Zoe Leonard: “Display” at Maxwell Graham

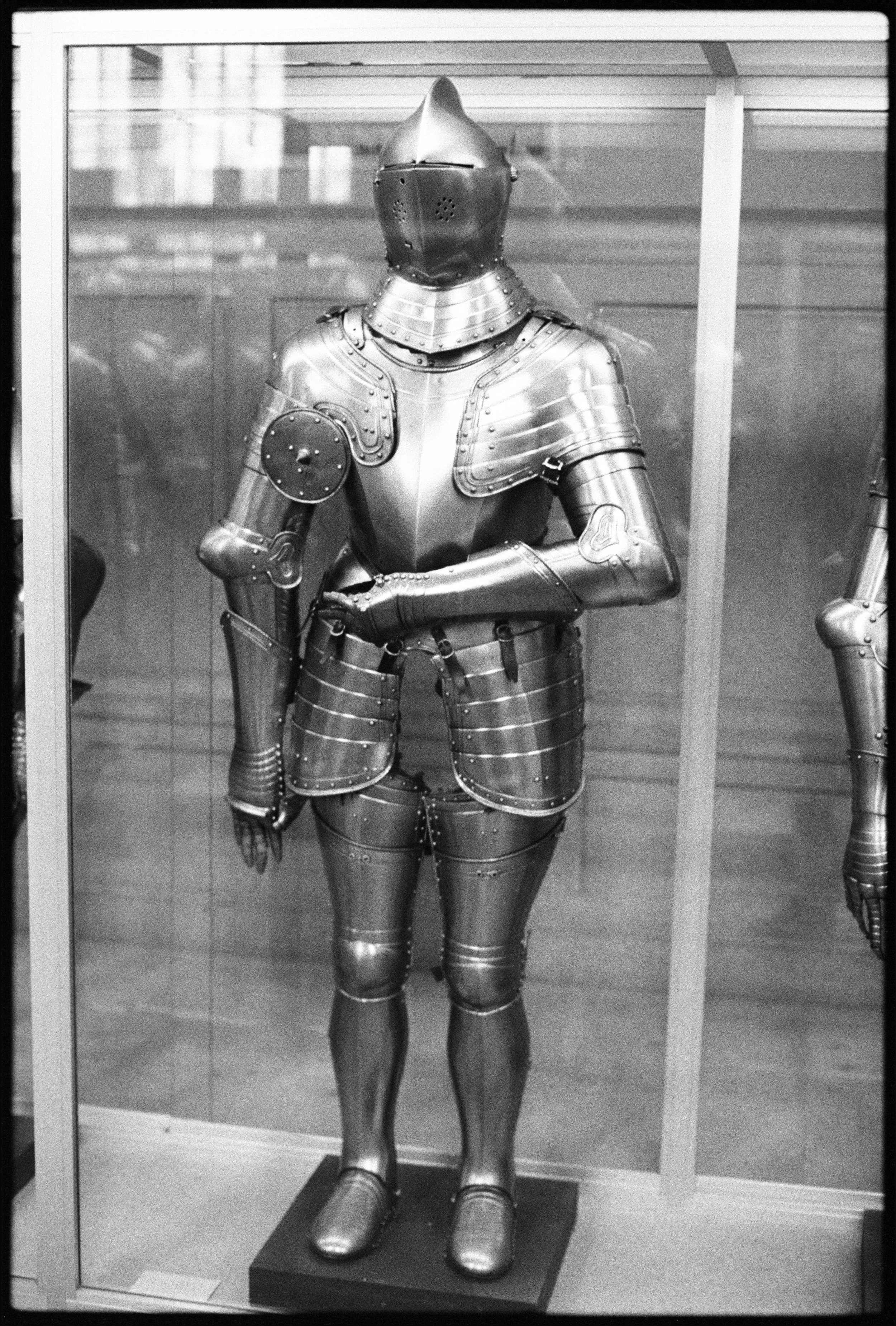

Despite consisting of just six silver gelatin prints and a stack of postcards, Zoe Leonard’s Display took two weeks to install. Leonard must have tested the photographs—five of medieval armor and one ancient Roman chest cuirass, all unframed and pressed against the wall with plexiglass and L pins—in multiple locations and varying arrangements on the walls at Maxwell Graham’s Lower East Side gallery. The result is dizzying; Leonard’s spatial rigor pays off in a show whose minimal expression, almost guileless in its palimpsestic layering of symbols and historical registers, belies a vertiginous attention to detail.

Several entry points present themselves all at once: the armor, their display, the noise of the analog film, the full-frame prints, not to mention the historical leaps through which the artwork operates. The negatives were taken between 1990 and 1994 and printed this year, The armor depicted is from the 14th to 16th century (though the chest cuirass is from 300 BCE), and the photographs depict the armor on display at the Musée de l'Armée in Paris, conjuring the temporality of a museum’s permanent collection, endless and empty like the armor itself. Reprising similar themes in Leonard’s previous works which interrogate apparatuses of knowledge and display, the contrast between the emptiness of the armor and the projected strength of the steel panoply becomes a key metaphor for untangling the themes of Display.

The show’s various connections are presented to us in a parallax view with the historical caprices of our moment. Before high-velocity bullet-based weapons made them obsolete, the majority of European national armies were made up of so-called “men-at-arms” swathed in gaudy plates of steel. Thus, the knight became the symbol of conquest and coercion; enter the hyper-masculine hero, knight in shining armor, defeating the dragon and saving the princess—a symbol that persists to this day.[1] Leonard’s framing flips the storybook archetype, presenting the suits instead as metaphors for state-sponsored bullies, their masked faces and militarized garb evoking the anonymized violence being committed against undocumented people by ICE or the raw aggression emblematic in the American government’s renaming of the Department of Defense to the “Department of War.”

Yet armor remains an aesthetic vestige of a past era, and their status as objects of display, cloistered from the world, elucidates a transference between utilitarianism and decoration common in the ideological abuse of historical symbols. This is evident, for example, in the movement of camouflage from a utilitarian military technology to a fashion trend. In the museum, armor becomes monuments to histories of conquest: nationalist symbols that mix decoration with a nostalgia for violence. Connecting nationalism and decoration, the Marxist politician and theorist Antonio Gramsci wrote, “[t]he ‘nation’ is not the people, or the past that continues in the ‘people,’ but the set of material things that recall the past… a ‘distortion’ precisely because it has become a purely decorative, external and rhetorical motif.”[2]

A labored humanity has been breathed into these empty hulks by institutional caretakers—curators and conservators. Their arms are bent at slight angles as if mid-gesture; one looks as though it’s about to launch into a deep bow. Leonard’s photographs capture this strange subjectivity; despite their blunt symbolism, Leonard’s camera lands on the men-at-arms with humanity. Accordingly, much thought has gone into the scale of the photographs. The suits of armor are relatively the same size in each print. Even the scale of the lone cuirass, depicted in the smallest photograph in the show, roughly approximates the scale of those on the full suits of armor. In its careful arrangement, the show suggests a double simulation: one of being surrounded by intimidating, anonymized—yet distinctly anthropomorphic—figures of repression, and another of standing at the center of the display room, contemplating relics in a space outside of time.

In Leonard’s other museological work taken around the same time, she explores the institutionalization of female sexuality through photographs of historical objects of sexual control, such as Chastity Belt (1990/1993), which Maxwell Graham presented as part of its booth at Art Basel in Switzerland this year. In contrast, the armor in Display is conspicuously desexed—the molding on the wall behind is visible through the holes left absent in their crotches. Viewed in relation to one another, these two bodies of work critique the notion of the universal body in which any description of a body is circumscribed by the body of the dominant class and is given identifying terms only when it deviates from that norm. In his 2002 book Publics and Counterpublics, the literary critic Michael Warner gives the example of heterosexuality, which is almost never named and always assumed unless stated otherwise.[3]

Leonard has been active in art and activism since the 1980s, and much of her work has blossomed from a photographer’s compulsion to photograph, document, collect, and archive. The decision to excavate old negatives from her archive for exhibition today is not cynical. It functions as an operative conceptual component of the work itself (evident in that each work is dated twice on the checklist). By communicating these concepts aesthetically through images found in the archeology of her own practice, Leonard implicitly argues for a material orientation towards history in which forms of violence existent in past historical eras—this includes all the periods the work leaps into—return today, guised as new questions and in new aesthetic forms.

Display is an exhibition about history and its interpretation. It insists that the looming fascism that we face today cannot stem from a political aberration but is instead a result of a historical process upon which it is contingent. On the way out of the exhibition, a stack of postcards sits neatly beside the door. Close observers will notice that the image of the armor on the postcards is different from the images on view. In it, Leonard herself is reflected in the glass, superimposed onto the oafish brutes. She appears like Walter Benjamin’s angel of history, facing the past, camera-armed, capturing what she can of the growing pile of history while we are blown by a storm, that which Benjamin calls progress, irresistibly into the future.[4]

Zoe Leonard: Display is on view at Maxwell Graham from September 3 through October 25, 2025.

[1] In an Interview Magazine feature from February of this year, the singer and actor Selena Gomez was portrayed in a Dior bodysuit alongside producer and songwriter Benny Blanco, her husband, who wore a full-body suit of armor, the helmet cocked under his right arm in Mel Ottenberg, “Benny and Selena Against the World,” Interview, February 14, 2025. Photograph by Roe Ethridge.

[2] Antonio Gramsci, Selections from Cultural Writings, ed. David Forgacs and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, trans. William Boelhower (Harvard University Press, 1985), 250–51.

[3] Michael Warner, Publics and Counterpublics (Zone Books: 2002).

[4] Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (Schocken Books, 1968), 257–258.