NOTHING WAS EVER THE SAME AGAIN

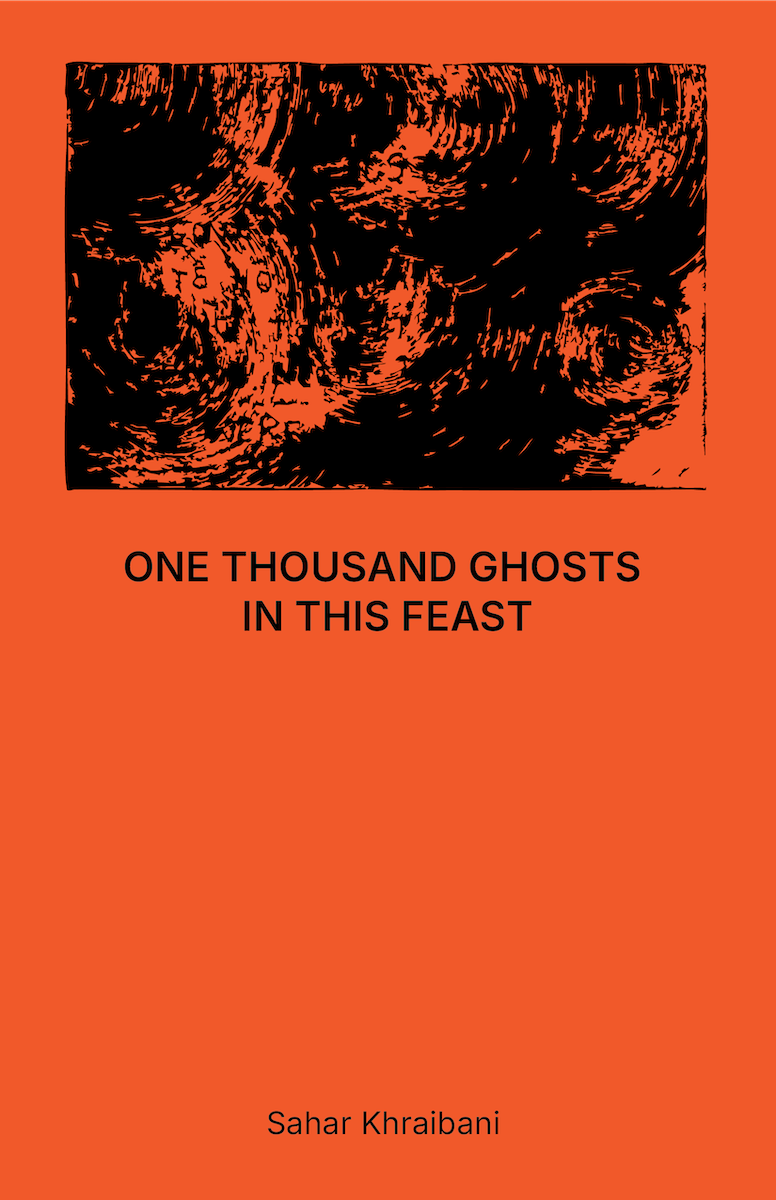

Sahar Khraibani’s ONE THOUSAND GHOSTS IN THIS FEAST contends with desire, grief, and language as sites of injury and release. Written over a period of three days when Khraibani was a resident at MacDowell—amid ongoing genocide, land seizure, and displacement—the long poem’s all-caps, first-person address impels the poem forward, centering intertextuality as a force through which spectral presences shine. In an interview with Alex Schmidt, Khraibani discusses their malleable modes of making across visual, textual, and time-based practices.

Alex Schmidt: How you write is so visual. Your use of truncated stanzas with caps lock, especially, reminds me of Juliana Huxtable’s Mucus in my Pineal Gland or Nate Pritchard’s The Matrix Poems: 1960–1970, as well as protest posters, Jenny Holzer’s aphorisms, etc. How does the use of the caps lock work for you, as a visually attuned writer?

Sahar Khraibani: I love how visual poetry can get. There’s a lot of flexibility in the way you go about presenting words. Sometimes this leads to a change of intonation or a visual expression that accompanies the words. I really like that you bring up N. H. Pritchard because he is a big influence for me, as well as Juliana Huxtable’s work and many other poets who utilize visual language in service of poetry. All caps was intuitively important for ONE THOUSAND GHOSTS IN THIS FEAST because it came out of me in the form of a ghostly scream. It felt particularly pertinent to the urgency of the text.

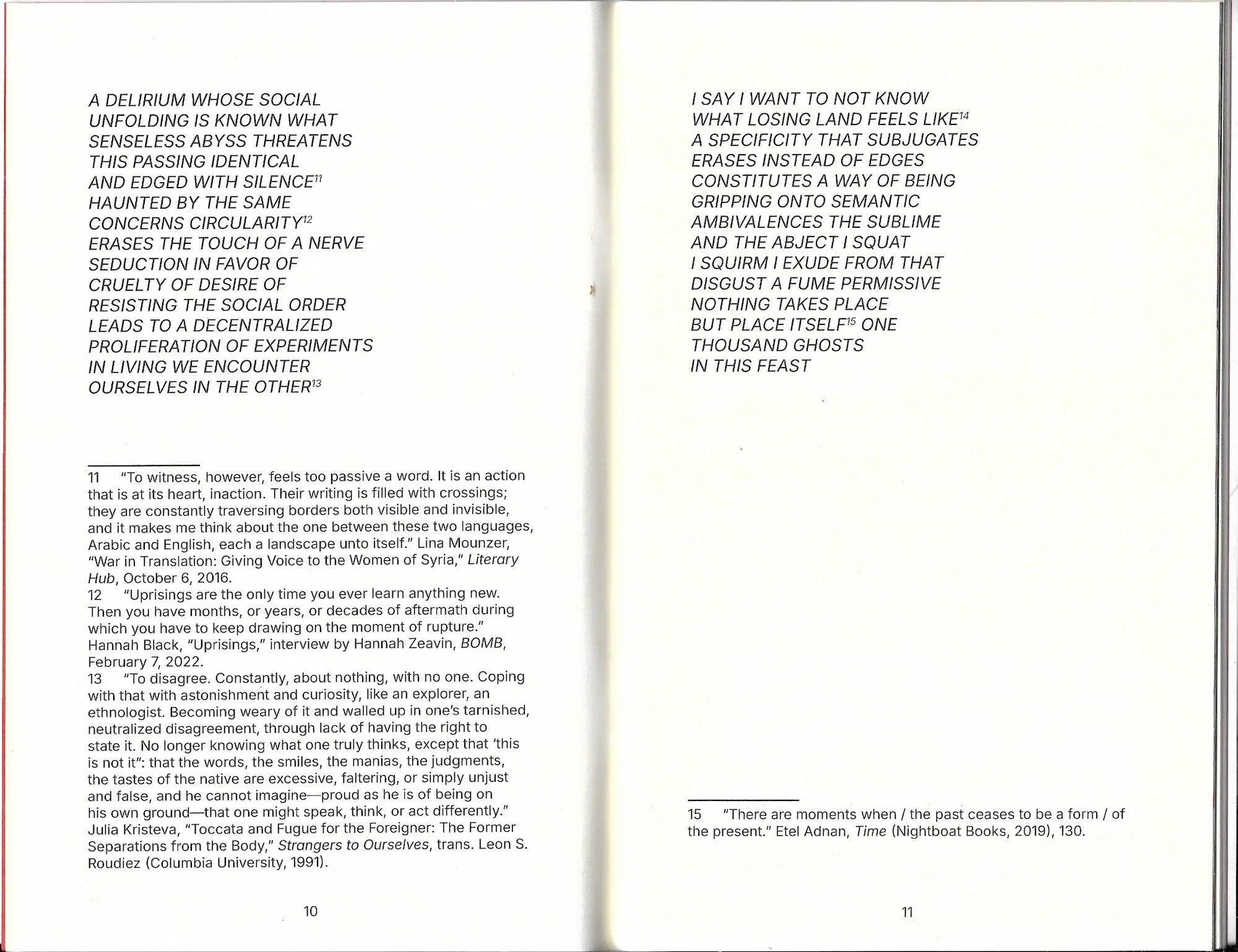

AS: The first half of ONE THOUSAND GHOSTS IN THIS FEAST is glutted with citations. Sometimes the citations seem to expand/expound upon the potentiality of a word. Sometimes they seem to credit. Sometimes they are references inward or outward. Can you explain more about your citation process? Did you cite as you wrote? Or did you cite as you were able to name the “ghosts” of your text later on?

SK: The citations in ONE THOUSAND GHOSTS IN THIS FEAST are the literal guts of the book. They are everything that I was reading, thinking about, and looking at in the period leading up to the writing. I usually spend long periods of time just gathering a web of influences before I can write, and I often wonder what other writers are reading when they’re writing, especially poetry. I wanted to be very generous with my reading list, especially since I reference a lot of books and works that aren't on mainstream reading lists (namely, not very Western, not very white, etc.). It felt very important for the footnotes to have their own life, not to necessarily “cite” per se, but to explain where a certain concept, idea, or stanza came from, even when it’s not an immediate extraction or citation. I think it was Fred Moten who says that we all write together, because we’re all in each other’s work, whether consciously or subconsciously. I wanted to bring all these writers, thinkers, makers, and poets to the table with me. I was in conversation with them, and I hope the reader also gets inspired to check out their work or to go on their own tangents.

AS: I wonder especially about this citation: “Traversing borders both visible and invisible, and it makes me think about the one between these two languages, Arabic and English, each a landscape unto itself” (Lina Mounzer). On the next page, you say: “NOTHING TAKES PLACE BUT PLACE ITSELF.” Is language a landscape?

SK: I love this question! Is language a landscape? In many ways, yes, and in many ways no. To me, language is a place; it is a geography. We can use it, erase it, and butcher it. We can preserve it. It is often a point of access, and many times it can be a barrier. Language is the first tool of colonialism. When empires rule over lands, they try to impose their own language. I once saw this statistic that 60% of languages spoken worldwide in 1795 are now extinct. That is a massive amount.

AS: Before you wrote the text, you shared that you “could not stomach having any language.” Is citation—also known as ancestors, community, intellectual family—a vehicle for stomaching?

SK: Absolutely. I think writers were really struggling over the past few years to “find language” to express all the atrocities we’ve been experiencing.

AS: You wrote ONE THOUSAND GHOSTS IN THIS FEAST in what you call a “three-day possession” at MacDowell, having “decompressed like an inflated pool” upon your arrival. This is a strong visual for me. How did this decompression translate to the drawing and printmaking practice?

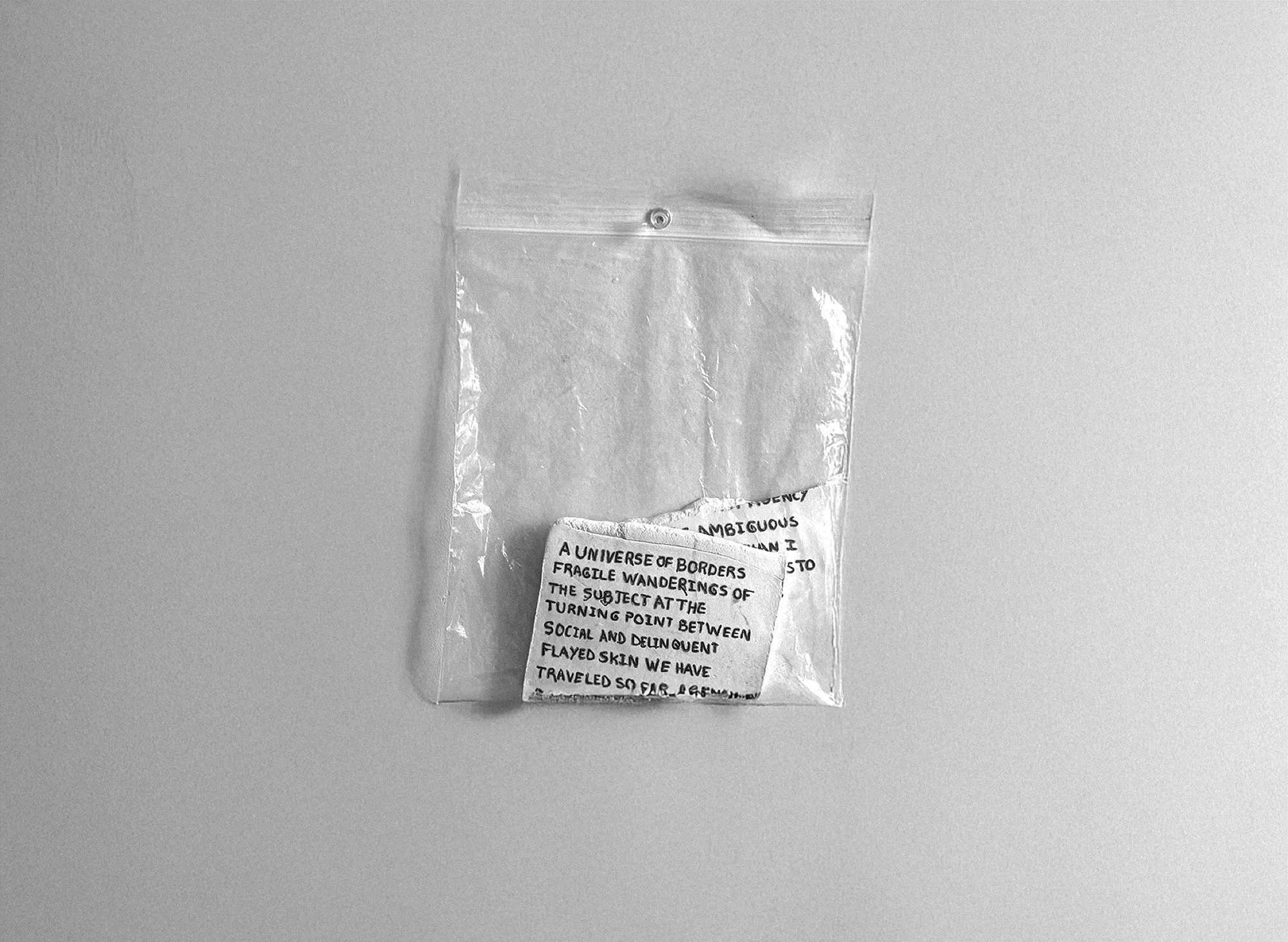

SK: That is correct! I wrote this text over the span of three days, in what I am sure was a ghostly possession. Interestingly enough, the way this text started was completely visual. Another fellow at MacDowell had given me some air-dry clay the day before to experiment with, and I made these rounded rectangles, which I then engraved. The first thing I engraved was THERE ARE ONE THOUSAND GHOSTS IN THIS FEAST. And from then, I engraved a couple more stanzas, and immediately, it all poured out of me, and I had to move to my notebook. The poem is 48 pages long because my notebook had only 48 pages, and I decided it was the perfect length for a book-length poem. So, I guess, to answer your question, the decompression was actually me stepping away from the screen and working with my hands in an embodied way, which led me back to writing.

AS: You usually design the artwork for your publications. Can you explain the relationship between drawing and poetry? Is there one?

SK: To me, drawing and poetry are interconnected. One cannot exist without the other in my practice. I write everything by hand, and then I move to the screen. But this practice of writing by hand often leads me to drawing. Whenever I am working on a text, I am usually working on some kind of visual alongside it. Not because it’s part of the brief or the request, but because it’s intuitive to me. I flesh out ideas and language better when I am also visualizing them. I have had a long career as a designer and printmaker, and I’ve worked particularly with etching and engraving. The process is so laborious in its necessity for gentleness. It’s this balance that you have to strike between digging deeper and also not ruining a plate. I think this is a perfect metaphor for my poetry writing and my drawing practice.

AS: “FACE PLUNGED INTO SOIL / THERE ARE THOUSANDS OF GHOSTS UNDER MY FEET.” This stanza summons Ana Mendieta for me. Which, if any, visual artists inspire your writing?

SK: Ana Mendieta is a huge inspiration for me. Her work touches me every time, and each time I revisit it, I uncover more layers. I’m so glad that this stanza evoked Mendieta for you, because it feels so unconscious to me yet so accurate. I am also deeply inspired and moved by Etel Adnan; her entire body of work feels like a blueprint for me: someone who works across mediums, with no labels or harsh delineations. For more contemporary references, I am a big fan of Meriem Bennani, Walid Raad, Michael Rakowitz, and Renee Gladman. I think they all use language in these fascinating ways that make it into a character in their work. I feel very lucky to have many artists who are also friends, and I am so moved and inspired by their work and creative energy.

AS: “THE WAR ON THE SCREEN / IT ALL STARTED WITH A DRAWING / SOMEONE SOMEWHERE PUT / PEN TO PAPER AND NOTHING WAS EVER THE SAME AGAIN.” Talk to me about this dystopic mark—the original sin.

SK: This one feels very charged for me, a moment of true anger. To think of the troubles we face in our world today, how they are all essentially about borders, who’s crossing them and why, and who gets the right to. Then, when you zoom out for a second, you realize that these are just imaginary lines, demarcations that were created by Empires with a capital E. They are tearing everything apart. I went to a French school in Beirut, which was under the French Mandate for a long time, and I learned everything about French history and geography before I ever learned anything about my own place of origin. I remember being particularly struck by the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which is exactly what I was referring to in this stanza: some politicians met and divided parts of the world among different empires (the French, British, etc.). It was just a moment, and then nothing was ever the same again.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Sahar Khraibani is a writer and artist whose work has been presented with Montez Press, The Brooklyn Rail, Magnum Foundation, the Poetry Foundation, the Poetry Project, and Hyperallergic, among others. Sahar is a recipient of the Creative Capital / Arts Writers Grant, a fellowship at The Poetry Project, a MacDowell Fellowship, a 2024 residency at Mass MoCA, and is an alumnus of the Whitney Independent Study Program. Sahar teaches at Pratt Institute and is the author of Anatomy of A Refusal (1080PRESS, 2025) and ONE THOUSAND GHOSTS IN THIS FEAST (Wendy’s Subway, 2025).