Hannah Wilke’s Enduring Gestures

The term “gestural” often veers toward hollow art-speak, reduced to shorthand for painterly bravado or expressive flourish, particularly within the patriarchal canon of abstract expressionism. Hannah Wilke, however, lends specificity to the word. Through her insistently embodied approach, the New York-born artist (1940–1993) collapsed process and product, imbuing each work with tactile resonance. Her sculptures, paintings, and sketches are charged with sensual immediacy, bearing the residue of material negotiation. Abstract Bodies, a modest one-room exhibition at Petzel in Chelsea, foregrounds two recurrent gestures in Wilke’s late practice: the fold and the stroke.

I. Fold

“Fold” connotes both an action and an object. Wilke first mobilized this simple gesture in the 1960s, while seeking to establish her position within the male-dominated arena of minimalism through “a formal imagery that is specifically female,” as noted in the exhibition text. These organic, vulvic forms became a sort of iterative signature developed throughout her career.

At the center of the space, Primary Life (1983–1992) consists of nine ceramic folds in red, yellow, and blue, evenly spaced atop a low gridded platform. The checkerboard of bright primary hues lends a playful, even nostalgic, quality, with the folds reminiscent of oversized board game pieces. Nearby, Untitled (1987–1992) offers a darker counterpoint with thirty-eight all-black folds strewn more loosely across a monochrome surface.

Through the simple transformation of a flat plane into a three-dimensional object, Wilke lends immediacy to these forms, retaining indexical traces of her hand. In both installations, the organic curvature and tactile irregularity of the folds undermine the rigid austerity of the grid, transforming this minimalist framework into a site of sensual potential. Whereas Wilke’s earlier palm-sized folds in Play-Doh, latex, and other malleable materials more apparently conjure vaginal associations, these scaled-up sculptures are more ambiguous, albeit no less corporeal. In dialogue with the surrounding watercolor portraits, the folds even seem face-like.

II. Stroke

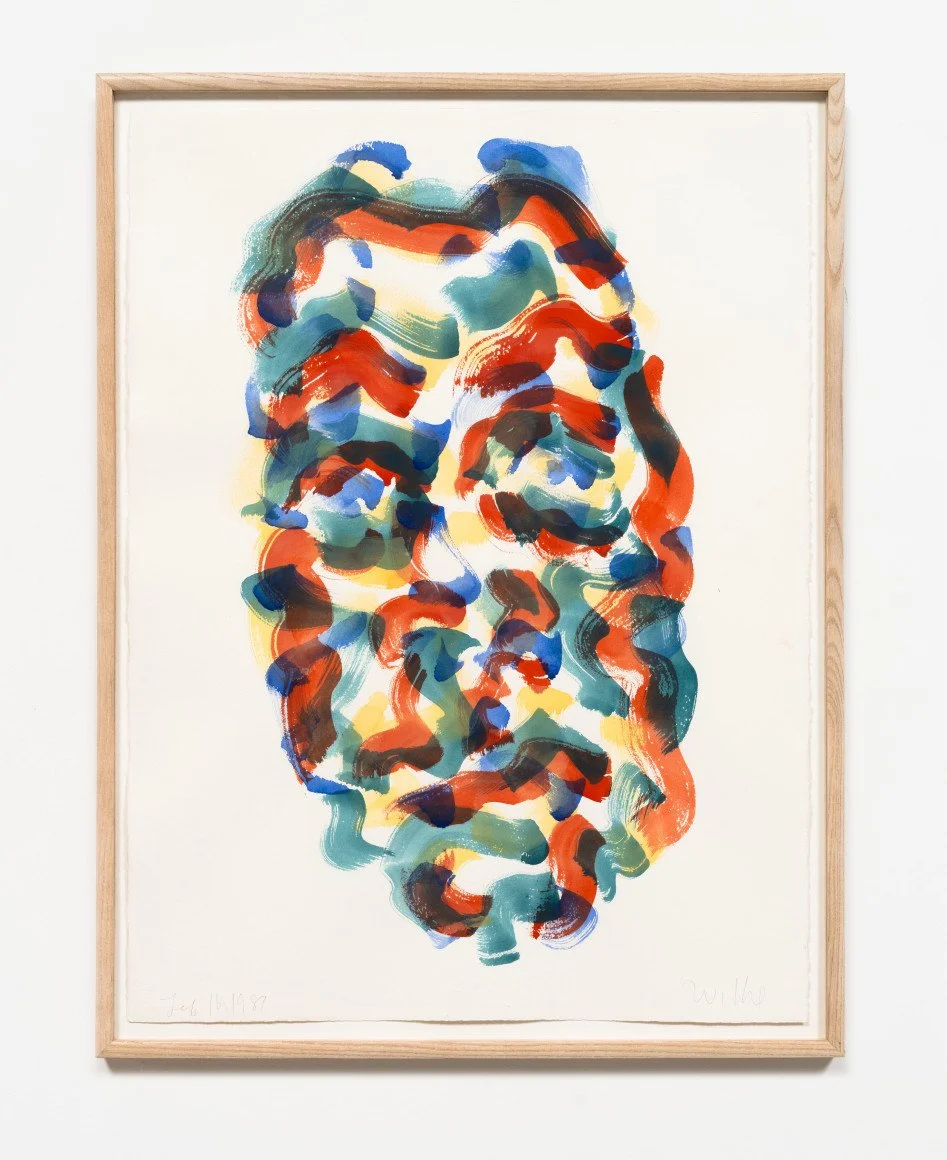

The brushstroke—or the “stroke” itself—likewise functions as both verb and noun. Wilke’s B.C. Series (1989–90) of watercolor self-portraits exemplifies this duality. Loose marks in bright colors coalesce into abstract visages with only the faintest hints of facial features. Within each portrait, scaled to accommodate her sweeping gestures, repeated marks lend rhythm without settling into stable representational logics. The presence of the artist is more keenly felt through each stroke than through the visual itself.

Wilke began this series in the aftermath of her mother’s death from breast cancer, before her own cancer diagnosis in 1987. Despite the title—“B.C.” for “before cancer”—she continued these portraits after learning of her illness, up through the year before her death. Wilke reflects on her process: “I realized that what I had done in the last few days, because I had been quite depressed, was to make gestural layered watercolors of only my face, in which I took away my hair, creating circular patterns. But these portraits really became portraits of my mother, who had lost all of her hair from chemotherapy.”[1] Abstraction here lends crucial ambiguity, while repetition functions not as industrial perfection but as an embodied, ritualized act with affective resonance. In B.C. Series, January 14, 1989 (1989), a subtle ring from the bottom of a cup heightens the intimacy of this work, seemingly folded into Wilke’s quotidian routine.

The diaristic nature of the series is underscored by the dated titles: for example, B.C. Series, October 15, 1990 (1990). Each composition is thus a temporal record within the broader series as a mediation on change. While the all-black Untitled might seem to invite the projection of grief, the B.C. Series, together with Primary Life, reflects Wilke’s shift to incorporate brighter colors than ever before in the final years of her life. These works crystallize Wilke’s staunch commitment to artmaking as a generative act tied to the very vicissitudes of life. Gesture becomes persistence, charged with palpable vitality.

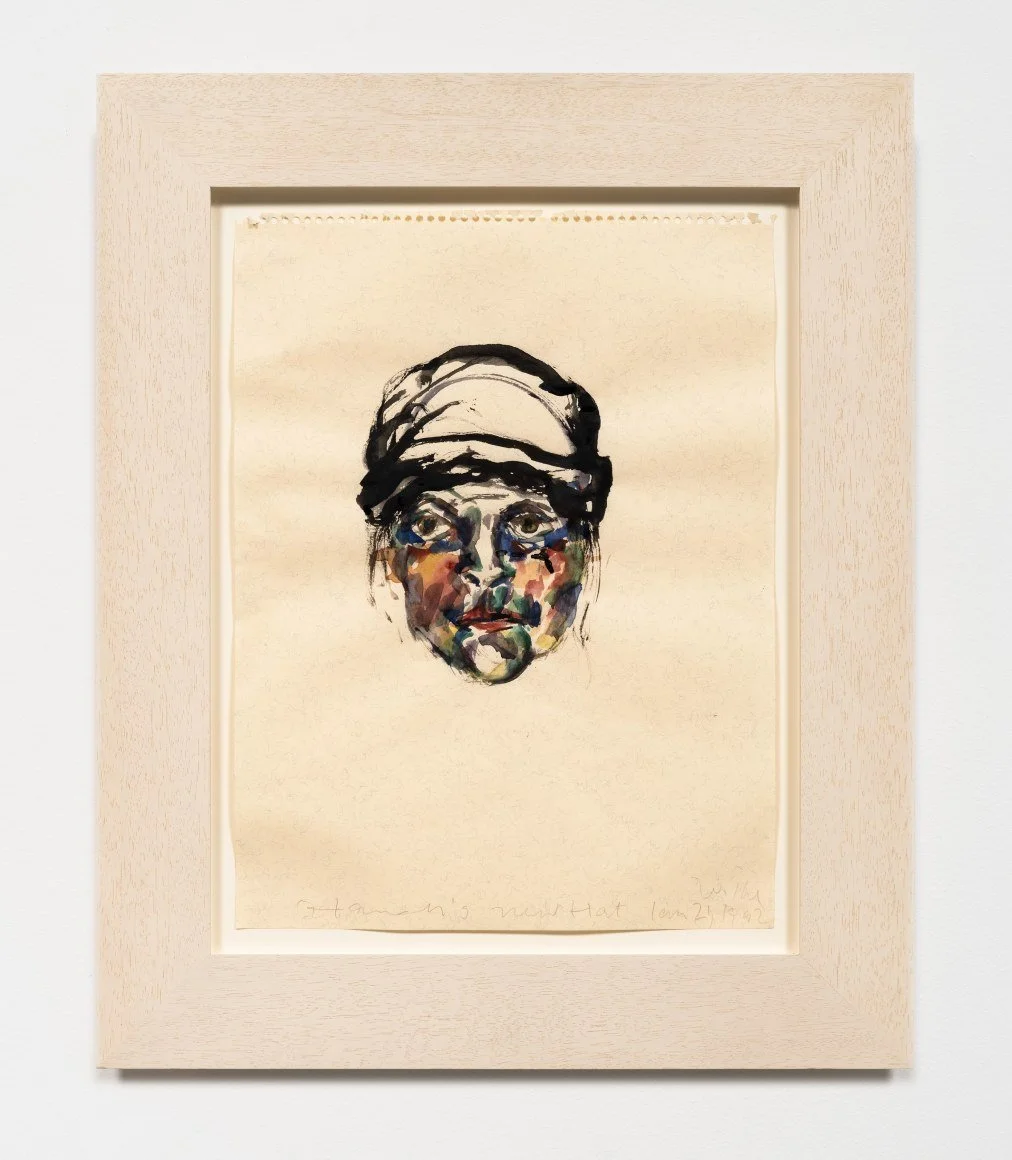

The exhibition’s most modest yet piercing work is Intra-Venus Face #2, January 21, 1992 (1992), one of many self-portraits made on notebook paper during hospitalization. Departing from the intense abstraction of the B.C. Series, we encounter the artist herself, who appears self-possessed, maybe even defiant, inscribed by her own hand. The title references both intravenous treatment and the Roman goddess of beauty, continuing Wilke’s interrogation of classical ideals of the female body through the assertion of her artistic agency. This series—which emerged alongside her more famous self-portrait photographs under the same title—channels the intimacy of the gestural, balancing vulnerability with a salient sense of corporeal presence.

Abstract Bodies offers a nuanced look at Wilke’s late practice by foregrounding her lesser-known portraits alongside her famed folds. This pairing encourages the ongoing critical redress of Wilke’s work, which was plagued with accusations of essentialism and narcissism during her lifetime. Throughout this intimate exhibition, abstraction serves not to distance the body, but rather lends corporeal intensity, through works oscillating between a sense of presence and absence.

Hannah Wilke: Abstract Bodies is on view at Petzel from September 4 through October 18, 2025.

[1] Linda Montano, “Hannah Wilke Interview,” in Performance Artists Talking in the Eighties (University of California Press, 2000), 140–41.