Gisela McDaniel on Painting as a Communal Process

Over the last nine years, artist Gisela McDaniel’s work has been driven by a core question: how can we hold each other’s stories? Her interview-based practice is rooted in collaboration, informed by her connection to her CHamoru ancestry. Tracing her maternal lineage to the island of Guam, or Guåhan, McDaniel attributes her cultural knowledge to her family—particularly her mother, a sociologist. Painting is her unique way of preserving history, the visual equivalent of a shared oral tradition, “like when your aunties are gossiping,” she tells me, but “never negatively.”

“Respect and listening to others is a big part of CHamoru culture, so my practice grew out of the values my grandparents instilled in me,” McDaniel says. She often asks her subjects, usually women or non-binary people of color, about their hopes, fears, and memories, then integrates the sounds into multimedia pieces. “My work also grew from my own experiences with violence and realizing that a lot of us were carrying similar stories around. I needed to release it from my own body.”

When we meet for our interview, McDaniel is celebrating a solo show at Superposition Gallery, If the land continues to be eaten by this scary thing, our land will definitely become divided in two. Its title references an ancient CHamoru legend about how Guåhan got its distinct crescent shape: one day, a giant fish threatened to swallow the island, nearly splitting it in two. While men failed to kill the creature, a group of women saved Guåhan by using their hair to weave a magic net, luring it to its death with a siren song.

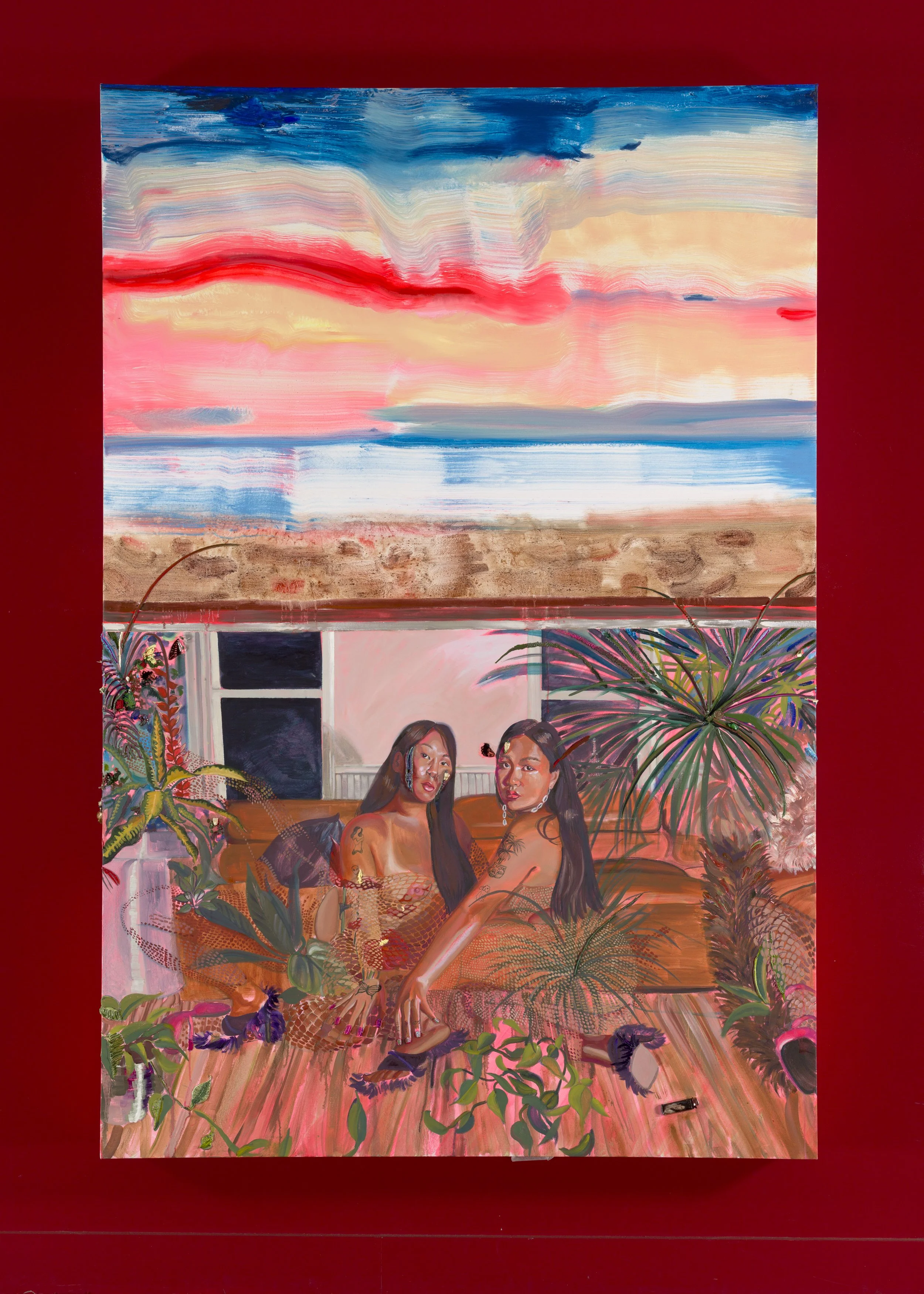

Fishnets are a recurring motif throughout McDaniel’s work, contrasting fleshy femininity against the austerity of a barbed-wire military base—an allusion to the US colonization of Guåhan. Masks inspired by Pasifika culture function similarly as a protective barrier, creating a sense of distance between subject and viewer. Alongside letting her sitters choose their poses and outfits, McDaniel asks them to bring their favorite keepsake, or what she calls a “consensual artifact,” and affixes these to the paintings: imagine anything from an Amy Winehouse lighter to literal human teeth, as seen in the piece Not enough patience in this world (2025).

“I think control is important. Ultimately, I want people to like their portraits because portraiture is history. Being an islander and looking at Gaugin’s work [of Polynesia], for example, none of them look happy. And you don’t even know who they are,” she says. “I want to celebrate the lives of the women and femmes around me.”

In McDaniel’s paintings, the land is its own subject, influenced by Indigenous beliefs about the earth’s sanctity. On Guåhan, locals revere the jungle as sacred, specifically on the northernmost point, Ritidian (Litekyan). Highlighting the pitfalls of the island’s US-controlled nuclear testing sites, the artist’s newer pieces showcase a selection of artificial neon colors. She’s also incorporated melted plastic to call attention to climate change and how rising sea levels pose larger risks to Pacific Island nations. During a recent trip back, McDaniel even managed to sneak some soil in her suitcase, which she’s been spreading onto different works.

“Since a third of the island is a military base, they’re the biggest contributors to pollution. There aren’t any birds on Guåhan either, because the US introduced an invasive brown snake,” she says. “Sexual violence statistics are really high because of the military, too. Obviously I have the privilege, being from the United States, to say ‘fuck the military.’ But it’s a lot more complicated there. There are varying opinions about independence.”

McDaniel’s first museum solo show will open in August at the Ogunquit Museum of American Art, adorned with ocean wallpaper to match the beautiful view. The exhibit spans around 25 paintings she made while living in Los Angeles, New York, and Detroit, from depictions of friends, relatives, and activists to her self-portraits. It’s the first time these pieces will all hang in one place, she points out, the culmination of half a decade’s worth of work. Of course, her community is ever-expanding, and she encourages anyone interested to respond to her open calls for sitters on social media.

Like other diasporic artists, McDaniel is always navigating the friction between longing and belonging, bearing the brunt of being a spokesperson while still learning about her homeland. “As someone who is mixed, it’s hard to feel worthy of representing your whole culture, but I'm trying to do a good job,” she says. “At the end of the day, being CHamoru is more than just my DNA. It’s how my mother raised me, it’s who I am.”

Gisela McDaniel: ININA is on view at the Ogunquit Museum of American Art from August 1 through November 16, 2025.