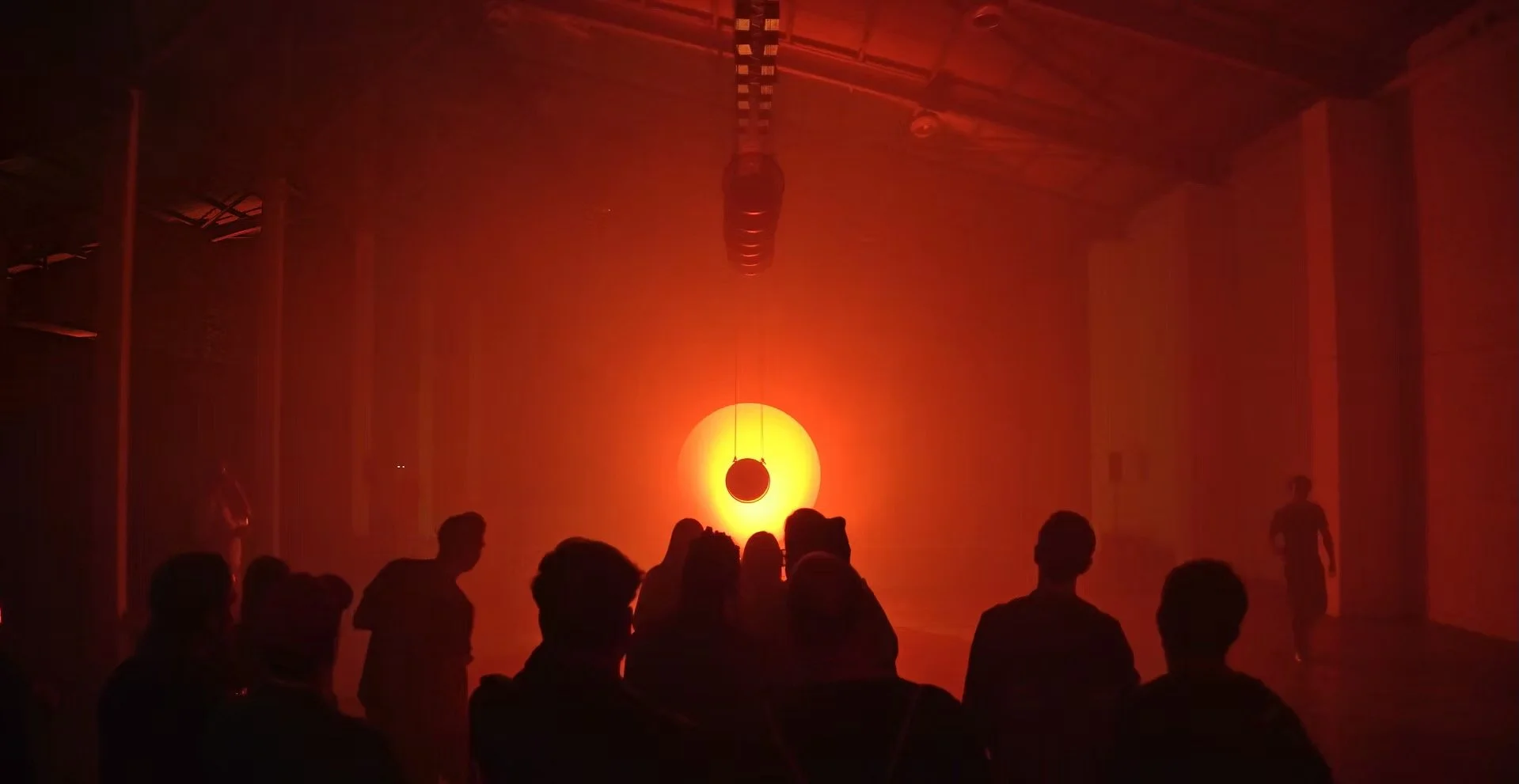

Sven Sauer: Solis

Solis is a work by Berlin-based Sven Sauer, who is interested in how social atmospheres form in cities. The sculpture operates as an artificial sun suspended in a dim environment. It recalls a natural force that has been rebuilt by human hands; The sun is both present and absent. Its effect depends on a willingness to accept daylight inside a dark factory at night, and it works only when the viewer lingers long enough for the body to respond. This is the logic of the hyperreal: the image feels real because we register it physically before we analyze it.

Lolo & Sosaku: Perros

Lolo & Sosaku began working together in early-2000s Barcelona, and their practice draws from industrial music, mechanical engineering, and kinetic sculpture. The site-specific installation Perros carries this forward, with a group of metal structures linked through chains and motors. Perros’s accompanying performance relies on being physically present within the installation. A crowd formed around the work, so the machinery could only be seen clearly from inside, and the sound arrived before the visual. During the performance, tools and parts were adjusted in real time, sending literal sparks flying. The scene could not be understood at a distance—it required entering the center of the gathering rather than observing it from outside. In this way, the work’s coordinated quality emerged through both the forms and the crowd that condensed around them.

IED Barcelona and La Salle-URL: Torbellino and Rabia

The interactive works throughout the festival made the viewer responsible for the experience. From the students at La Salle-URL, RABIA took the form of a suspended punching bag wired to a projection system, each hit sending different visuals across the screen in front of it. From IED, Torbellino used fabric, light, and movement to create a sensory environment. Long sheets of material formed soft tunnels that people could move through, and the projected light shifted as bodies passed. The installation suggested an aliveness in the fabric, as if it responded to those who entered.

In the end, it was the music that articulated the environment most clearly. Far from a backdrop to these installations, it set the terms. In that duration, the question of realness was no longer the point. This is what comes after the real: not truth, but the temporary world that a group agrees to live in together.