Bryce Kroll on a Probabilistic System of Perception

Bryce Kroll’s practice spans sculpture, drawing, and painting, investigating the creation of speculative forms derived from technological objects. His work considers questions of direct versus probabilistic perception, critically engaging with questions of what it means to create art in the age of generative AI and how to create work that is reflexive of its own systems of production and circulation. His exhibition Crap Shoot, which is oriented around a series of sculptures 3D printed in polylactic acid, is on view at Parent Company until March 7, 2026.

Alex Feim: Can you tell me about the exhibition title?

Bryce Kroll: The show is called Crap Shoot. The idea is basically a three-part association that making art is a bit of a gamble or a crapshoot, and craps is a casino game where throwing the dice is literally “shooting craps.” So shooting is something you can do with a gun, a camera, or a dice. With generative AI, the linear perspective you get with a camera or a gun has given way to this kind of casino-like, probabilistic vision of reality, where you’re seeing a statistical probability instead of a direct linear perspective.

AF: One of the reasons we connected was because we are both into AI and are skeptical of the mainstream discourses, but we are interested in using it in slightly incorrect and subversive ways. I’ve been playing around with it lately, where I’ll find a very nonsensical press release text, and then ask it to generate an image of the exhibition being described in the text. Then it does some crazy thing like making images of exhibitions that don't abide by the laws of gravity. It’s been interesting to do that and see that ChatGPT has this very specific idea of the gallery space where the walls are always a weird pinkish color. If I’m like, no, put it in a white cube, then Gemini seems to have a more fixed idea of a gallery as a space with white walls and a wooden floor. It will do these funny things where you don’t know why it’s making those decisions because you don't know what the training data are.

BK: Yes, it's a black box, where you’re seeing the gaps or problems with the training data, but you're also seeing an average or a blur of everything that the world statistically thinks about an exhibition. I see AI as something that enables you, without being an engineer or a scientist, to bracket aesthetics within constraints that define an input and an output. I think what we are getting at is its inability to act precisely as a tool, which is exactly why it’s useful in an art perspective, in that you can use it incorrectly. You can extract from it some element of surprise, but at the same time, it’s an extractive technology, and I purposefully named the series of works that are not made from AI “Real Extractions” for that reason, since they are playing off this extractive technology and perhaps have some extractive element of their own. An obvious one is the compounds in their pigments, which are listed in the titles rather than the material list.

AF: Real Extractions—what are they?

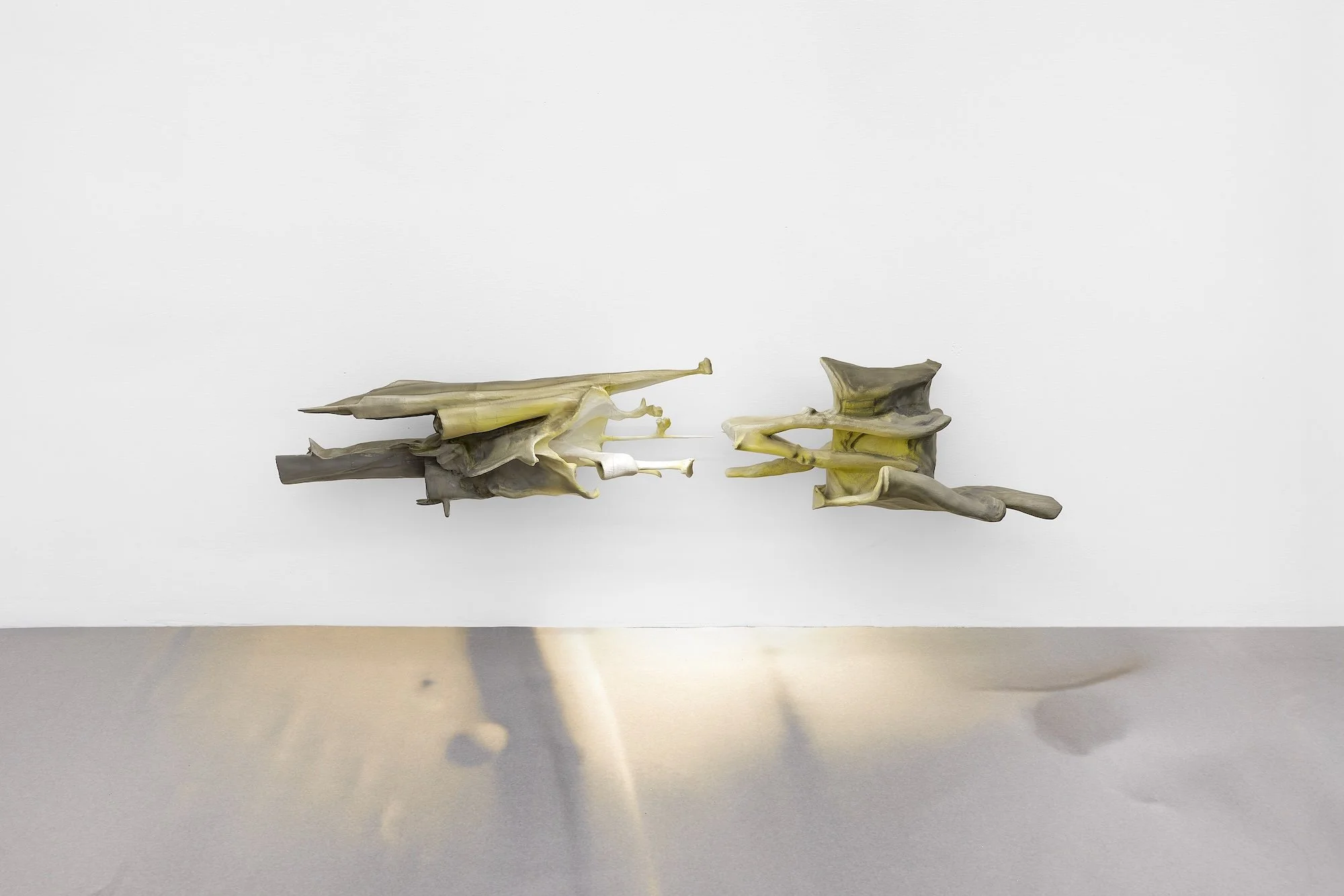

BK: The majority of my work now comes from sketches that I make without reference. I refine them, turn them into 3D models, and make them into sculptures, which then go on to inspire some paintings. The ones that I created from sketches are titled Real Extractions, and the pieces that I created using generative AI as a source are called Off Shoots, which is playing with the gun logic running through the whole show.

AF: It’s interesting that the forms come from drawings primarily. They do still look like something AI could have spat out with the melty, ambiguous, amorphous formal quality. The titles are sort of like a skeleton key, or a decoder device, to make the encounter something other than just the object or clue you in a little more to what you’re looking at.

BK: The show has the logic of an encryption scheme, a key, or just this one basic building block. I like to have a title that lets you decode what you’re seeing and then start to figure it out yourself. I’m probably more likely to choose an AI-generated output that resembles my work, but it is hard to tell which is which. When I work from sketches, I start with tiny thumbnails and blow them up using a pantograph, so there is an amplification of the idiosyncrasies of my hand, which is actually key to this question of authorship. I don’t think AI can replicate this, but I also don’t think I can come up with most of the stuff it does.

AF: Can you talk a bit about the show's layout and how you’ve engaged with the space?

BK: The works are hung very low, below a typical sight-line—I think it's because it’s the perspective from which I draw them. It’s putting you in the perspective of looking down—the bird’s-eye view of someone fabricating it. It feels to me that the problems of composition have just been taken from the page and transposed onto a 3D space. I’m typically responding to the space, treating it as a given image, and then dividing and using it in a way you would want in a sculpture or drawing. Then there’s a full wall-to-wall vinyl print on the floor, which corresponds to a painted, illusionistic glow on four of the pieces so they seem to cast light on the floor.

AF: How is this body of work an evolution from or a break with what you had made previously?

BK: The series I was working on right before this one was called False Echo, and it used a weed whacker as its source. I was feeding the weed whacker into AI, which resulted in paintings and images that ostensibly had the weed whacker as part of their reference but looked totally divorced from it. Hard Copy at Lubov was dealing with a fax machine, which I duplicated many times to create hard copies, as sculptures, and soft copies, as paintings, using it as a core form of technology where we’re losing bits of information in the process of its reproduction.

In this body of work, a shift occurs from direct perception to probabilistic perception, such that working in what might be called an expressive mode becomes capable of articulating something objective about the world, even if that's just my own subsumption within the system.

AF: You’re continuing to deal with these odd technological forms—the weed whacker, the fax machine, and now this kind of abstracted gun thing—how did you decide on these, or did they present themselves to you in some specific way?

BK: Until this show, they were all things that could theoretically be used for aesthetic purposes—you can send an artwork on a fax machine, landscaping is theoretically an aesthetic pursuit—so there was an attempt to create images of them in a way that their function was echoed in my production process. This show was a departure in that the gun theme emerged by surprise and was then confirmed by my thinking—it came to represent the abstract process of changing from a linear to a probabilistic perspective.

One thing I feel is often misunderstood is that I don’t think of my work as abstract per se. I think it's always attempting to picture something, which is, in fact, that kind of abstract system.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Bryce Kroll: Crap Shoot is on view at Parent Company from January 15th to March 7th, 2026.