On Exhibition Design with Grace Caiazza

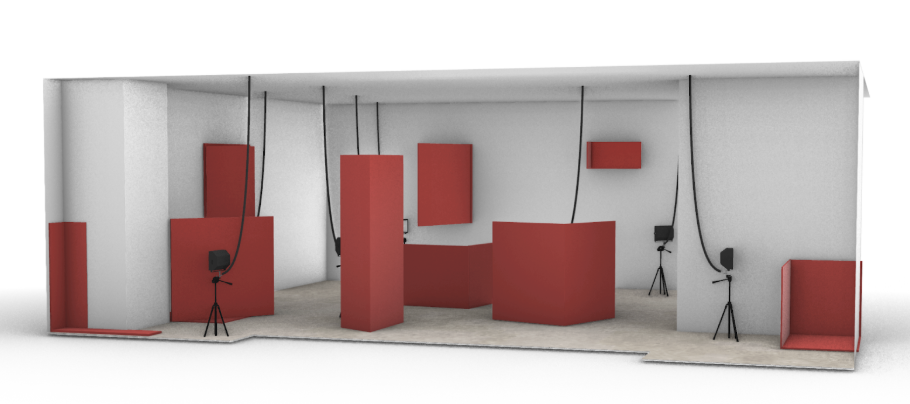

In her recent exhibition design for Arachnophobia at KAJE World, Grace Caiazza departed from convention, creating a visceral, psychologically charged environment before even seeing the artworks that would inhabit it. Guided by the theme of “phobia,” Caiazza employed cubicle-like architectural forms, theatrical lighting, and a startling red palette to construct a space that was as much a conceptual artwork as it was a container for one. The design, with its maze of sharp corners and exposed wiring, challenged the passive viewing experience, instead directing the viewer's movement and gaze to create a space of both shelter and entrapment. In this interview, Caiazza discusses her counterintuitive process, the subversion of art-viewing codes, and her practice of treating exhibition design as an art form in itself.

Yonatan Eshban-Laderman: Maybe we can start at the beginning. What is the role of the exhibition designer, and how did you approach this role in this exhibition?

Grace Caiazza: Traditionally, the way in which exhibition designers work is from the object outward, pulling your design language from the ethos of the objects you're presented with. Essentially, you try to find the hardest-hitting, affective qualities of an object and then build the world around that, and sort of exaggerate it in a way that a viewer is subsumed by the world of the object.

YEL: But in Arachnophobia, you did not know what pieces were going to be featured when you proposed your exhibition design. How did that change your design approach?

GC: Right. Instead of working from the art object outward, it was important to me to explore the space of social, physiological, and phenomenological charge and change that happens in an environment where artwork or objects are viewed. In other words, I attempted to create the container, the superstructure almost, for the act of social seeing. In general, in my work, I'm trying to reframe myself less as an exhibition “designer” and more as an artist who works with the perceptual, spatial, and interpersonal conceits of exhibitions as a medium or form.

YEL: What is one technique you employed to affect the way the audience viewed the artworks on display in the show?

GC: Take the lighting apparatus, for example. I knew from the beginning I wanted to work with very specific lights—extremely bright industrial lights used for construction sites, something brighter and with more individual sources of light than you would ever normally point at an artwork. In the show, these fixtures subtly, almost imperceptibly, cycle to a point of maximum brightness and then slowly dim, even at certain points completely turning off. The effect that this has on the artworks is to make them feel extra vivid, or hyperreal, for material qualities that can't be seen in normal lighting to appear and then suddenly vanish. Vision's ability to be distorted is so interesting to me. I really wanted the viewer to feel like the space was cyclically morphing—consistent, but still unstable.

YEL: Let’s talk about the theme of the show, “phobia.” How did you translate that abstract and psychological concept into the physical design of the space?

GC: I was thinking about how the phobic mind constantly seeks clarity, and how, as a result of that, phobia functions as a tool to create structure and rigidity. I thought about the ways in which the things we use for security or comfort, when multiplied, become destabilizing. A phobic person's mind operates to be constantly searching for and policing their own safety to an extent that it becomes extremely distorted and unhealthy. They are constantly iterating on the same basic rules and protocols, searching for and closing loopholes. Anything that is not utterly visible, exhaustively explained, and fully knowable can create a pathway for a new version of the primary fear. I translated this spatially by creating a really closed, repetitive display system where all of the component parts were the same dimensions, and where each element—the reflective nature of the acrylic, for example—acted as a kind of magnifier or multiplier of the artworks.

YEL: I assume that the attempt to interrogate the phobic mindset led to your iteration of sharp, repeated corners?

GC: Yes. I drew upon the work of architectural historian Sylvia Lavin, whose book Form Follows Libido discusses the architect Richard Neutra. Neutra was famous for making mitered glass corners to make buildings feel more limitless. My first move was the opposite; I was thinking about a series of corners, a series of hard edges, hard ends—sort of psychic traps. Spiders love corners because there are so many points of contact for them to build their webs, and in the architectural psychologic language I’m familiar with, corners are a psychically loaded space because they are a confrontation with a finitude and with a limit. My original proposal was corner-first, so you would walk into a room and see only the hard edges and corners. It proved to be a little more difficult in practice, but one demand that I had for the show was that there needed to be one purely empty, psychic corner as part of the acrylic displays.

YEL: While most of the space was governed by your rigid system, some artworks, like Char Jeré’s Propulsion Menace featuring swinging hairdryers, seemed to defy it. How did those pieces interact with your design?

GC: It was amazing to have that piece in there, because they were the thing that contested my design the most. There’s actually no way to fit them within the schema, so they were fully loose and liberated. They operated actually in a way that was very similar to my system, in that they were timed at specific intervals to create this really intense expression, but they manifested in such a feral way.

YEL: Creating such a strong, even antagonistic, environment runs the risk of overpowering the art. How do you navigate the balance between your design and the objects themselves?

GC: I think that's an interesting question. A huge part of me was worried about the artists being offended by the manipulations of light and space that I introduced. At the end of the day, they want their art to be seen, whereas my goal generally is to subvert what “seeing art” is and how it takes place. For example, you know, it’s an opening, people are having opening conversations, whatever, we know what these consist of, and then the lights go off. Everyone suddenly is disoriented. The conversations stop, and you need to reframe yourself. It's so beautiful to me. You're having a conversation with someone, you're shaking hands, and the lights go off. People didn’t know what to do. And I couldn’t stop laughing. I concern myself with the codes of art viewing, which can be really repressed, passive, and a little bit blasé. I have a deep desire to liberate it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.