Face to Face: November 2025

CLAIRE HENTSCHKER

What greets me at a studio storefront door on a chilly November night is nothing short of pure warmth. The space—LARPA, an artist-run studio and event spot co-founded by artist Claire Hentschker—is clearly arranged for gathering. A table of monitors, keyboards, and speakers ranging in modernity greets visitors at the entrance, along with comfy couches and large storefront windows. As you look deeper into the space, it gives way to a more traditional studio, with shelves of supplies, works-in-progress, and work stations.

Hentschker’s practice is inseparable from community, and LARPA feels like a clear expression of that. Events hosted here are proudly niche to the point of hilarity: Olympic livestream manipulations, high-concept, low-effort films, and a competition to build the “most evil computer” using malware. These events aren’t utilitarian or slick. They’re more akin to bizarre birthday-party crafts for adults. Claire finds pride in hosting events that are “disinteresting to 99.99% of people,” rooted in the joy of absurdity. The people who are there are wholeheartedly there.

Hentschker’s own work echoes these spirits of labors of love, humor, and anti-utility. Rhinestones and a UV nail lamp are found in her workspace, along with Sky Mall catalogues: her current dataset of choice. She sources the catalogues online, photographs the ridiculously luxurious yet outdated products, then puts them through an algorithm that guesses at their missing sides. The resulting 3D models—a hot-dog warmer, a toilet paper holder with iPod compatibility, an “ultra-finder” GPS with written directions instead of a map—are then 3D printed and ornately decorated with gems and nail art. These already impractical gadgets become even more indulgent relics. In removing all functional screens from these final objects, Hentschker challenges herself to eliminate the usual metric of success; it doesn't matter if these “work,” it only matters that they delight in a 2000s gadget fantasy.

During the pandemic, Hentschker’s work shifted towards bedazzling everyday food packaging: Capri Suns, Doritos bags, Pocky boxes, and even seventeen jars commissioned by Rao’s. She jokes about going from a 2016–17 Cartier residency, working with archival 3D scans, to the “low jewelry” of household trash embalmed in shimmer. Like her Sky Mall pieces, the tedium of these works emphasizes how consumerism eats our time while promising shine.

In Hentschker’s studio at LARPA, that joy in absurdity is ever-surrounding. She builds parameters through code and craft to invite people in. “Everything,” she says, “comes from a social interaction.” The untraditional, bizarro space glows with sincerity in the act of people making improbable things. With the goal of shared references and play, the results are limitless. As Hentchker puts it, “Nobody asked for this, and that’s good!”

LARPA events can be found at @larpa.mills on Instagram.

— Parker Ewen

MAYA MAN

If art strives to be a reflection of its time, what could be more contemporary than internet art? For most people, internet art signifies work that exists online. Still, the practice originally emerged as a response to, and appropriation of, a new social condition made possible by networked globalization and cyberspace. The premise was compelling when the internet was (if it ever truly was) a free and democratic space. Today, however, the internet has become an explicitly corporatized and monetized realm, where private companies carve out territories and enclose them as proprietary platforms. What happens within these bordered digital spaces is usually kept opaque, but we all know from experience that the reality algorithms shape in the digital realm spills over into—if not entirely produces—our physical reality.

Many artists working with digital media merely satisfy the whims and appetites of the algorithm. At best, those viral “art” videos with millions of views offer cool visuals; at worst, they are AI slop. How, then, does the artist navigate this oversaturated landscape of digital content? Maya Man, one of today’s most compelling artists working in digital media and internet art, may offer some answers. Man distinguishes herself through her critical, almost archaeological approach to the digital landscape. As she describes it, her practice traces how our “media consumption produces who we believe we are.” In other words, Man does not work within the algorithm's territory; her work excavates the algorithm itself, that black box which converts digital behavior into profit.

Consider one of Man’s recent pieces, A Realistic Day In My Life Living In New York City (2024), which hijacks the “day in my life” TikTok trend. The work was the first commission for the Whitney Museum’s Internet art program, On The Hour. Running live on the Whitney’s website, at the top of every hour, 24 times a day, the work features a quote from a TikTok documenting a “day in my life in New York City” alongside a flow of the video’s comments. By undermining TikTok’s essence as a hyper-videographic platform and reducing the trend to bare text, stripping away the advertised commodities that typically occupy the influencer’s frame, Man neutralizes the performance of (re)presentation. As mere words, the trend appears absurd: unending descriptions of a life lived only to become social media content.

Recently, Man’s practice has expanded to consider the advent of generative AI, which represents the ultimate interlinking of algorithms and “realistic” life. StarQuest, her latest body of work, features 111 AI-generated dance scenes that restage the aesthetics and theatrics of cult reality television series Dance Moms. Two weeks ago, Triple Canopy and Feral File co-presented her installation and performance-lecture at Gibney Dance’s Agnes Varis Performing Arts Center downtown. StarQuest is currently on view on Feral File online.

— Yonatan Eshban-Laderman

MINKU KIM

An abstract symphony of ivory birds, gently twisting trees, and slender moons compose the world of Minku Kim’s paintings. In his TREES (2025) series, Kim references his own iPhone photos of New York City’s various public parks to reimagine our municipal green spaces as fantastical scenes plucked out of a storybook. In works such as Spring Trees (2025), Kim’s fluid geometric forms invite personal interpretation: where some people see a cloud, others will see a heart. Nevertheless, what appears to be a loose spontaneity in Kim’s compositions is actually the result of firmly conducted precision. He pays exactingly close attention to striking a harmonious balance of light, texture, and form.

The color blue permeates Kim’s canvases, notably in his current series Sarang (Love) (2024–25), which he began after his recent marriage. When I ask him why blue in particular, he says, “Blue is my favorite and most versatile color. Picasso’s Blue Period is a point of reference, but where his blue felt introspective, I aim for a blue that remains both profound and quietly optimistic.” He continues: “I wanted to work with blues because both the word and the color itself evoke a sense of infinite depth—yet could also be a compressed, meditative space. The work carries potent references to music and art history, which I weave into my own visual language.” Upon this remark, I took another look at Sarang No. 6 (2024–25) displayed on the wall of his Brooklyn studio. The color palette is limited to varying shades of blue, with sparing usage of soft greens and a single speck of pink, yet Kim skillfully manipulates the color in all its iterations, from pale azure to deep cobalt, to create an illusion of pictorial depth upon the flat surface of the canvas.

There is an unmistakable joy and optimism that resonates in Kim’s art, and one can see that his practice is a labor of love in a myriad of ways—he is inspired by his love of nature, the love he feels for his wife, love for the act of painting itself. Kim spends hundreds of hours on each painting, often revisiting them after a short period of time to make subtle adjustments. “You might spend two or three months working on a single work, but most people spend only about ten or twenty seconds looking before moving on to the next one,” he muses. “Still, when the work truly connects with someone, it has the power to transform their life. That’s the magic of art, you know?”

— Colleen Dalusong

FRANK WANG YEFENG

On my way to meet Frank WANG Yefeng, I passed a mural of an octopus. It felt like a perfect teaser for Yefeng’s interdisciplinary practice, defined by playful, monstrous forms and interstitial subjectivities. The artist’s studio similarly exhibited his disinterest in categorical rigidity, as rows of paint tubes scatter beside handfuls of rice crackers.

A single wall—what he calls his “meditation wall”—is lined salon-style with paintings depicting everything from hybridized cephalopods to nebulous rings. These painted creatures recalled Yefeng’s ongoing project, The Levitating Perils (2022). Drawing on the historic legacies of racial caricature and the 19th- and 20th-century panicked ideology of the “Yellow Peril,” Yefeng blends archival text and images with digital animation and sculpture to interrogate colonial fantasies of animality. In The Levitating Perils #2 (2025), made for the Whitney’s On the Hour project, Yefeng’s animations perform a digital hijacking of the site with their monstrous, inscrutable forms.

It is easy to describe Yefeng’s work through the language of hybridization, but this feels insufficient. Rather than presenting a strict set of ontological dichotomies, he probes the failures of taxonomic fixity. His 3D animation Groundless Flower (2025) examines these subjective oscillations against the backdrop of the Gobi Desert. Trotting, vegetal beings cross the vast landscape as translucent clouds drift alongside them. The 2D and 3D do not simply conjoin; they reunite in a kind of neo-materialist blossoming. For his recent commission for the High Line, Groundless Flower – ཨ (2025), Yefeng expands on the previous video, collaging landscape imagery with Chinese mythology, such as the story of Pangu (盤古), the deity of creation. Turning down the volume on the video, Yefeng asks me, “How do you find subjectivity as an in-betweener?” I realize that Groundless Flower – ཨ poses the same question in metaphor: how do you find footing with no ground?

Yefeng uncovers various forms of subjectivity, as mediated through the tentacled mechanisms of the internet. We scroll through images of his project Avatopology (2023), a portmanteau of “avatar” and “topology.” Through an online marketplace platform, Yefeng commissioned freelancers to create 3D modeled portraits of himself. Though the prompt sets up an ostensibly biographical tone, what unfolds instead is a global network of intimate exchanges and a window into the techno-feudalist gig economy. Across several of his works, the artist interrogates the language that plagues internet relations, such as the hyper-romanticism of the buzzing phrase “digital nomadism”. “We don’t really understand what this phrase even implies, and its underlying privilege,” he explains. Yet, he also finds productive forces in the broader philosophy of nomadism as a way of thinking through ontological instability: “Nomadic becoming is less of a physical process, but a kind of thinking.”

For Yefeng, erosion is not only an environmental mechanism of destruction, but also a process of becoming. Just as sand in the Gobi Desert gradually reshapes the form of a lonesome rock, the artist explores the passive and active forces through which subjectivity is produced and continually transformed.

— June Kitahara

CHRISTOPHER GAMBINO

Sitting on the emerald-green painted floor of Christopher Gambino’s studio, streaked with resin, surrounded by flattened bits of trash and indeterminate stains of who knows what else, I feel slightly uneasy. Imagine the dressing room of a movie star after a tantrum: wigs matted, chair legs bandaged in pantyhose, cracked champagne bottles, a dead handler, and sequined debris everywhere. What steadies me are Christopher’s gravelly, timeworn voice and kind, bedeviled eyes.

“Should this fantasy become reality, I want to do something really insane. I’d love to have a big crash-out and throw my phone at my assistant,” Christopher laughs maniacally.

Gambino trades in delusion and spectacle. The studio—a crime scene, a workshop, a shrine—becomes a site for transformation. “It’s about actualizing the path from normal life into the transcendent: the red carpet, the flashing lights,” Gambino explains. “For some reason, I just feel like I need a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.” I ask if that’s even possible for an artist. Gambino laughs: “No. I’m literally just asking for attention.”

Around us, tattered shoes, resin-coated nylons, and dismembered furniture coalesce into uncanny portraits of the body. Chair legs become legs sheathed in pantyhose with ill-fitting red soled heels dangling off where feet should be. It’s a move so simple and cheeky that it’s devastating, harkening back to the surrealist greats. With their parts splayed and bound, the sculptures suggest figures caught mid-gesture—always performing, always receiving, and sometimes giving.

Across the studio and within each assemblage lies a mélange of styles: mass-produced mid-century facsimiles, Art Deco decoys, and nouveau crystal vases—one of which, Christopher tells me, will be smashed on site at an upcoming show. I can’t help but notice the anachronisms and inconsistencies, so I press Christopher: “What time period are you referencing here?”

Gambino’s neck snaps sharply in my direction. “Well, that’s the question on everyone’s lips these days!” They laugh. I push again: “So… what time period?” Christopher grins, a smile flashing through a curtain of jet-black hair. “It’s our time.”

For Gambino, the mismatched woods, the faux finishes of cheaply made vintage furniture, and the collision of objects representing different eras of American consumer desire all point to a contemporary condition—one where the facade of aspirational wealth has been shattered and literally trashed. Yet there’s no love lost. In fact, there’s more love found. Each sculpture, Gambino tells me, carries its own backstory: an anecdote or incident borrowed from the tragic glamour of life.

Gambino’s installations exist in this strange space, between action and aftermath, where desire curdles into exhaustion and grandeur collapses under its own weight. Through these assemblages, riddled with loss, desire, and fantasy, Gambino manipulates the relationship between object, subject, and assumption.

What appears to be a body bending in submission might instead depict someone kneeling to pick up an earring. Who’s the voyeur here—Christopher, me, you, or the objects? What remains on the eye is a beautiful, anxious, and ruinous scene. As I leave the studio, I notice one sculpture huddled in a corner as if scolded, a performer exiled to the edges of a stage. The world, it seems, is unrelenting and unkind to its stars.

— Jesse Firestone

OLOF MARSJA

In the work of Olof Marsja, assemblage and contemporary materiality meet traditional crafts rooted in Duodji.[1] The artist describes his practice as stemming from the experience of a fractured language and cultural identity. Like so many other Sámi people, Marsja does not speak the native language of his ancestors—a tragic result of a dark part of Nordic history, where nation states oppressed the countries’ Indigenous populations. He expresses this detachment as “an unbroken line of Sámi that has been severed within me.” He continues, “The colonial wound aches in both body and soul. It ended here. It became a break—a point of silence.”

Marsja currently lives and works in Gothenburg, Sweden. He was born in Gällivare on the Swedish side of Sápmi and started out studying Garraduodji [2] at the Sami Education Center in Jokkmokk. Following this, he graduated from Konstfack University of Art, Craft and Design in Stockholm with an exchange semester at the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki. With this cross-disciplinary background, the artist aims to create a sculptural language that speaks with remembrance of those who walked before him—to honor those who have passed—while also looking forward.

What has emerged is a language that carries the form and grammar of in-betweenness. This encompasses different understandings of time, combinations of materials and techniques, and moving between the personal and the collective. The sculptures become hybrid entities that evoke questions of identity, heritage, and the body’s presence within a sculptural landscape. And while certainly possessing monumental spatial presence, Marsja’s works ask to be observed with the same attention to detail as they have been made.

It has been a busy year for Marsja. He recently completed the exhibition To carry this body of an animal forth at 1646 Experimental Art Space in The Hague. This marked his first solo exhibition outside of Scandinavia and presented a combination of new and older works. The team at 1646 encouraged his wish to try out new paths in his practice, which resulted in two sound pieces that played through horn-like sculptures made of glass and birch trumpets. In addition to playing with language, the works put forward the mythical soundscape that the artist imagines his works to dwell in.

Earlier this year, Public Art Agency Sweden commissioned a work for Hanaholmen–Swedish-Finnish Cultural Centre’s 50th anniversary. The sculpture, Light Tracker [Northern Sámi: Čuovgga guorri] (2025), will be officially inaugurated on 2 December. Marsja is also currently part of the group exhibition A Time for Everything: 25 Years of Contemporary Art at Scandinavia House in New York until February 2026, celebrating the cultural center’s 25th anniversary.

— Marthe Yung Mee Hansen

ERICA BAUM

Erica Baum is getting baroque. As an Upper West Side teenager haunting Colosseum books, she looked for experimental new releases from Grove Press or New Directions. As a Barnard College anthropology major, she encountered Japanese poetry and was deeply struck by its ability to isolate weightless yet evocative images. (It’s no coincidence that her narrow Soho loft feels like a book-lined airship à la Hayao Miyazaki.) As an aspiring young painter and collagist with a day job at the Parks Department, she was tasked with installing Social Realist murals, which put her off painting. But another part of the job, documenting the work of civilian volunteers, got her started with a camera.

After getting herself up to speed on photography with classes at SVA and library books, she earned an MFA in the discipline at Yale in 1994. “I felt I had to commit to something,” she told me. There, she discovered her first muse in the form of half-erased blackboards. Her deadpan photos of these intentionally temporary relics of thinking and speaking are as easy to read—and as discreetly profound—as moonlight on a wintry lake or William Carlos Williams. Like haiku, they highlight a small-scale mortality to evoke a larger one. But instead of changing seasons or the inevitability of death, it’s a hastily-scrawled word like “SIMBOLISMO” bringing out the fleeting, performative, accidental nature of even the most authentic of human creative expression, which, when you think about it, is pretty funny.

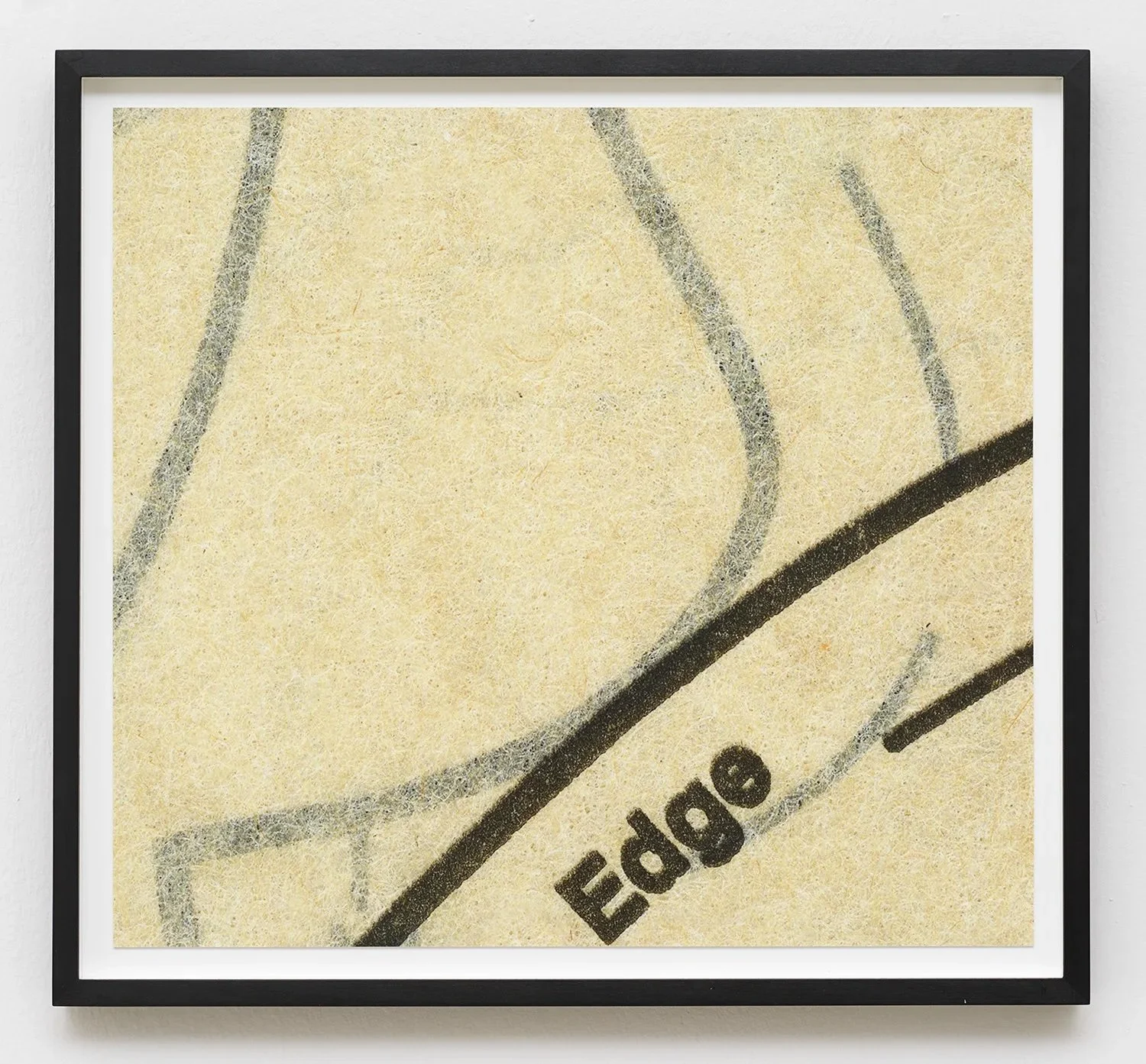

Baum’s incisive but indirect humor and her eye for subtle beauty developed further in series like Dog Ear (2009–) and Card Catalogues (1996–98). In the former, dog-eared pages of books she’s reading, one against the other, become elegant little compositions of concrete poetry. In the latter, the accidental juxtapositions of library organization become loving deflations of Western culture, as when a category title like “Reason” or “God” sits over a gray-tone landscape of humble index cards, or become mordant revelations of our collective unconscious, as when “Subversive Activities,” slightly out of focus, sits just above a crisp “Suburban Homes.”

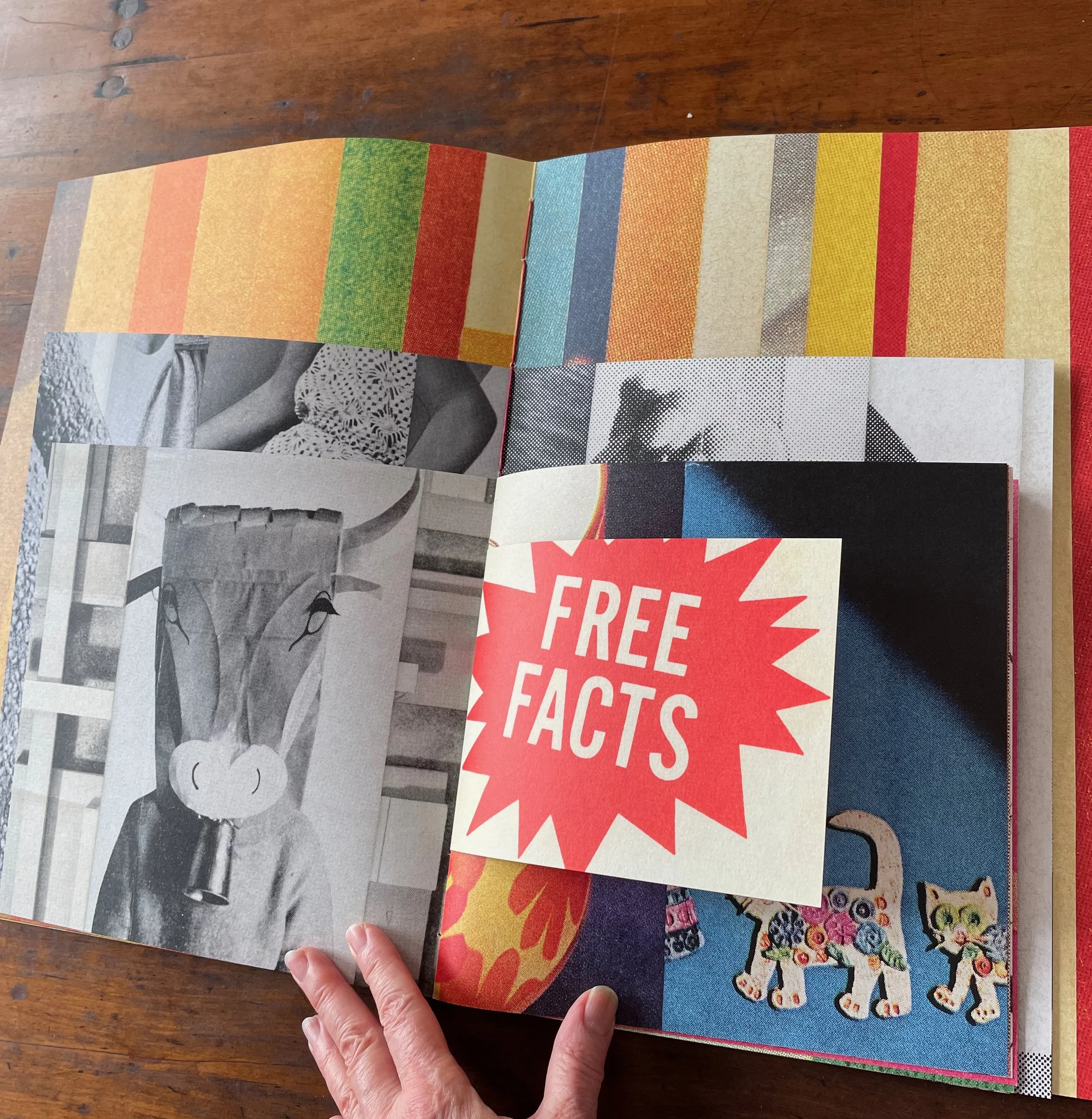

Even as she was making minimal, restrained work, though, Baum’s youthful interest in color and collage lay waiting to return. In the windowless square studio built into the center of her loft, Baum showed me stacks of the gaudy old pulp novels she uses to make her more recent Naked Eye (2008–) photos—loud, vertically-striped express trains through the history of advertising and cinema. And her new exhibition at the Eastman Museum in Rochester is filled with gloriously colorful new works from her Patterns (2018–) and Fabrications (2023–) series, which use vintage textile patterns and magazines to create photographs that sit somewhere between early op art and late Matisse. In Patterns and Fabrications, Baum also intervenes more actively in her materials, cutting and arranging in a way she never would have done on a blackboard. But it’s all right; at this point, she knows how to protect an accidental meaning, even when she’s staged it herself.

— Will Heinrich

TONYE EKINE

One of the wonderful achievements of Tonye Ekine’s practice is his juxtaposition of opposing contexts to create a sense of the real. His works revolve around Ife masks from Western Africa, specifically, Nigeria. Each painting is an invitation to engage with what lies beyond the mask. In creating a space for conversations around his paintings, he has opened doors in multiple directions—yet none of these conversations address easy topics.

The masks conceal the faces of all human figures in his paintings, whether of African origin or not, creating a sense of uniformity, yet equality is not an evident characteristic. Do these paintings transcend race, or do they reposition our perspective when it comes to recognizing race? Each mask goes back to a land and a history that may or may not have a direct connection with the character in view, but has incredible significance to the artist. The weight of a bronze mask cannot be borne equally or equitably by all, and the audience must recognize the disparity in power, no matter how similarly the characters dress or how they share the space within Ekine’s canvas.

There is a sublime somberness present within these paintings, parallel to a stark and vibrant color palette. At their core, they bring to the fore a sense of something unsettling—and that is because colonialism is nothing less than an inhuman and unnatural perversion, and to paint or talk about it is to engage with that tension. The image of society that Ekine captures is one populated with people catering to a Western structure, conforming to its attire, gestures, and environments, while remaining rooted in African heritage. It is not a story that belongs to Ekine alone, but to all those who trace their ancestry to lands occupied and dominated by colonizers.

The artist begins to tell a story that breaks free from the visual and gets the audience involved in a dialogue, one that Ekine himself is a part of. How does one recognize and learn to adapt to the weight of one’s cultural heritage? His works are entryways to questions of immigrant experiences and diasporic circumstances that have been central to so many discourses over the last century. This has to do with both historical burden and contemporary identity: a constant push and pull between waves of globalization reducing every culture to a lesser representation of the consumerist West and the oppositional monolith of conservative nationalism. The ideal position somewhere in between is where a conversation with the artist must take place.

Ekine’s practice is a decolonial tool in an otherwise complacent world. One that wants to fight against the aggressive normalization of the decay that centuries of colonialism have sown into the Global South. His push for a dialogue is a push for the revitalization of all cultures imbalanced by the greed and wanton violence of extractivist colonial forces.

— Abbas Malakar