Illuminating Queerness through Haze and Shadow

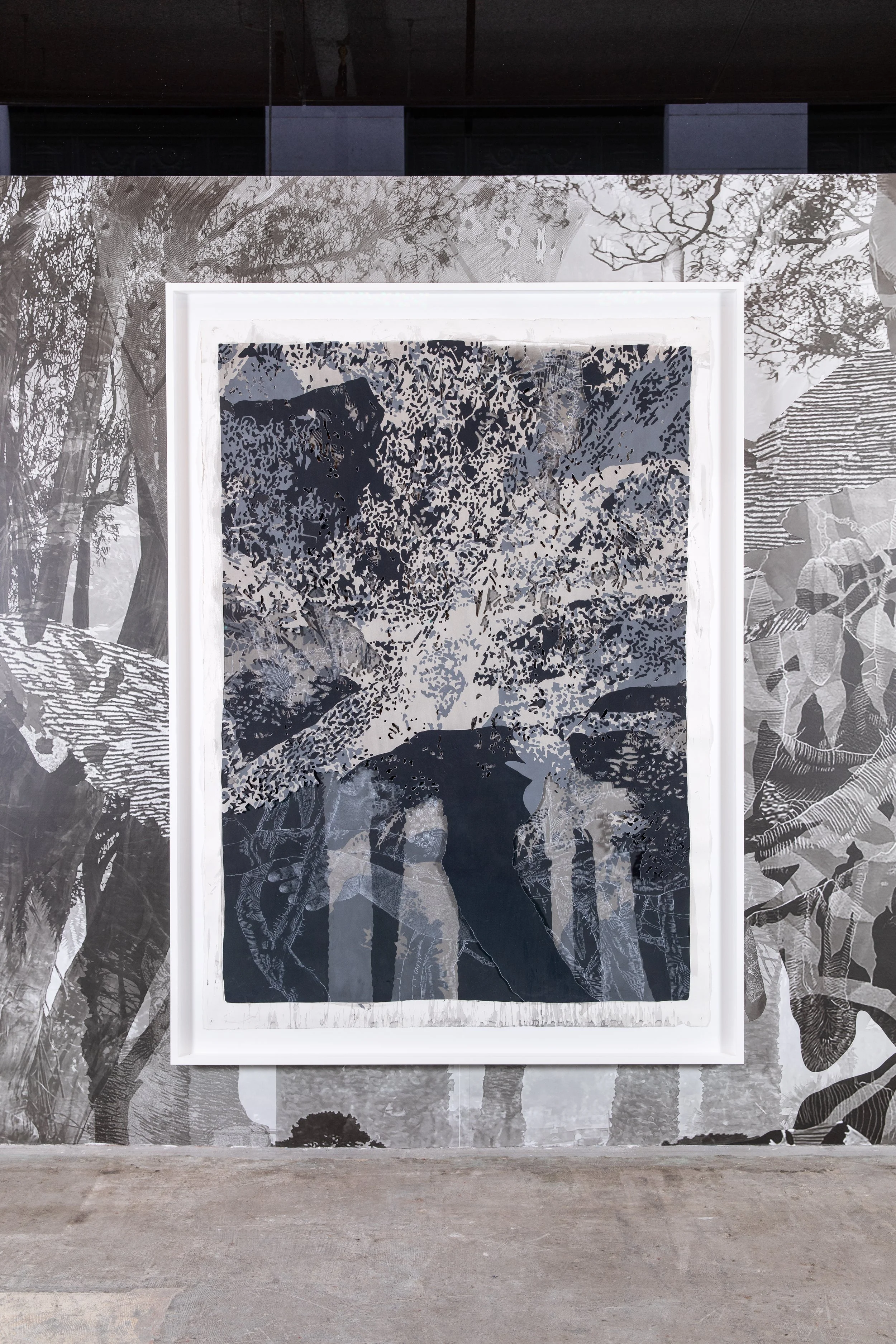

That unmoored, disoriented sensation which washes over a viewer when peering closely into andifeelyourbodyclose,ifeelikeineedsomemore (2025) is an invitation to keep going, to look even deeper. The work, included in David Antonio Cruz’s stay, take your time, my love, on view on ICA San Francisco’s first floor, starts with a stain and layers obstructions of ink, cutouts, and flashe to reveal the subjects beneath. “There’s a moment where the body is rendered and yet it becomes abstracted, it becomes a different space,” Cruz intones during a video call from his Bronx studio. Drawings in progress dot the background as he fills the foreground with punctuating, excited gestures, moving and removing his glasses when a particular idea captures him. At a certain point in his practice, the portraits became landscapes: “It becomes space. It is the home. The body is the space; the space is the body.”

A twenty-minute walk south of ICA SF, the group show To Be Seen at Jonathan Carver Moore, which includes two works by Khari Johnson-Ricks, similarly jars and disrupts viewership. The figures of Canopy, cradle, breeze/ keep you near me (2025), painted in watercolors over suminagashi marbled paper, stretch further and further away from the eye, as the scene in which they’re placed—perhaps a bed, perhaps just a canopy of haze—pulls the gaze deeper in. On the opposite wall hangs Onsen uu (2025), similarly saturated in watercolor and ink but taking the viewer to a bird’s eye perspective of a bath. “These are not surveilled spaces in a traditional sense,” Johnson-Ricks explains over a call from Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, where he is completing a residency. He continues that a surveillant quality exists in the “ubiquitous gaze” of being in a spa or sauna with another. “The overhead perspective felt very much like a gesture towards the circumstance of those spaces . . . your sight and the circumstance are mitigated by steam or mitigated by the perspective of relaxation and pampering.”

Both artists’ practices of portraiture utilise recognizable composition norms. A family is gathered, posed on and around stately furniture or figures captured in a moment of repose, which is then confused: “The painting itself looks like their bodies are rumbling out, so it becomes top-heavy,” Cruz describes. The subjects lunge at the viewer. “Physically, it’s impossible. You're sliding under the couch, you become the floor.” The centered piece, stay,takeyourtime,mylove (2025), made for the ICA SF show, is made up of two panels which don't quite meet. “One folds and slides so that it becomes a door in order for you to be able to step into the painting, it allows for that possibility.” Space remains a recurrent focus for each artist, the space for possibility.

In Johnson-Ricks’s case, it is the ever-shrinking space before contact, a sensuality which rejects the step into corporeal erotics. “I try not to make an image that would front-load sexuality on the images just because I understand how Black men are experienced, and how Black men experience spaces where they are publicly nude,” Johnson-Ricks details. “They become hypervisible, hypersexualized, become the subject of a kind of critique that most other bodies don't have on them.” But it is not enough to simply upend some expectations; instead, each remains fixed on the in-between, the gap: disrupting the hierarchy of positive-negative space. “I do identify with this haze or this kind of misreading of an environment, especially one where you might go to be relaxed, to bathe, to experience care and pampering.” The sauna transfigures into a hyper awareness of sight and desire, the being seen and seeing, the anxiety of what gaze one is producing in this environment and inadvertently inviting. Even the dark corners become deeply significant: “I think of the spaces between the bodies as that space,” Cruz says. “It becomes runny, and yet it's still a physical space. That is the queerness in it that I think of when producing the work.”

Two distinct practices are linked by their sight through shadow or mist—the unseen, obfuscating space—as sites of possibility. Both are invitations to transformative intimacy in their own respects. The projects meet in their disruption of viewing with skewed perspective, at times obstructing the body more literally, in the case of Cruz’s installation of a 32-foot bench swathed in custom print upholstery running the length of the exhibit. His glitched repetitions of subjects’ body parts in uncanny, saturated impositions and Johnson-Ricks’s gauzy papers invoking the dreamlike state of bathhouse haze and heat conjure thoughts of cruising. The disorientation and opacity of their works invite viewers into an intimate act: to recognize the palpable need to shed the assumed and unexamined sightlines on queer bodies that viewers may already carry. Thus, the gap between the viewing body and the work closes by ever-increasing increments.

Both artists speak with some reverence for that space between— just before touch—staining the negative space with even more potential through elements like shadow and haze. Amid the cognitive dissonance of queerness being ever more visible and represented, yet performed without care or intentionality, Johnson-Ricks’s and Cruz’s works invite a consideration for queer visibility which affords legibility to those willing to step into these spaces of possibility. As queer folks appear both hyper-present yet even more at risk in media, politics, and our collective consciousness, these artists’ methods of effecting viewership via opacity and obstruction each offer alternative avenues for engaging with what it means to be seen. Queerness under Johnson-Ricks and Cruz’s depictions is recognizable until it is not. When asked about their own sentiments towards opacity, they each retort with some version of, “To whom?” Assimilation is an effort to curate one’s otherness in a fashion that the majority can digest to consume, but therein erase. To remain this somewhat illegible, opaque subject is to allow the more generative gaze in. Thus, both artists interrupt accepted sentiments around representation alone as enough for marginalized identities. Unlike the gloss and rainbow of presupposed, corporatized queer iconography, their work readily returns the volley onto the viewer’s gaze. “To whom?” they both assert, earnestly inquiring who is on the other side.

To Be Seen is on view at Johnathan Carver Moore Gallery from June 6 through August 16, 2025.

David Antonio Cruz: stay, take your time, my love is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art San Francisco from May 16 through December 7, 2025.