Earthly Intelligence in the Desert

The earliest evidence of painting was found on the stone walls of caves. In many ways, however, the genealogy between artistic gesture and geological formation has been overlooked. Bend of the Southern Cross, Eleanor Mahin Thorp’s debut solo presentation with PLATO, returns to the fundamental relationship of painter to stone surface. The rust-tinted desert landscapes that Thorp renders in oil and stone on panel interpret rock formations, recalling ancient mythologies and material relationships to the land.

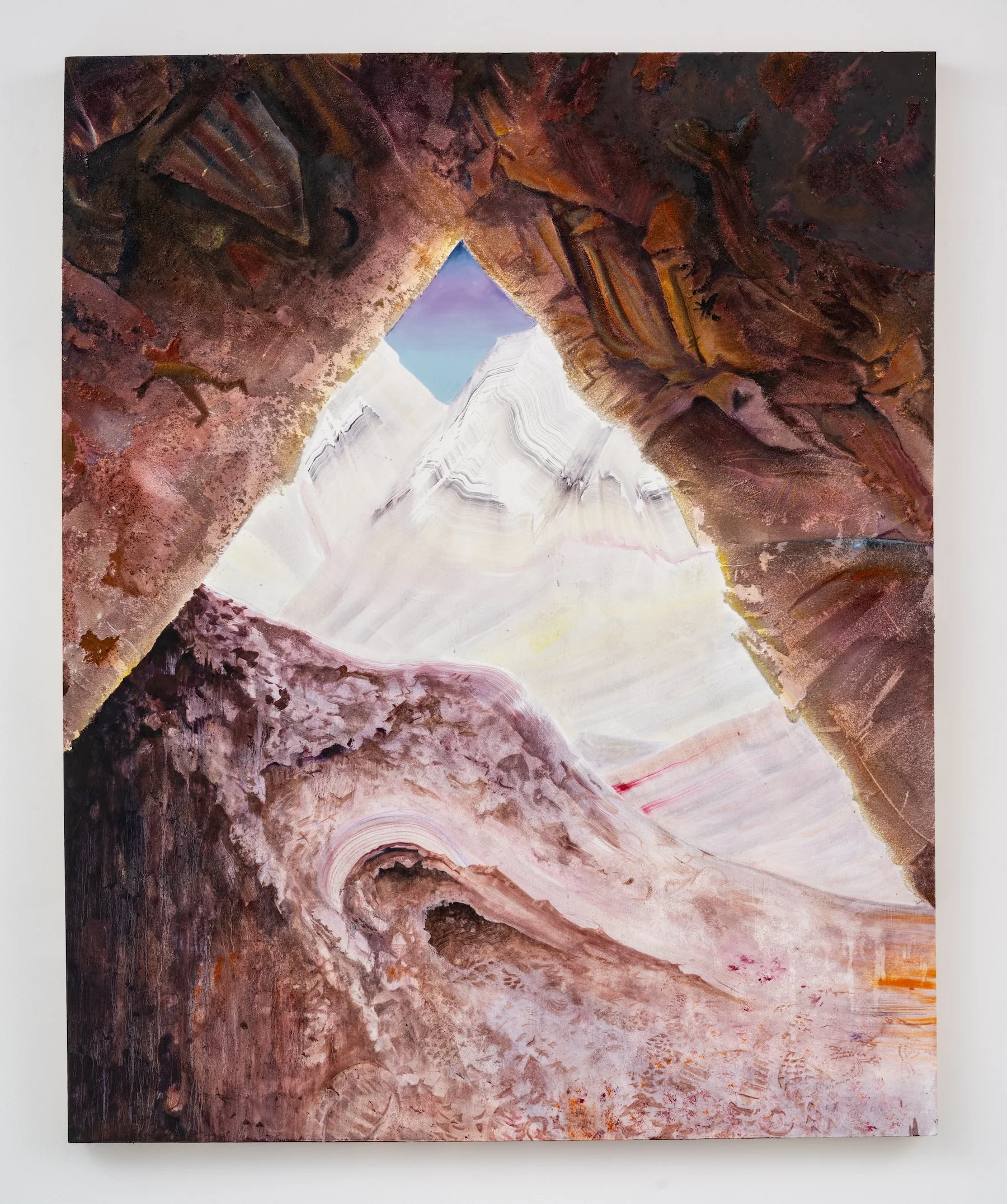

At once, these paintings feel personal and universal. Thorp focuses intently on perspective, as the process of looking through, out, under, and over is on display throughout each work. Momentum Relations, a modestly sized painting in the gallery’s second room, depicts the unmistakable, dramatic experience of looking out from a dark cave into blinding light, one’s eyes struggling to adjust to both light levels. Its triangular composition leads the viewer’s gaze up to a small glimpse of lavender-blue sky, framed in the shape of a diamond by the rock formations in the foreground. The white peaks outside the cave are abstracted in broad, sweeping motions, while the shadowy interior is rendered with tremendous texture and detail. One can see footsteps along the slanting floor ahead, revealing traces of previous hikers’ paths. Thorp takes care to depict how the stone collaborates with human hands; a rock juts out in the shape of a face, looking across the painting at a body carved into the opposite wall at an unknown point in history.

In speaking about her work, Thorp often references the Zoroastrian concept of Fravashi, wherein ancient spirits collect ancestral experiences to assist those in the material world in their continuing fight between good and evil. She sees these spirits in the surface of the earth, reading them like coffee grounds containing a wealth of knowledge and guidance for the future.

In Momentum Relations, you can see how Thorp has read the surface of the stone, interpreting each crack and deviation as an ancient message. In recreating the stone’s surface—drawing faces, shapes, arrows, and other marks into the rock—she is modeling the expansiveness of the knowledge that the earth holds. It’s hard not to see the influence of cave painting in this process; each gesture is influenced by the natural formations, as well as the particular light conditions of her time spent in that location.

Thorp’s paintings challenge the idea that human enrichment requires the destruction and dismantlement of the earth. The Atacama is rich in lithium and copper, two finite resources that are used in renewable energy technologies to power data centers and AI infrastructure. Though the desert has been thus far mostly preserved by the diligent protection of local activist groups, the increasing demand for energy has put it at risk of invasive extraction, mining, and demolition.

Downswing, with its parched, washed-out quality, suggests standing on a tall rock to view lime green lithium brine snaking, loomingly, down a desert canyon. The expanse of sediment that flattens out the top half of the painting makes way for the salty water, which forms an arrow pointing ever downward. One is struck by the smooth yet dry quality of the brushmarks that depict the brine, cut at each jagged bank by the materiality of the sediment. The otherwise straight edges of the work are disrupted by mimicked mineral formations, which hug the edges of the panel as if they have grown around it over many years. And although the neon appearance of the brine conjures thoughts of pollution or otherwise unnatural substances, the color is naturally occurring. Spending time with this painting, one is struck with the rarity of such vibrancy in nature, and the need to preserve it becomes almost immediately apparent.

In this way, the landscapes depicted in these works function both as an object of awe and as a confrontation. To mine the land’s resources would be to abandon the expansive curiosity, ancestral knowledge, and natural history of the desert in service of an unattainable, ill-defined “intelligence” promised by ever-draining technologies. Instead of unceasingly striving for vague promises of progress, Thorp asks us to value the ancient history of the land and the intelligence it already contains. She posits that the answers to our endless questions lie in the earth, its craters, and its hills. The beyond is here already, in the sky, the horizon line. All one has to do is look, feel, and listen.

Thorp underscores the expansiveness of the earth’s knowledge through her broad, sweeping treatment of boundless scenes. We Met Before Flamingos pushes against the boundaries of the panel, its symmetrical expanse of water rushing into the top two corners. In the center of the composition, the rosy pink sky is reflected in the rippling water, suggesting the perpetuity implied by a mirrored surface. Piercing the pool is a serrated peninsula, which fans out to either side past twin deltas resembling flamingo feet. The surface of the ground is dotted with constellations of canyons, ridges, and spiral jetties, sparkling subtly like distant stars.

Flamingo fossils have been found dating back more than 50 million years, far older than the earliest recorded humans. This painting, with its large expanse of mirrors and surfaces to survey, plays with the monumental task of encapsulating a history this large. It feels like a summary view of a wide field of time, anchored not in a linear fashion but in an echoing, reverberative approach.

Perhaps painting is an echo, forever bouncing off the walls of a cave. There is an ancient relationship between human gesture and geological form that reminds us where and who we came from. It gives us guidance on what to do and what to paint next. Thorp listens to the land, studying this ancient relationship through the process of depicting and preserving the desert. Her message is made evident through the resulting paintings, as her diligent practice is rewarded with an ancient, generative intelligence of the earth.

Bend of the Southern Cross was on view at PLATO Gallery until October 4th, 2025.