Knots: Ruth Asawa at SFMOMA

In Buckminster Fuller’s 1975 book Synergetics, the American systems theorist and inventor considers the materiality of a knot. Though it may be made from rope that is braided or twisted, in fibers of hemp, manila, sisal, or petrochemicals, none of these materials or methods get at the essential quality of the knot. He argues that the knot is not the stuff of cordage that it entangles, but rather the tangle itself: an immaterial pattern of self-interference; an integrity that the mind imposes on matter; a “wave phenomena” that communicates force through form.[1]

Fuller’s writing on knots is most viscerally illustrated in the practice of his student and friend, Japanese-American artist Ruth Asawa, whose works vibrate with tensile strength and kinetic flows. If Fuller looked to the natural world to inform his theory of geometry, Asawa pushed geometry to divulge organic dynamism. In an untitled print from circa 1951, the eternal lines of logarithmic spirals spring from the superimposition of golden rectangles. Slipping through the wire surfaces of the hanging, woven sculptures that she made in the 1950s and 1960s, we find pulsating rhythms of compression and rarefaction. Archival footage documents Asawa in her studio: she fans a large piece of paper, extending its compact dimensions into a truncated cone tessellated by polygonal peaks and valleys.[2] In the next shot, she flattens another sheet, collapsing the dimensional form such that only a penned-in grid remains.

Ruth Asawa: Retrospective—which opened this spring at SFMOMA and travels to New York in the fall—surveys the breadth of the artist’s career in galleries dedicated to her early years at Black Mountain College, her experiments in interior design, immersive installations of her biomorphic wire sculptures, as well as sections that bring to the foreground intimate aspects of her home-based practice, her lifelong love of gardening, and her years as an arts educator and organizer within the San Francisco community. Striking among the more than three hundred works included in the exhibition are drawings, sketches, and sculptural schemata that reveal the multifarious energies—potential, mechanical, metabolic—that permeate Asawa’s practice.

Currents and waves recur across Asawa’s work, from her years as a student to her later career. In one semi-gridded composition—made in idle moments while working in Black Mountain College’s laundry—quavering columns of ink advance across a fabric plane.[3] The same set of letters, “BMC,” is stamped in tightly packed vertical bands that alternate direction with each new line. Printed by hand, minor misalignments in the grid amplify across subsequent columns into fluent optical effects. In iteration, the letters become pure graphics: Cs interlock, evocative of links in a chain; Bs stand back-to-back like a pound symbol or four-leafed growth. The saturation of the ink varies from impression to impression, from line to line, so that the composition seems to fade and cohere again before our eyes. The lines of ink are possessed of their own vitality, media through which energetic impulses glide, like ripples on water. Other contemporaneous studies are also saturated with centrifugal whorls and meanders, both curved and straight-edged. However, her BMC-stamped prints go beyond a graphic depiction of waves to hint at particulate motion; the letters themselves become molecules in a pulsating medium independent of fabric and ink.

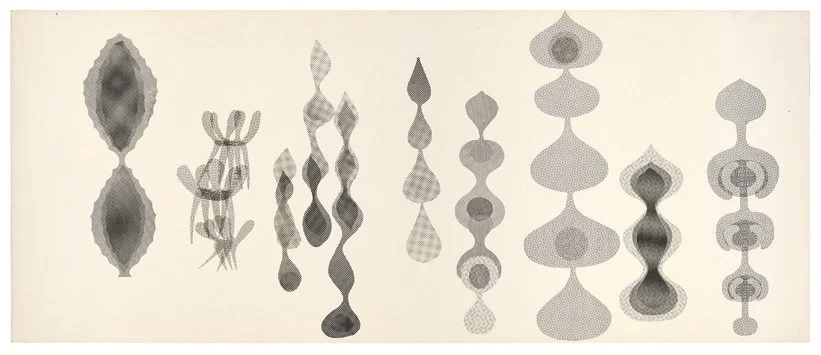

The same compressive waves course through the backgrounds of her drawings and paintings. In an untitled sketch from the 1950s, the atmosphere that silhouettes a set of seven bentwood chairs shimmers with emanating dots, the figural furniture only defined by the ink-stained ground. These undulating nets of moving marks are also present in untitled screentone on matboard collages from the mid-to-late 1950s, which the artist used to illustrate the visual effects of her hanging sculptures. In these simplified renderings of woven wire, Asawa layers speckled strata of ink to create intersecting pockets of density and interference. The contours of the collages oscillate, sketching crests and troughs.

The waving fields depicted in Asawa’s two-dimensional works are physically manifest in her wire sculptures, resiliently charged with the elastic potential of the weave. Asawa often noted that, after a point, the structures of these forms were self-guiding; though her hands knotted, building from the inside outward, the wire imposed its own constraints on her will. Conical prisms swallow each other, hourglass globules sway lobe from lobe. The sculptures collide with apparent oppositions. They are self-contained, yet permeable. The exterior contours of one become the interior surfaces of another. Suspended from the ceiling in nebulous accumulations, their outlines sketch further forms from the air, switching nimbly from figure to ground.

Asawa often related her woven-wire works to other disciplines, comparing their cycloid loops to the repetitive procedures of printmaking and weaving, the linearity of drawing (and, by extension, writing), and the toil and generative possibility of her childhood experiences in farming. In Synergetics, Fuller also compares the knot to organic processes, likening binding and its weaver. He writes:

The metabolic flow that passes through a man is not the man. He is an abstract pattern integrity that is sustained through all his physical changes and processing, a knot through which pass the swift strands of concurrent ecological cycles.[4]

Throughout her life as an artist, mother, gardener, and educator, Asawa alchemically transformed raw material into complex, closed systems replete with vitality captured and contained. Attuned to the fleeting nature of the knotted integrity of the self, Asawa described her works—such as her series of life masks, ceramic casts of the faces of friends and family—as portraits keyed to specific moments in time, gestures chasing the ephemeral. Discussing the stasis captured in those likenesses, Asawa said, “I know it’s going to go away, but I like that, I like that moment.”[5] We might think of her woven sculptures and quivering drawings and prints in a similar light. Asawa pauses time, suspending—if ever temporarily—the ineluctable reality of entropy.

Ruth Asawa: Retrospective is on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art from April 5 through September 2.

[1] Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics: Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking, in collaboration with E.J. Applewhite (Macmillan, 1975), 506.01–506.30.

[2] Ruth Asawa: Of Forms and Growth, directed by Robert Snyder (UCLA Center for the Study of Comparative Folklore and Mythology, 1978), film.

[3] Asawa attended Black Mountain College between 1946 and 1949. Supported by a scholarship, she worked in the college laundry and would often use the laundry stamp to create intricate weaves of text on paper and fabric. Asawa also worked in the college’s kitchen. Do we dare read into the rotary motions of the butter churn or wringer in relation to her repetitive, spiraling forms?

[4] Fuller, Synergetics, 506.20.

[5] Ruth Asawa, interview by Paul Karlstrom, August 10–11 and September 2, 2002, Ruth Asawa Oral History Interview, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.