Reclaiming Distorted Archetypes: THE BOYS CLUB (Redacted)

How can Pop Art, an artistic endeavor developed to critique mainstream consumerism, define itself in a society where there is no real mainstream to oppose? With data mining and social media feeding on an endless feedback loop of self-reifying labels and micro-labels, where every individual can seamlessly don any multitude of cores, be anything -coded, and giving everything, where does the argument for individuality fit? Do artworks that address this anxiety provide hope or sound a droll death knell? Curator Cortney Connolly proposes that they provide, to begin with, awareness: awareness not as a step to creating the next niche to situate oneself, but as a solution on its own. THE BOYS CLUB, curated by Cortney Connolly, is on view at Susan Inglett Gallery until January 25th, offering a deceptively compact survey of contemporary challenges to the Pop Art methodology. Showcasing several artists of diverse backgrounds, Connolly aims to combat the de-contextualization of images and symbols in mass media through an assemblage of artists whose work deliberately eschews legibility.

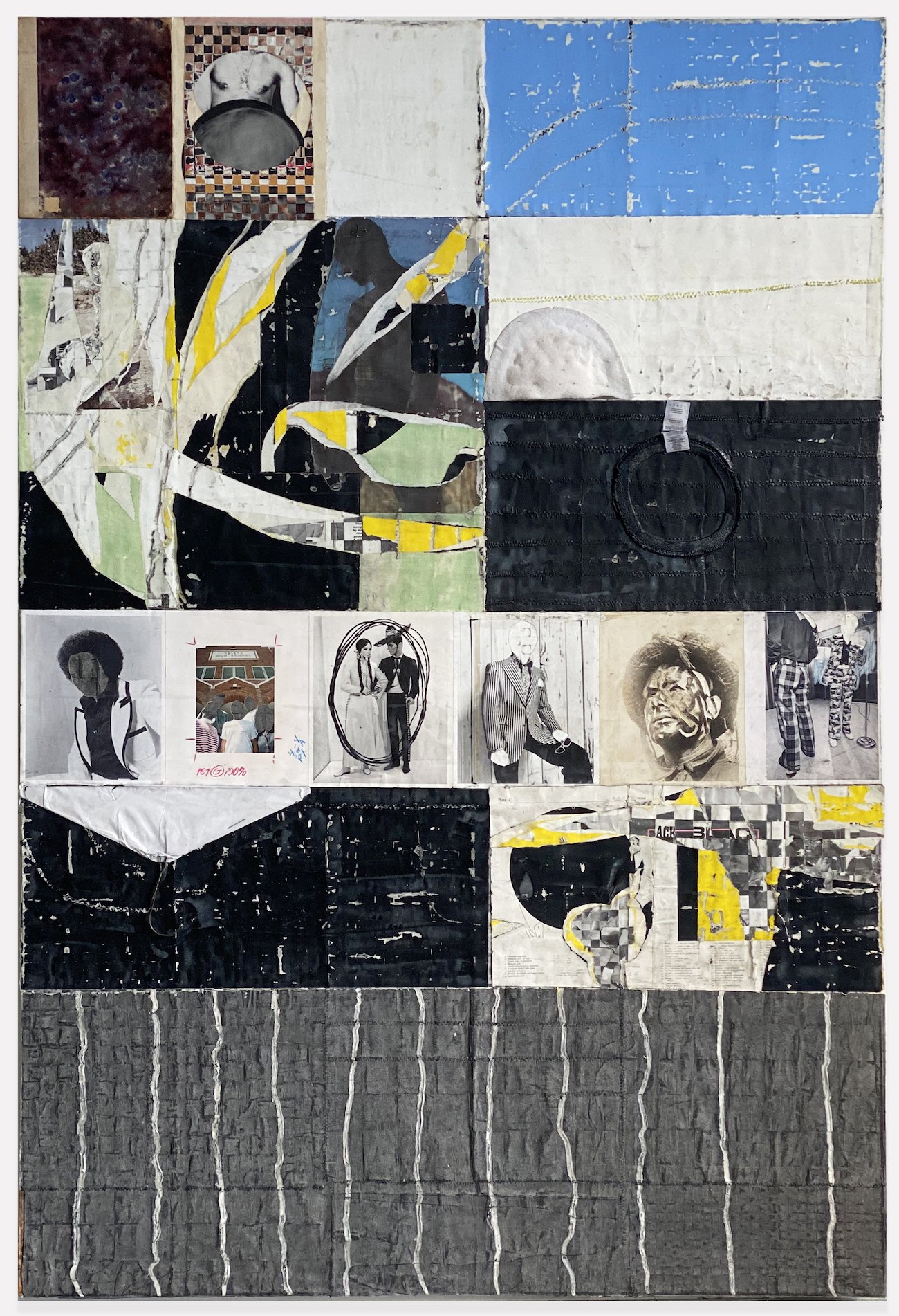

Together, these works seek to reclaim the distorted bodies and symbols of mass marketing, replacing universal signifiers with “hyper-intentional” images, each with its own uncanny texture and aura. Among the most immediately striking examples is Troy Montes Michie’s Phases (2020), whose riotous assortment of textile and printed materials defy their grid framework through jutting shoulder pads and shredded magazine scraps. A swirl of ripping, tearing, weaving, and pulling produces a delicate but intensely historical quilt of printed images, textile souvenirs, and textual scraps, exemplifying the deeply contextualized visual histories that govern the show. Nina Hartmann’s Mind Control Image Connectivity (Maze B) (2024), an eerily industrial plastic block of research-based photo collage, is contained by movable metal barriers on grooved tracks inspired by the maze-like enclosures used in behavioral tests with animals. Refusing to offer a streamlined visual message, Hartmann’s work asks the viewer to interrogate its meaning through accompanying contextual information rather than on formalism alone. All the artists represented in THE BOYS CLUB unearth how mass media’s dissolution of the cultural mainstream renders meaningless the signals of previously distinct signifiers.

None of these works are legible at one glance. They each require deep engagement at multiple levels to reach an understanding of their critical messages. Through the act of digging, of climbing into each separate space and attempting to experience it fully, these artists prompt true attention paid to their methods. In this, they are perfectly in tune with the original aims of the first Pop Art movement, as Connolly deftly articulates through the placement of one historic artist—Erica Rutherford, one of the first openly transgender women artists and a prominent contemporary of the first British Pop Artists. Slightly hidden but aptly anchoring the show’s more contemporary works, Rutherford’s The Startled Model (1977), a small framed print on the gallery’s rear wall, provides a reminder of the aesthetic theories that first defined the Pop Artist movement, attempting to literally deconstruct and lay bare the mechanisms of mass print media in twentieth-century consumerism.

Rutherford’s print hangs directly opposite the loudest work in this show: Natalie Ochoa’s I Love Mount Rushmore (2024), a padded box containing an embellished print of Mount Rushmore accompanied by a small box speaker with a tantalizing red button. When the button is pushed, the speaker shrieks out a TikTok audio that, for this Gen Z art historian, made the work, indeed the entire show, as immediately legible as a billboard: a layering of audio including eagle screeches and the voice of Kevin James yelling “God bless our troops, God bless America, and gentleman, START! YOUR! ENGINES!” The clip’s unmistakable satire underlines the tackiness and hypocrisy of the Mount Rushmore photograph (a monument carved into sacred Indigenous land), heightened by Ochoa’s trademark embroidery work mimicking such quaint images of Americana as a hot dog spreading a picnic blanket. The speaker’s inclusion effectively brackets the show, parodying the explanatory spoon-feeding of analytical content that Pop Art subverts.

Pop Art of the 1960s was not conceived specifically for the consumption of mass audiences, yet its use of widely available advertising imagery allowed it to be universally readable to an audience far bigger than the educated elite who developed its modernist principles. In THE BOYS CLUB, Pop Art challenges itself to be less legible, to become hyper-specific, and to demand once more a contextual gaze. A single glance and a double-tap are not enough to grasp the messaging in these works; one must devote time and mental energy to engaging with their contextual meaning, questioning and researching, and, maybe most importantly, discussing. With awareness as a goal, Pop Art retreats from a mass-market voyeur and asks to be looked at rather than seen, read instead of received.

THE BOYS CLUB, curated by Cortney Connolly, is on view at Susan Inglett Gallery until January 25, 2025.

Edited by Xuezhu Jenny Wang