Shared Sand and Soul: In Conversation with Ismail Ferdous

Ismail Ferdous’s photographic series Sea Beach resists the tourist gaze, offering a body of work that is emotionally attuned, culturally rooted, and quietly radical. Through intimate portraits of life along Cox’s Bazar, he invites viewers to witness the beach not as a vacation destination, but as a site of personal and collective meaning shaped by migration, cultural expression, and joy.

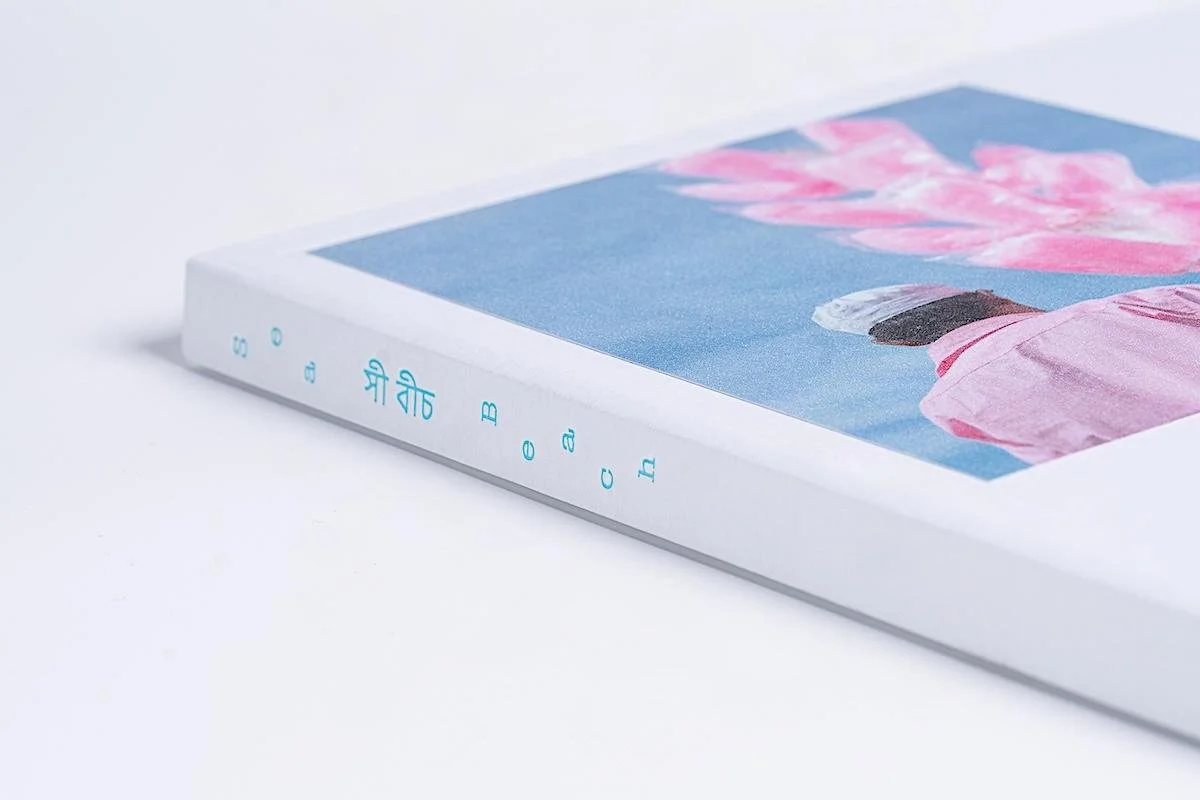

Ferdous’s photographs explore how people carry themselves in public space, celebrate, connect, and rest. His visual language holds space for cultural rhythm, generational memory, and everyday aspiration. In his hands, the beach becomes a living character: one that personifies Bangladeshi utopia. Through these questions, we seek to uncover the unspoken ethics behind the lens—how dignity is held, and what it means to create images that both ask questions and offer sanctuary. Ferdous recently exhibited his published Sea Beach photobook at the Printed Matter New York Art Book Fair.

Aliya Nimmons: How would you explain Cox’s Bazar to someone who has never been or heard of it?

Ismail Ferdous: As someone who would go to enjoy the beach, it’s a very local beach, but still very virgin, very raw. It has changed with time. It also happens to be one of the longest beaches—almost 95 miles. I used to drive the whole way and find small fishing villages.

There’s an array of trees, pine and palm trees. When you drive down Marine Drive, Cox’s Bazar is on the right, while the hills, national rainforest, and elephant reservation are on the left. Just beyond the other side of the hill is one of the largest refugee camps for Rohingya refugees from Myanmar. Since the major influx in 2017, more than a million people live along the beach.

It’s a place where all different kinds of Bangladeshi meet—the melting pot of the whole country. The wardrobes present the culture and how this beach has been perceived by the world.

AN: How do the clothes people wear on the beach reflect ideas of class, aspiration, or cultural belonging on this beach?

IF: When it comes to what they’re wearing, people are very individualistic. They want to take their best picture in their best outfit.

Since Cox’s Bazar is a melting pot of the whole country, you might see someone wearing a very expensive suit next to someone wearing their best Chanel dupe bought for a few dollars right there off the street. It’s a mix of everything.

Looking at these kids [in the photo above], I’m sure they like the way they’re dressed up; it represents upper-middle-class family children.

AN: Can you tell me the story behind this couple’s photo?

IF: I passed this couple on the beach while another photographer was taking their picture. I asked if I could take the same picture, and the photographer said, “Sure.” I took the photos, left as usual, and returned an hour later. I ran into the same couple again, this time on the more northern side of the beach. They were walking, no longer on the horse.

I compulsively asked if I could take more pictures. After they agreed, we started a conversation about where they’re from. They explained it was their honeymoon, and I was like, “Cool—do you mind putting on your sunglasses? You had sunglasses and red lipstick, right?” I asked the woman. She said, “Oh, I rented the lipstick and the sunglasses for the picture.”

In my head, I thought, “Oh, my God.” There was something unique and bizarre about this—I realized I had photographed their dream honeymoon moment. It reminded me of the Japanese phrase ichi-go-ichi-e, which means “it only happens once.” Every moment—what’s happening right now—will never happen again.

When I work on projects like this, or street photography, I understand you can’t recreate it, ever.

AN: What aspects of the people you photographed represent your own humanity and the parts of you that viewers might not see?

IF: This photo could be an example. It’s very subtle; it’s almost a cultural reference.

This is a man from Bangladesh, from a certain class; you can tell by his glasses that he likely works in an office. It’s interesting because while that’s not me, I’ve grown up seeing people like this. Maybe he works for the government—my dad used to work for the government.

As you move through the image, you see pairs of shoes and a hat that belong to his wife and kid, revealing the gender dynamics. He’s guarding the family’s things while they have fun. This theme continues in other pictures like this—it represents certain characteristics of a Bangladeshi man that have existed throughout our history.

AN: When we photograph, we use people as mirrors—we find a way to catch glimpses or pieces of ourselves. It complements your vantage point as a native, not a passerby, but someone who insightfully documents and truly enjoys what the space has to offer. It alludes to themes of freedom and dignity. How do you preserve dignity in your photography?

IF: One of the things I wanted to keep in this series was humor. Humor has this fine line about who takes someone’s dignity. And as a photographer, I was very careful and mindful of the things I photographed. If I felt like something I photographed might not dignify that person, I didn’t use that image.

For example, I was at the Museum of Leica for my exhibition. I was alone in the museum gallery before the public announcement, seeing some of the images printed for the first time. I was quickly passing by this picture at the end of the show [pictured below], and I laughed out loud.

I’d never seen this picture at this scale. The picture itself is not funny; it was the detail. I was laughing because hair gets magnified when it’s printed large. That’s the humor. It doesn’t misrepresent him. I’m not only showing his legs, but what makes it funnier is that when I took this picture, I definitely didn’t see that.

If I did, it was in my peripherals. I say that when I take pictures sometimes, because I don’t see things individually. I kind of see it as a blur.

AN: What does Cox’s Bazar represent for you that it didn’t when you started this project?

IF: It’s the beginning of a conversation that we should be having more. This series moved a lot of people in terms of a few things: first of all, people know about Cox’s Bazar now, more than they used to. Not only because of this project, but also because of the refugee crisis that happened in 2017. There’s been a lot of UN agencies and foreigners visiting; it’s been in the news for years.

When people came to my exhibitions or became acquainted with this work, they would say, “I had no idea about this, even though I’ve been here!” I realized my series gave them a new perspective. Other people were skeptical about a photo like this [pictured below]. People start assuming, “Aren’t they gay?” I’d reply, “No, not necessarily gay.”

AN: It’s intimacy, the kind of genuine love where we see past labels. This photograph confronts the viewer and requires them to consider gender norms beyond what they know, past the singular visual expectations of men working or being active. It challenges the idea that brown men can relax.

IF: Exactly. It represents the man/man relationship in our culture. We like to hold each other’s hands, but we are not romantic. It shows a complexity that in our culture isn’t that problematic or critical.

This kind of project hasn’t been done enough. The world we present to mainstream media is not the world that we are living in. There is happiness, beautiful stories—brown men don’t have to be represented by misery. They can have a great time and take vacations.

International visual representation has failed us in a way. I can make pictures every day, but we are still missing a representation of how often we see something like this. For example, people take vacations in Nigeria, Libya, or India. In these places, you always see misery. It’s terrible because people are living beautiful, happy lives. They’re not always in crisis.

AN: Yes! Fun is universally and visually understood. In this photo [above], the details in the sand, the handmade belly button, the handprints, and the footprints that surround him show how well-traveled the beach is.

The tones and colors of your images create this utopia or atmosphere. How does color operate in your work?

IF: The tonalities speak to the counter-expectation. People tend to expect certain images coming from the middle of the world. When people see it’s yellow-toned, it’s exotic, and they associate it with India or Africa because the colors resonate with them that way.

When I was photographing, light was one of the main tools to permeate towards transcending my feelings and what I wanted to say in this series. Everything was photographed in the winter light, which is a bit cooler.

Since the beach is a prominent place, I had to be picky about what I photographed. The color could activate some emotions and my approach, but I wanted to photograph what surprised me.

Nothing was overthought, much like snapshots. Even when you look at the images, they are not extraordinarily composed. They’re very direct, or looking into details that I would maybe overlook.

AN: In journalism, images often need to prove something, and in fine art, images provoke more questions. How did you navigate that tension in your work?

IF: That’s exactly what motivated me to do this project. I wasn’t answering anyone. I’m not explaining. I’m showing you a place. I wasn’t following any rules. I was tired of only telling sad stories. I’ve done so many emotionally heavy stories—immigration, war.

I didn’t want to be someone who only goes there for pictures and leaves. After the shoot, I would go swimming in the water, have fun, go for a walk, or have an ice cream. I wasn’t just working. This project was a luxury in a way because I got to enjoy the place and also take pictures.

There are so many people and so many stories. I didn’t want to prioritize one story over another; I saw them equally and created a place in this series for them where they belong.

AN: You were deeply a part of the community that you built and photographed. If Cox’s Bazar had a voice, what would it say to the people who return there again and again?

IF: Well, it would say that it’s a place for all, a place for everyone.

It’s a place where you find yourself grounded, or find your peace and feel equal. How you restart. How you reset yourself or find connections. When you are grounded, you are connected. Come back . . . I think that’s the message.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.

Ismail Ferdous: Sea Beach is available in photobook editions for purchase online.