TO HELL WITH THE GANDER: Interview with Elbert Joseph Perez

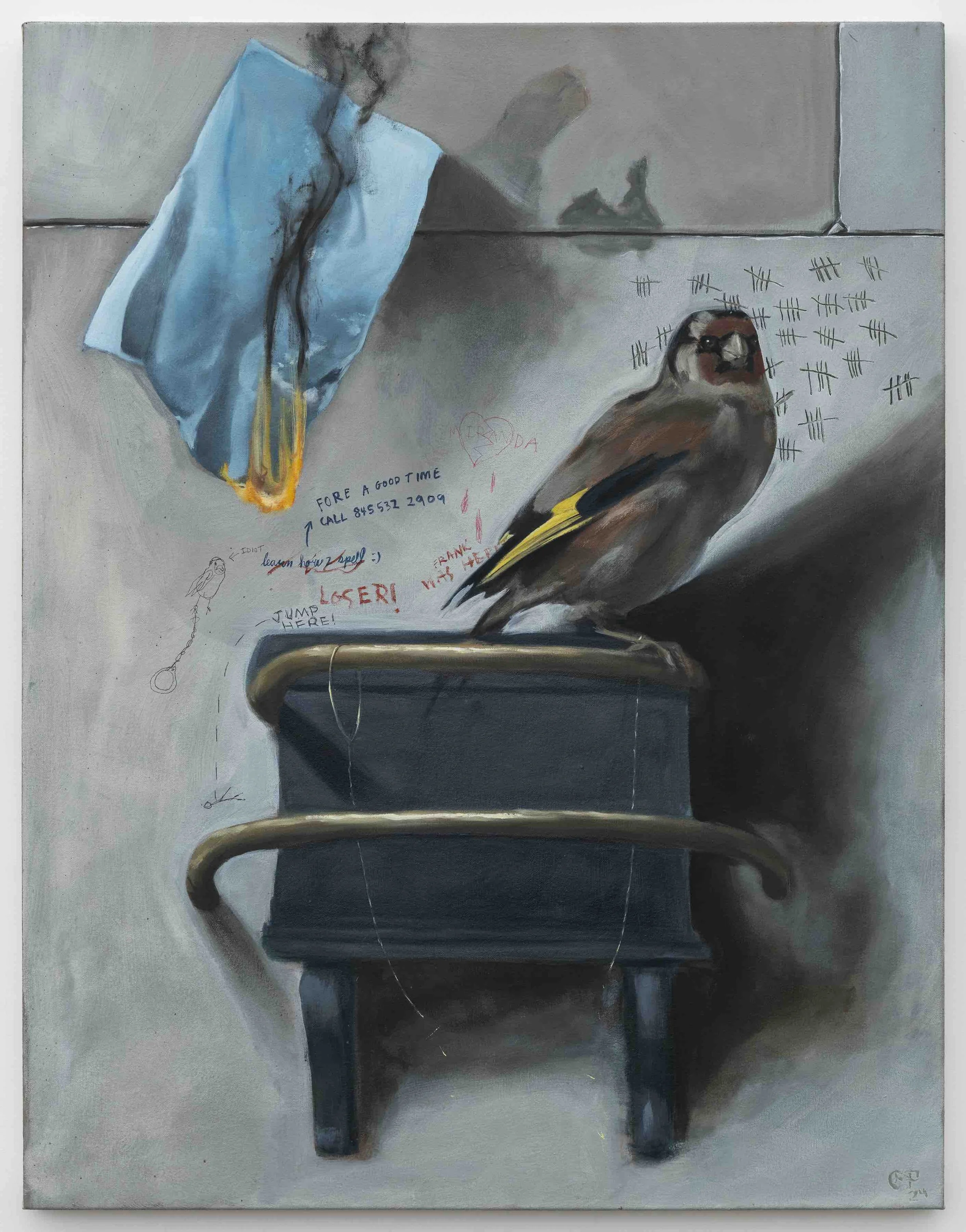

In TO HELL WITH THE GANDER, which opened at Chozick Family Art Gallery on September 2, Elbert Joseph Perez advances a practice that moves between allegory and absurdity by staging human contradictions through animals and ornamental detritus. Painted in oil and undercut with the artist’s corrosive humor, swans, ducks, cows, butterflies, and porcelain figurines stand in for human and societal folly and expose its manifestations of grief, anger, toxicity, and accelerating political disillusionment.

Throughout this interview, Perez reflects on his trajectory as a self-taught painter informed by the diagnostic problem-solving that takes place while working in his father’s auto garage, his engagement with Alain Badiou’s Metapolitics as a framework for critiquing self-indulgent political agendas, and his investment in utilising allegories as an incisive strategy for portraying shortsightedness. By addressing the instability of belief and fragility of emotions, his newest body of paintings functions as both confrontational and satirical reflections of the dysfunctional and crumbling ideological scaffoldings of contemporary life.

Clare Gemima: How did you settle on the title for your show? It made me laugh at first. Since your work often channels human failures and fragility through animal imagery, does TO HELL WITH THE GANDER act as a sly dismissal of the masculine—whether man, god, hyper-masculinity, or broader systems of power?

Elbert Joseph Perez: I had actually taken it from its idiomatic use, a proverbial rule—if it works for me, it should work for someone else. In these works in particular, I channelled an attitude closer to the title after having failed conversations with various people. Throughout my attempts to find some middle ground, it became clear that ideologies have become so rigid that it feels impossible at times to expect a productive combination of differing thoughts. The title became a proclamation of the immediate dismissal of the “other.” It can be readily applied to some of the smaller or larger systems you mentioned, but it is ultimately a cheeky way of pointing out a resignation of the ego. I don’t really care who else this works for, as long as it works for me.

CG: You’re a self-taught painter, and your practice has grown in tandem with your work as an auto mechanic in your father’s garage. What does “self-taught” really mean to you, and how do these two worlds of yours bleed into each other?

EJP: I guess self-taught means taking the initiative to find the resources you need to learn something without institutional guidance. Admittedly, it’s difficult to consider myself an autodidact, considering I didn’t really teach myself anything. I was guided by different sources, materials, friends, and artists who were gracious enough to answer my questions along the way. My father grew up in a similar setting in his trade, being resourceful and mindful with his work. He never finished formal education, so something he taught me was that if you wanted to know something, you had to go and figure it out yourself. You had to put your hands on it. Granted, working with him is more akin to a mentorship. There are still moments in the garage where problems arise that neither one of us has run into before, where we have to start doing research to diagnose issues. He and my brother test me often. The garage is a place where simple things can become complicated, and dialectics become diagnostic tools. I feel like these moments apply not only when I am in the studio, but to life in general. There's a solution to any problem, and asking the right questions will illuminate a decent avenue towards one.

CG: While making this show, you looked into Alain Badiou’s book Metapolitics, first published in 1998. Some of the main ideas he proposes are that politics should be understood as a process of producing truth, and that political reality is separate from public opinion. He also critiques the forces of individual interests behind liberalism. What aspect of his philosophies resonated with you the most as you developed your new paintings, and do you view works, such as Homeland Security and Neighborhood Watch (Check Out My Badge), for example, as interventions into current political discourse?

EJP: I recently started reading Metapolitics in an attempt to quietly diagnose the pitfalls of political discourse and to learn more about infrastructural failures. I am a big believer in Badiou’s notion that opinion drives political orientation, and that truth and equality in a political setting are largely debased by subscription to prepackaged ethical or parliamentary tenets, which are so often just designations of self-interest. I think that by acknowledging political opinion as an extension of self-preservation, we could (idealistically) begin to imagine a form of liberty that functions not for one group of individuals, but as something so generic and functional that it remains untouched by tribalism. Like marriage solely being a state-recognized union of two individuals, for example, or that any form of labor should allow an individual to live comfortably. We really have people out here believing that if you work in fast food, you aren’t able to expect to afford rent. In saying this, my works aren’t so much positive interventions in these beliefs as they are confrontational reflections, or ways of asking viewers to look at what emerges when we fail to acknowledge our own shortsightedness. Politics is personal, and vice versa. Indulging in this as part of my process has changed my belief system and forced me to consider the consequences of my actions. I’m thinking about the gander.

CG: Extremely cute animals recur throughout this show and in your paintings overall: geese, ducks, cows, butterflies, even chrysalises. You’ve described them as stand-ins for human contradictions, biases, and instincts. Can you talk about the decision to stage human drama through animal surrogates? I also know your studio is in the Catskills, and I wonder if any of your imagery is sourced from real-life run-ins with these sorts of creatures.

EJP: I have always felt that it’s odd to use humans as subjects to comment on humanity. It’s less fun to replicate their baser instincts and behavior. Allegories are more fun to witness and decipher, and when one investigates something beautifully abstract on a deeper level, they will always walk away with something. People love stories. I love stories. Historically, many cultures have attributed qualities of themselves to animals, and for me to recontextualize them to fit certain pedigrees of human behavior in a more contemporary sense feels no different. Swans I love in particular, because they have always been a symbol of grace, but what goes ignored is their proclivities for violence. There was a swan that drowned a man in 2012. I think I’m just committing to an old practice and trying to be a little more honest about it. Being in the Catskills, I have had the fortune of meeting every animal I have painted so far. I think I have some of their numbers still saved in my phone!

CG: On a more personal note, have you found yourself working through heartbreak, loss, or forms of disillusionment while making this series of paintings?

EJP: I’ve definitely dealt with a lot throughout working on this series, and I wouldn’t be human if I wasn’t touched by affliction. I went through a difficult heartbreak earlier in the year, lost a few friends, and definitely have wondered what my role as an American is. The concept of suffering is one that I turn to often because it’s such a relevant plight. The universality of suffering allows even the most ideologically rigid to lend a hand or an ear, if they have some empathy at least. I often bring these woes to the table because they are things we can all recognize. It’s the same with humor. We all recognize a stranger laughing as much as a stranger weeping. By exposing my suffering and incorporating a touch of humor, my work becomes slightly more palatable, while hopefully also being deeply relatable. To think about the heartbreak, loss, fear, and even political disillusionment that I’ve experienced while making these works . . . it would truly send me over the moon if a viewer could look at a painting and relate to it in some way.

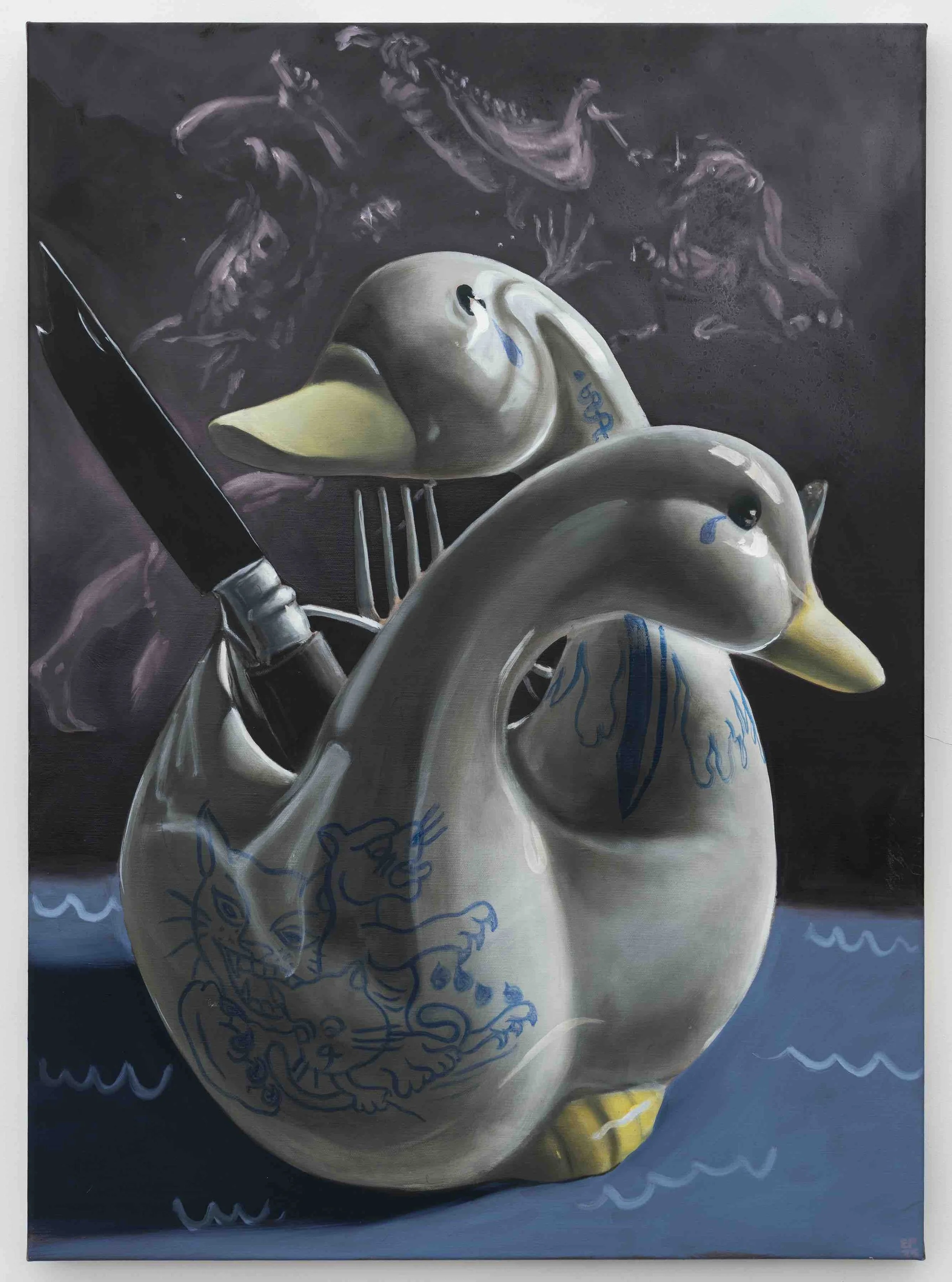

CG: In Can and Able, two glossy porcelain ducks streaked with tears double as vessels for cutlery. Instead of retelling the story of Cain and Abel—the first brothers born to Adam and Eve, whose rivalry ended in murder—you reincarnate them as banal, ornamental household décor. The painting collapses that cycle of violent jealousy into something absurd but fragile. What are you critiquing through the use of larger narratives like this, and what draws you to working with them as part of your conceptual framework?

EJP: I hope I’m pointing out how absurd and fragile feelings like anger are! I grew up in a home where anger was almost the only means of communication. Anger is an overutilized yet misunderstood emotion, and it seems to be the one that is driving the general social narrative today. There are different versions of anger, but the one I hope to highlight is the tempestuous anger of ignorance. It is so easy, almost so commonplace, to react without temperance. There are so many things to be angry about in this world, don’t get me wrong, but how that emotion is carried from one place to another has justified some of the worst behavior I have seen, and at times even perpetrated myself. I’m hoping to make an appeal to our sense of emotions, trying to say, “You can be mad, but see where it might take you when you use it inappropriately.” I think about how delicate and fragile our emotions really are. I used to be someone full of indiscriminate rage, and I know how much it used to hurt everyone, myself included.

CG: In past writing, I’ve described your humor as “getting darker by the minute.” In this exhibition, destruction, death, and short-sightedness keep surfacing, whether through the butterfly in Thinking About My Future that proudly leads a Monsanto's flag in flutter, or a harlequin clown dangling a carrot before the world in I Giveth and Taketh Awayeth. Do you see these works as symptomatic of the current political climate—the precariousness of war, nationalism, ideological purity, and/or dangerous agricultural expansion?

EJP: You’re not wrong! Our politics have been shaped slowly by more perverse and selfish forms of thinking that have given way to powerful individuals with similar feelings, feigned or not, and allowed them to capitalize on them. I even see it in the church. I grew up in a religious household, and my parents are still active members of their Baptist congregation. Hearing a lot of them talk about politics, which used to be fairly rare, has become beyond disheartening. Contemporary “politics” have melded with institutions in a way that is, honestly, to me, disgusting. There are some ideological tenets that can happily be thrown in the trash if it means the power of an institution achieves a greater reach. But these institutions and groups are just appealing to their base sense of selves, veiled in tattered versions of their beliefs. There will always be people who solely have their own interests at heart and are willing to forgo or reinterpret their beliefs to serve only a version of themselves. I think this is a cycle that won’t ever stop, and one that will always try to dominate others if we don’t figure out how to compartmentalize values. I am just responding to the climate.

Lately, I have been noticing a lot of beauty outside of the really hard moments though, so I think I’ll find some reasons to get a little less dark soon.

Elbert Joseph Perez: TO HELL WITH THE GANDER is on view at Chozick Family Gallery from September 2 to 27, 2025. The exhibition will be accompanied by the artist’s debut monograph, Barking at the Moon, published by FAMILY BOOKS with texts by Julia Weist and Annie Bielski.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.