Computer Dreams: On Information and Images

There is the image, and there is information. Or so goes the art historical orthodoxy—after minimalism and pop, the art object underwent a “dematerialization,” to use historian Lucy Lippard’s parlance, shedding its finite, fetish aura to transmute into “action” or “idea.”[1] It was the dawning Information Age, when America was rapidly deindustrializing and financializing. Our national culture, theorist Jack Burnham noted in 1968, was in transition from “an object-oriented culture to a system-oriented culture,” and we were developing a national arts to match.[2]

Hence the rise of what Burnham calls “unobjects”: environments, illuminations, data-sets. It could be called conceptual art, or systems art, or installation, or process, or a thousand other monikers. In his 1970 Jewish Museum exhibition Software, Burnham highlighted pieces like Hans Haacke’s News (1969/2008), in which teletype machines print out live local and national news, or Les Levine’s televisual exhibitionist pieces A.I.R. (1968–70) and Wire Tap (1969–70), which allow viewers to surveil the artist working in his studio or speaking on the telephone.[3] Many conceptual, computational artists of the era worked in corporate- and government-sponsored art incubators, including Bell Labs’ Experiments in Arts and Technology, LACMA’s IBM and Lockheed-funded Art & Technology, and MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies, all founded around 1967. These programs fostered a conceptual art focused not so much on image, but rather on information, interaction, and procedure. This art was then legitimized in the museum, with shows like Software, MoMA’s Information (1970) and LACMA’s Art & Technology (1971).

In the decades between this epochal art-tech boom and the levee-break of Internet and Post-Internet art, digital art seemed inescapably siloed into the corporate or conceptual. Art, when faced with electronics, could ally itself with industrial systems and engineers, or otherwise evaporate into the ether—become, returning to Lippard, de-material.

But there are other histories, other modes of development. In their exhibition The First Circle: Radical Humanism, curators Claudia Hart and Natasha Chuk chart a compelling alternate history of digital and computer-based art. The works here, which span from 1974 to 2022, are united in their resolute focus on the representational and auratic. The gallery is full of chirping sprites and staring heads. It feels, strangely, alive.

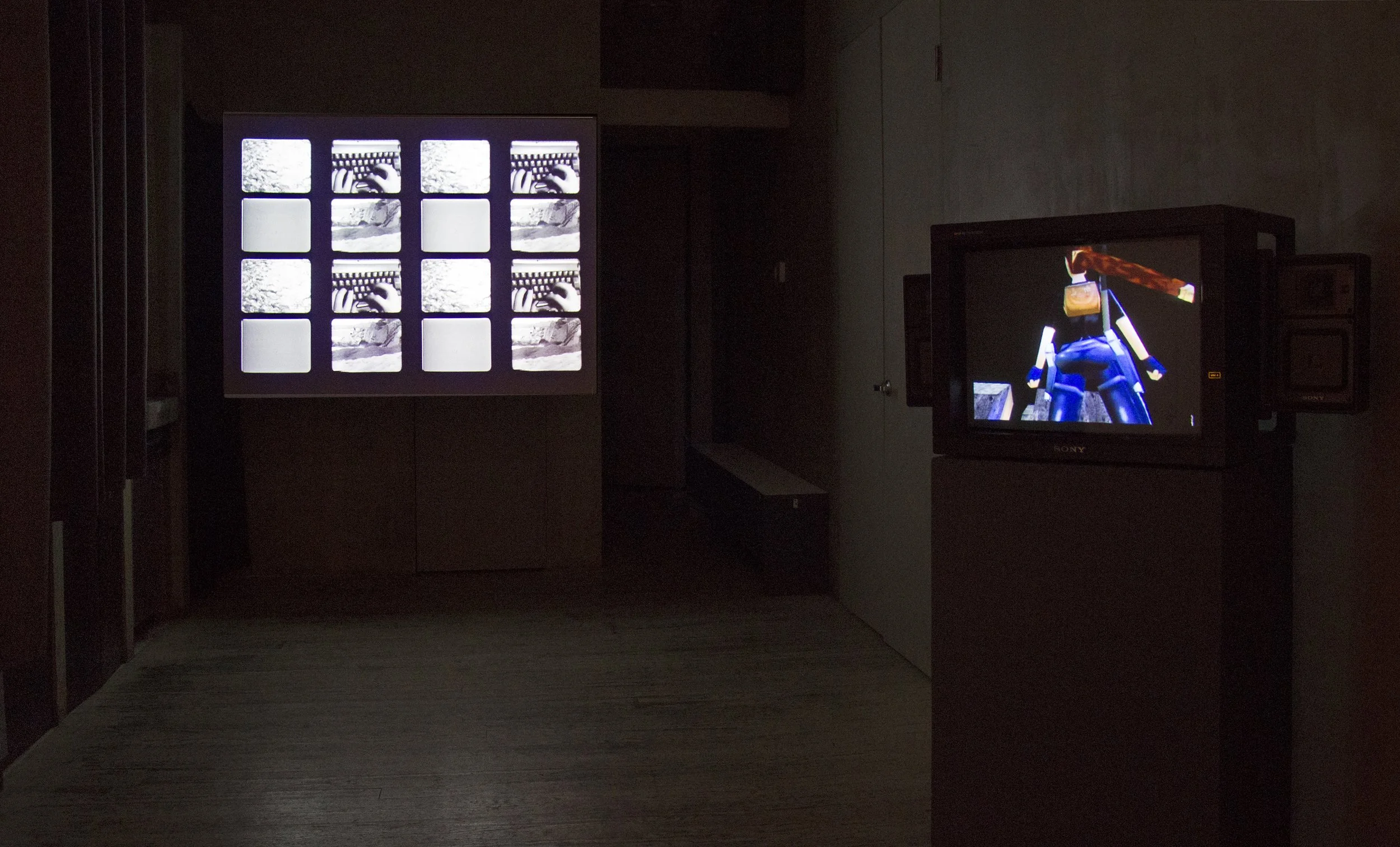

A useful starting point to organize your viewing is in the back room, where Paul Wong’s multi-channel video Earthworks in Harmony (1974–2024) plays on the far wall. Here, shots of hands molding a pile of sand and grainy blazes call to mind “dematerial” arts of that earlier era, like Ana Mendieta’s landscape interventions or John Baldessari’s Cremation Project (1970). The display, however, is reminiscent of Nam June Paik or Gretchen Bender: an overwhelming array of competing and contrasting images, visual data vying for attention.

Nearby is Peggy Ahwesh’s She Puppet (2001), a truly captivating video piece recorded within the Tomb Raider video game. The player character, Lara Croft, is subjected not just to in-game torture, being torn apart by tigers, piranhas, and gigantic vultures. She’s stuck—in narrow passageways, in freezing or scorching temperatures, and especially in the gaze of the game’s camera function, which Ahwesh uses to invasively ogle the character’s famously exaggerated proportions. This is machinima-as-détournement, an exploration of what logics underpin these mass-distributed digital worlds, and who they’re aimed at stimulating. Decades of technological development lie between this piece and Wong’s, and the staging feels instructive: this is where we’ve landed, a fetish-doll torture trap?

Back in the main gallery, Granular Synthesis’s SWEETHEART (1997) and Claudia Hart’s Channeling Medusa (Illumination) (2015/2025) form an unsettling duo. The former is all glitching head-bobs and grinding bass, seemingly stuck, like Ahwesh’s Lara Croft, in a hell of looped torment. The latter drifts lazily between dozing and waking, though I swear it felt like the holographic face cracked its eyes when I walked past. These works have a definite presence: they writhe, wriggle, and perform, with seemingly varied levels of resentment.

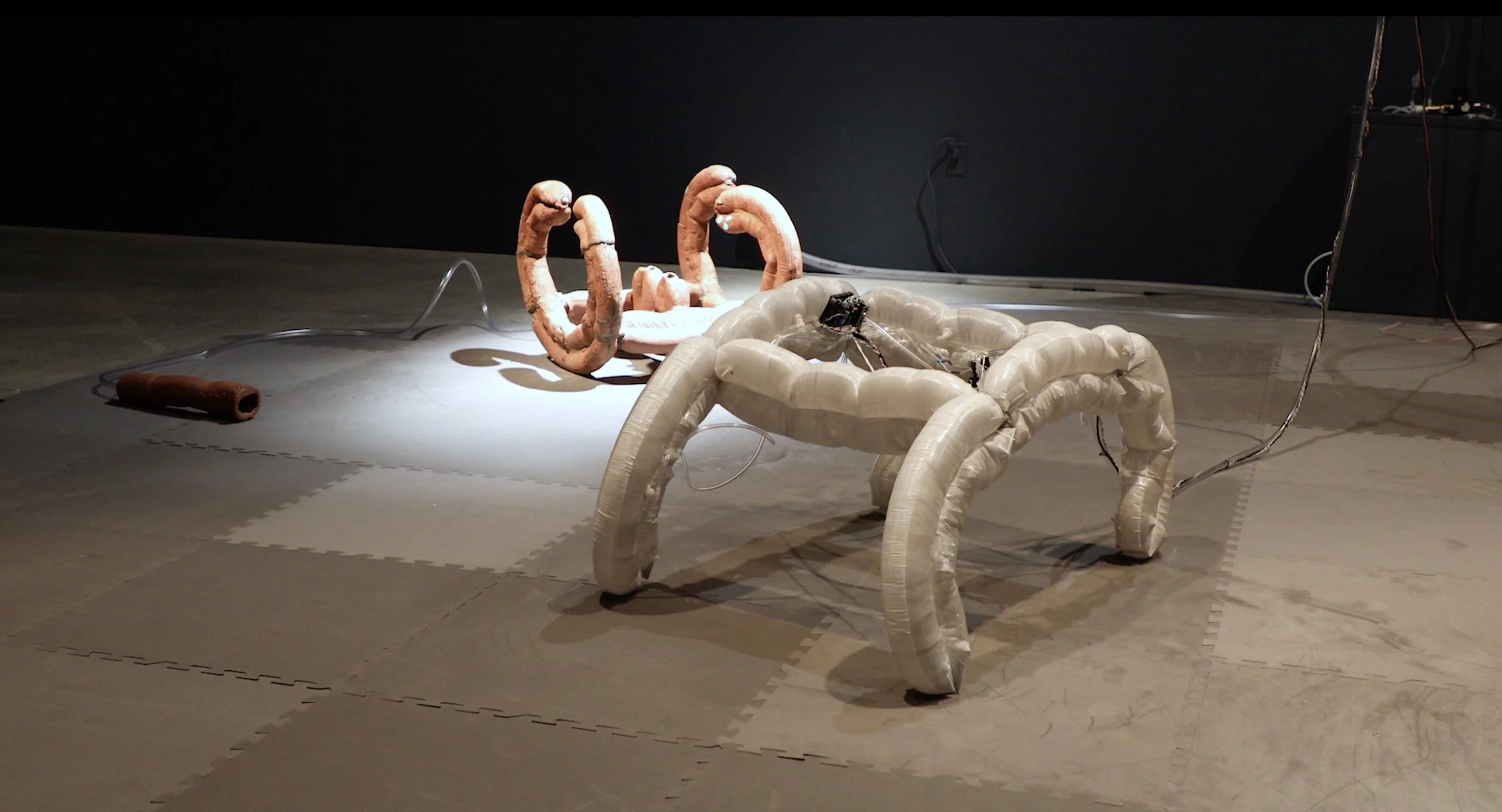

This theme carries over to an equally troubling array of works along the same wall. In Chico MacMurtrie’s Dual Pneuma (2024), digitally rendered soft sculptures bend and quiver in an empty gallery space. Again, an undercurrent of bondage—their contortions feel painful, but also exhibitionist. So does Michael Rees’s Putto 2.2.2.2. (2008), which pairs a cast bronze scorpion-homunculus with a flickering video of the same form, flexing and twitching in silhouette like some Silent Hill boss undergoing shock treatment.

You’ll notice my persistent personification of the forms and images on display here—this effect is surely intentional. Hart and Chuk emphasized to me their focus in curating works by image-makers with no formal engineering training—artists who came to computers as an extension of their existing pictorial or performance practice. These artists, Hart says, “resist corporatism through practices based on the body, and through a personal and expressive orientation.”

The tenor of these works is not uniformly liberatory. So many of them convey a creeping sense of confinement and constraint, like Les LeVeque’s Doppler Beaming #9 (2022), which alternates its display between a string of non-sequitur vocabulary and a heat-mapped still-life of a tabletop vase. It feels like the code in these works is rattling its own cage, and the result is a highly effective antidote to the bland branding of all technological development as utopic. In fact, amid the exhausting ongoing debates over whether recent AI technology can possess anything like genuine intelligence, I found that works like She Puppet and Putto 2.2.2.2 felt bracingly alive. They elicited in me something like sympathy.

Not all the works on display partake of this strategy. These include Nancy Burson’s frankly hilarious diptych Baby Marilyn and Baby Elvis De-aged Simulacra (1988), Jennifer Steinkamp’s Fruit Ninja/screensaver/statement Impeach 1 (2019), and Julia Heyward’s point-and-click drainer-aesthetic CD-ROM adventure game Miracles in Reverse (2002). Some of these works are interesting as historical nodes; few have the same visceral impact as the works I’ve mentioned above.

To return to that original corporate-conceptual paradigm, the works in The First Circle: Radical Humanism excel at making visible a persistent, parallel history of digital art, one that squeezes outside of data sheafs and prods at mass-distributed forms. These pieces are resolutely material. They insist upon their objecthood, daring the viewer to look, interact, and poke back.

The First Circle: Radical Humanism is on view at Microscope Gallery from July 17 through August 16, 2025.

[1] Lucy Lippard, “Escape Attempts” in Six Years: The Dematerialization of The Art Object from 1966 to 1972 (University of California Press, 1973), vii–xxii.

[2] Jack Burnham, “Systems Esthetics,” Artforum 7, no. 1 (September 1968): 30–35.

[3] Jack Burnham, Software (Information technology: its new meaning for art), exh. cat. (Jewish Museum; Smithsonian Institution, 1970).