On Exchange with Maren Hassinger and Senga Nengudi

Maren Hassinger and Senga Nengudi first met in Los Angeles in the late 1970s, young, restless, and still finding their footing amid a Black avant-garde that slipped fluidly between performance, sculpture, film, and dance. Hassinger’s work grew out of movement, folding sound, touch, and the marrying of industrial and organic materials into sculpture. Meanwhile, Nengudi’s practice turned toward ritual, elasticity, and the everyday, most famously in her R.S.V.P. works, where stretched pantyhose hold the body’s strain. Working as Black women artists in a period when institutional support was scarce, their practices took shape through mutual exchange. What bound the two artists were their phone calls, during which one idea sparked the next, fostering a rhythm of looking, listening, and replying that kept their work alive and in motion.

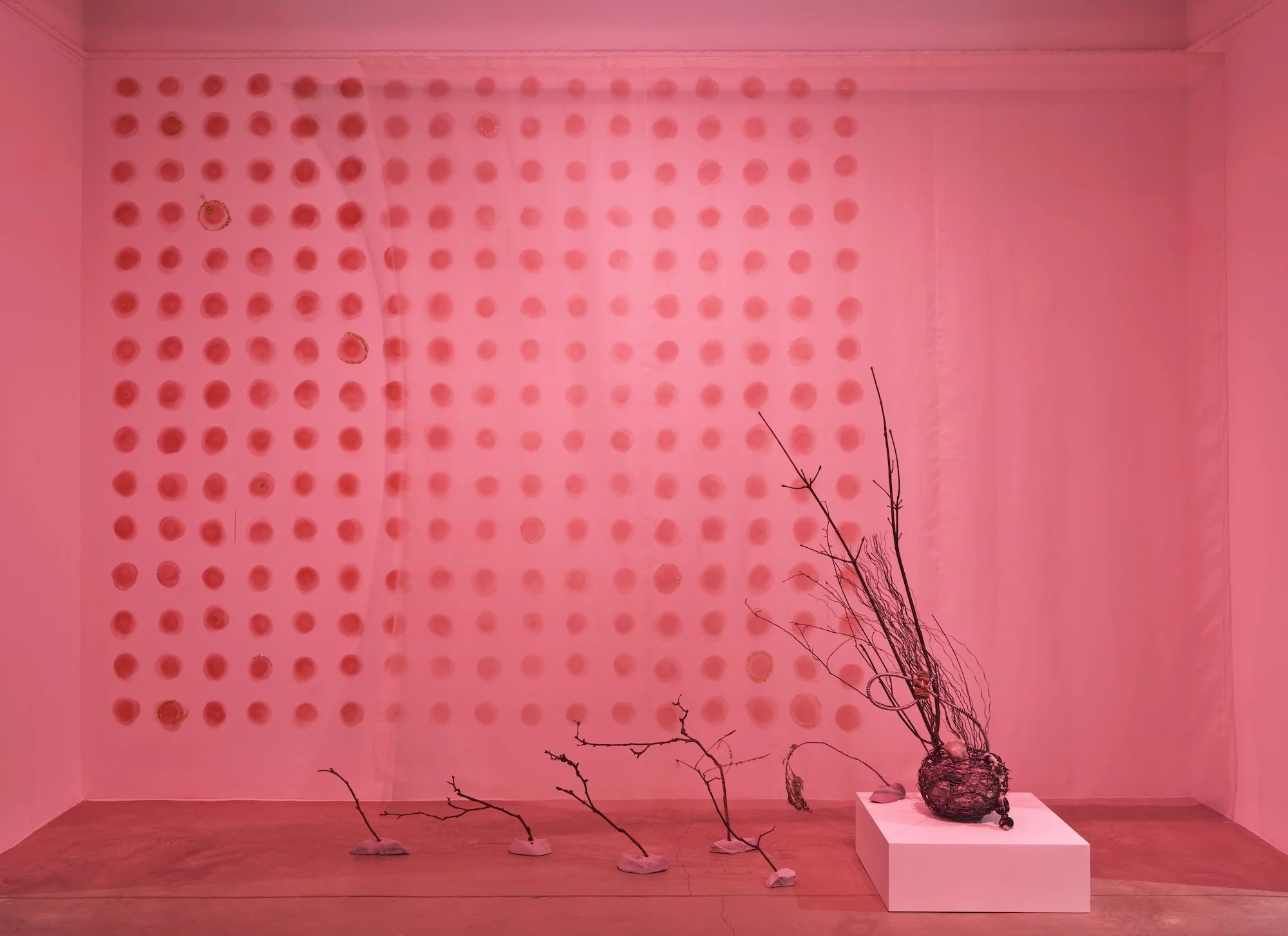

On view at the Columbus Museum of Art through January 11, 2026, Las Vegas Ikebana, the first museum retrospective devoted to their collaborative practice, traces this back-and-forth across decades. The exhibition’s title was coined by the artists in 2000, drawing on Hassinger’s time working as a florist in Los Angeles and Nengudi’s engagement with Japanese aesthetics. Since then, it has served as a touchstone for the shared language the two artists return to again and again, a framework through which the latent poetics that powered their individual and joint practices now come into view. Many of the works are presented publicly for the first time, including Video Letters (1998), Senga’s House (2003), Doorway Yoga (2003), Conversation (2005), Gravel Dance (2005), and House Dances (2007), all of which emerged from a series of informal residencies in which each artist hosted the other in their home.

Sahir Ahmed: When you think back on your earliest collaborations, what stands out?

Senga Nengudi: It was always a back and forth of, “Why don’t we do this? Why don't we do that?” We were excited. There was myself and Maren, but also Ulysses Jenkins, Franklin Parker, and Houston Conwill, who were partners of ours. We would all somewhat work together to create newness.

Maren Hassinger: Yes, we were all friends. I remember the times when we’d talk on the phone and the kids would be making so much noise in the background, becoming part of the landscape of our conversations. Those were fun times. Even if we couldn’t always have a full conversation, family running around reminded us that we were both artists and parents, and that reality became part of the work. To have a conversation with somebody who's truly interested is not like having a conversation with somebody who’s like, “Oh yeah, that's nice.”

SN: She would always follow through on whatever we talked about.

MH: Right. It wasn't like we had the same mindset about what art should be, but we were intellectually invested in one another's actions, at a time when there weren't a lot of people screaming for our work. These really long drawn-out phone conversations were actually the impulse for She Said (2025).

SN: A lot of that piece has to do with how we were feeling about the art world, politics, and other elements that we talked about to keep us going. We wanted to keep the ideas flowing, so came the idea of the ticker tape.

We imagined that as people look up at it they’d see a segment, a snippet of information, but never the whole idea. In general, it stems from this idea that it’s hard to function alone in the world, period.

MH: Agreed. The artist’s process is often singular. You’re in your studio and you’re focused. So when you collaborate with others, it opens you up.

SN: I thought once, maybe it’s like an affair. That moment of excitement and exploration, then you go home and life is normal, but some of the stuff from that time stays with you.

MH: I don’t know about the affair thing. But yes, when you have someone to talk to, ideas happen. Like people in an office bouncing things around. We worked on similar issues, with the same desire to say something important or necessary. And it was fun. Not negative, never imitative. It also provided immediate feedback. You’re not looking at something you made for weeks asking yourself, “Is this good?” Someone is there with you that can say, “Well, it could be better.” That was always convenient.

SA: Do you feel the collaboration affected either of your individual practices in any negative way?

MH: No, not at all. I think that’s why the “affair” metaphor maybe doesn’t quite work for me. We always maintained our own practices. And when we came together, we were able to set that aside and do something different. That was really the point. I think our similarities happened almost by osmosis. It wasn’t a conscious decision but was more that each other’s way of doing things slowly folded into how we approached ideas. But I can’t point to anything specific, because the integrity of our individual processes stayed intact. That was important to both of us.

SN: In some ways, the collaborations became a different kind of practice altogether. What we really did was talk. We talked on the phone constantly, about ideas, about life. We moved around a lot too. There was a lot of physical movement, not just conceptual exchange.

MH: I don’t even know how much of our conversations were strictly about work.

SN: I think it was all blended together. We talked, but we also took what we used to call “field trips.” We’d find ourselves in different, unexpected places, and those locations mattered. The site itself would suggest certain activities, and then we’d bring our ideas into that context and try things out. The location was never neutral.

MH: And it was freeing. I never felt that anything was being compromised. I didn’t feel like my work was changing in a way that felt uncomfortable. It was more about the relationship itself.

SA: Location seems especially important in this exhibition, particularly given the title Las Vegas Ikebana. Can you talk about that?

MH: The term really solidified as an ongoing project around the year 2000. Las Vegas is supposed to be a metaphor for this playground of gambling, stage shows, and American spectacle. But there’s another side to it: addiction, desperation, people caught in cycles they can’t escape. Las Vegas actually gives me the creeps. My mother moved there at one point in her life, when she had a boyfriend who was a gambler. That experience really stayed with me.

SN: We were really thinking about opposites—Ikebana being this symbol of balance, grace, and simplicity, versus the crassness of Las Vegas as the capital of glitter, excess, and greed. It pulls people in.

MH: At the same time, I had worked in a flower store so that language was already part of my life.

SN: Around then, we were also working on a project where we mailed artwork back and forth to each other. We were both going through extremely personal situations, and the exchange became a way to stay connected, to keep our commitment to art and to our practices. We would send something every month, sometimes more often—drawings, images, ideas. Postcards from Las Vegas started entering the mix; I remember a photo of Diddy and J.Lo in that infamous dress. All of this cultural debris began floating between us.

MH: Some of those postcards were made while I was visiting my mother in Las Vegas in the late ’90s. Ritual was also important. The ritual of trying to work every day. Sitting down, standing up, just trying to do something, anything, other than scream at your children or make dinner. We knew what was happening in each other’s lives. We talked about ideas, made promises to do things, and shared what we’d made. Without that, it’s very easy to get lost in housekeeping.

SN: There’s ritual on a daily level—washing dishes, planning meals—but there’s also ritual on a spiritual level. If you want a certain result, you combine elements in a particular way. That process can create something euphoric. For me, ritual has always been about bringing energies together. In Freeway Fets (1978), for example, I was trying to create a coming-together of male and female energies that felt fractured at the time. I positioned myself in the middle, working with Maren and David Hammons to try to create a better relationship, something more balanced.

MH: It keeps you going.

We used to ask each other, “Are you going to do something this year?” And if one of us had an exhibition, it would be so exciting.

SN: Things were very different then. Now there are many shows, galleries sending our work out into the world. That part isn’t our primary concern anymore. But at the beginning, the question was always: How do we get this work out? How do we share what we’re feeling? How do we make people interested? It took a long time.

MH: The most important ritual was sticking with it.

SN: Yes. And witnessing ourselves, and each other, at different moments.

SA: If your collaboration were an Ikebana arrangement, what would it contain?

MH: I imagine a flower arrangement in a pond, glitter floating on the surface, wires jutting out in different directions, very fragrant flowers, and a lily pad resting on top.

SN: That sounds about right.

Maren Hassinger and Senga Nengudi: Las Vegas Ikebana is on view through January 11, 2026 at the Columbus Museum of Art.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.