A Thousand Kisses Deep: Joyce Wieland at MMFA

You can catch more flies with honey than vinegar—that adage would also apply to maple syrup, similar to honey, equally thick, sticky, sweet, fragrant, and amorphous. The sugary, non-threatening nature of this identifiably Canadian export epitomizes the strategies of charm weaving subversive threads throughout Heart On, Joyce Wieland’s retrospective curated by Anne Grace and Georgiana Uhlyarik, on view at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. The palette of the wall colors throughout the exhibition evokes a blossoming bouquet—spring purples, grass greens, pastel pinks, and blues—and employs the trademark exuberance, playfulness, and amorousness of Wieland’s oeuvre. The rigorously rich retrospective showcases paintings, films, archival ephemera, textile works, and assemblages by the artist. While the sheer variety and quantity of work posit this exhibition as formidably stunning on its own, its revelatory, uncanny relevance to our contemporary moment lies in its presentation of Wieland as a romantic radical who utilized materials and approaches commonly received as non-threatening as a disarming strategy to push forward her activist beliefs.

Wieland grew up in Toronto, extremely poor and orphaned at a young age after both of her parents died from illness; her mother passed away from cancer when she was ten years old, only three years after her father’s death from a heart attack. She was raised by her sister, Joan, who enrolled her in Central Technical School, an arts-focused high school where she studied with Doris McCarthy and learned practical skills to work in the commercial art field. Upon graduating, Wieland worked in advertising as a draftsman and then in animation, hand-painting film celluloid. This intimate knowledge of the materiality of film influenced her career tremendously and persisted as a formal and conceptual thematic as she moved across mediums, often merging approaches. Throughout the show, several rooms feature dividers made of gridded beams in the center of the space supporting films and paintings by the artist. While the exposed beams allude to the infrastructure of temporary walls often used in exhibition design, the formal characteristics also reference the modernist grid as well as the physical margins of film strips and their frames. Furthermore, the compartmental organization of the dividers corresponds with the shelf-like domestic structure emblematic of Wieland’s vanitas-like assemblages such as Cooling Room I and Cooling Room II. Inversely, the openness of the dividers presents a visual analogy to the porousness of her practice overall.

While based in Toronto for most of her fifty-year career, Wieland spent nearly a decade in NYC from 1962 to 1971, surrounded by the prevailing hyper-masculinity of the NYC art scene. These years proved pivotal in carving out a language of her own. During this time, Wieland produced several works that she termed filmic paintings. These paintings incorporated the material and conceptual devices of film and its production, such as storyboards, animation, and modeling, to name a few. On view in the exhibition, Flick Pics No. 4 (1963) and West 4th (1963) echo one another in content and composition. In both paintings, vertical rows resembling 8mm film strips cover the canvas. A row, just off the center in both works, depicts a penis repeated down the strip, its form fluctuating between flaccidity and erection. In Flick Pics No. 4, the penises share a semblance with bananas and are paired with a sinking ocean liner to the left and sailboats crossing the frame to the right. Alternately, West 4th partners the phallus with a lipsticked mouth smoking a cigarette repeated down a strip on the right and to the left, a strip of the cigarette, itself repeated, against a blue backdrop, suggesting an animated sequence of the cigarette falling and landing on the ground, the vertical storyboard reiterating this downward movement. Above the middle cigarette, Wieland writes in pencil, “causes cancer” with an arrow pointing down to the smoke. Notably, the artist painted this morbid yet relatable analogy of cigarettes and phalluses two years before Tom Wesselmann began his Mouth and Smoker series, four years before Warhol’s cover art featuring a phallic banana on The Velvet Underground and Nico, and three years before Hilton Kramer declared a “new erotic deluge” infiltrating the art world of NYC.

Wieland’s Sailboat (1967) overlaps with her filmic paintings of the early 1960s and assemblages featuring sinking boats and planes. She was particularly active in early structural film, the term penned as the title of P. Adams Sitney’s essay for Film Culture in 1969, defining the genre as having an emphasis on the material and form of film itself rather than narrative content, in which he cites work by Wieland as well as Hollis Frampton, Ken Jacobs, Tony Conrad, Ernie Gehr, George Landow, Michael Snow, and Paul Sharitz. Sitney regarded Sailboat as Wieland’s most quintessentially structural film. The following year, Sitney and Jonas Mekas along with Jerome Hill, Peter Kubelka, and Stan Brakhage, founded Anthology Film Archives, an avant-garde cinema museum made up of an Essential Cinema Repertory collection. Wieland’s work was excluded from the collection even though she was noted by Sitney as a key member of early structural film makers in New York. In a 1971 interview with Kay Armatage for Take One Wieland spoke of biased backlashed that she experienced in New York after making her first long film Reason Over Passion (1969), “I was made to feel in no uncertain terms by a few male filmmakers that I had overstepped my place, that in New York my place was making little films.”

In separate interviews, Wieland cited the origins of her filmic paintings to a small ships museum in downtown Manhattan and mentioned her general observations of an American fascination with disaster as becoming manifest in her work in the early 1960s. [1] The sinking vessels that she fixated on throughout the 1960s also present an apt analogy to the state of trade relations between the United States and Canada then and prescient to today. In a 1965 speech at Temple University, Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson articulated Canada's public opposition to the Vietnam War. The following year, Wieland began a series of plastic stuffed works that she termed hangings, fifteen in total. In one of the hangings, Betsy Ross Look What They’ve Done with the Flag that You Made with Such Care (1966), she encased an American flag in plastic. The flag drapes out of an open mouth stuffed with quilt batting. At the top of the flag, a gash in the fabric reveals a newsprint photo from the Vietnam War inserted in its void, sewn directly into the flag with visible stitching and next to it, a bandaid stretched diagonally across the red and white stripes. In addition to her opposition to the war, Wieland’s choice to use plastic and her incorporation of the mouth expresses her concern with the link between plastic manufacturing and the carcinogens and consumption it generates. Furthermore, her references to cancer in both West 4 and the pathology presented in Betsy Ross Look What They’ve Done with the Flag that You Made with Such Care hints at a literal, acute, and starkly personal awareness of illness.

Heart On presents an extremely unique opportunity to view all fifteen of Wieland’s hangings for the first time since she exhibited them in 1967 alongside quilts produced during the same prolific period. While the art world of NYC bolstered the cool and distant, apolitical aesthetic of individualistic, male-dominated minimalism and pop, Wieland explored conceptual approaches inherent to her early exposure to the materiality of film and the collective labor associated with its production. She merged this sensibility with the intimacy and collectivity of making found in textiles as evidenced in Film Mandala (1966) and The Camera’s Eyes (1966), both of which Wieland worked collaboratively across national borders with her sister, Joan, who sewed the pieces back in Toronto.

This way of working opened up a space for Wieland to tactically incorporate the practice of quilting as a distinctively feminine and communal strategy of making. In the exhibition catalog, Alicia Boutilier quotes Wieland, who said, “Getting into the making of quilts as a ‘woman’s’ work was a conscious move on my part, particularly when I lived in New York,’ recalled Wieland. ‘There was a highly competitive scene with men artists going on there. It polarized my view of life; it made me go right into the whole feminine thing.” Wieland continued to incorporate collective making in her future quilts, especially effective in the monumental works Defend the Earth (1972) and Grand Caribou (1977) advocating for an ecology of care.

Mouths along with frames of oceanliners, sailboats, and airplanes sinking to their demise appear repeatedly across Wieland's work, from paintings to assemblages to film throughout the 1960s and mid-1970s. In fact, Wieland named a body of her work produced in the early to mid-1970s mouth-scapes, describing a variety of lithographs, film, and textiles. Under this grouping, Wieland included her film Pierre Vallières (1972) which focuses on the titular protagonist Vallières’s lips, tightly framed in the composition throughout the duration of the film. In her text Jigs & Reels, Wieland wrote that she employed an extreme close-up of his mouth speaking in French in tandem with English subtitles displayed at the top of the screen, overlapping Vallières’s mouth, in order to communicate the Québécois revolutionist’s platform clearly. While English-speaking viewers would gain access to his message, they would also experience the dissonance between the words spoken and the text read, emphasizing the sound of language as material in and of itself. The film is organized into three speeches prepared to coincide with the duration of a film roll, roughly ten minutes each. Vallières critiques the Canadian government’s complicity with US extraction for capitalist profit and advocates for liberation and solidarity across race, gender, and class, at points faultily conflating plights of oppression. The film ends with Vallières calling on the people of Quebec to take accountability, as the descendants of Nouvelle France, for the genocide of Indigenous people. In a column for Village Voice that year, Mekas praised the film as the most successful political film he had seen.

In the exhibition, Pierre Vallières plays on a screen juxtaposed in front of Betsy Ross Look What They’ve Done with the Flag that You Made with Such Care (1966) and Flag Arrangement (1970–71), a series of four knitted Canadian flags made by champion knitter Valerie McMillin who Wieland recruited to recreate the Canadian flag, adopted only in 1965 as the country’s first official flag. In each flag, McMillin used the same number of stitches but employed different stitching techniques, yielding a diverse, abstracted assortment of the flags which reiterate the plurality enveloped in not only Canadian identity but the abstract and mutable (yet specific) nature of identity more broadly.

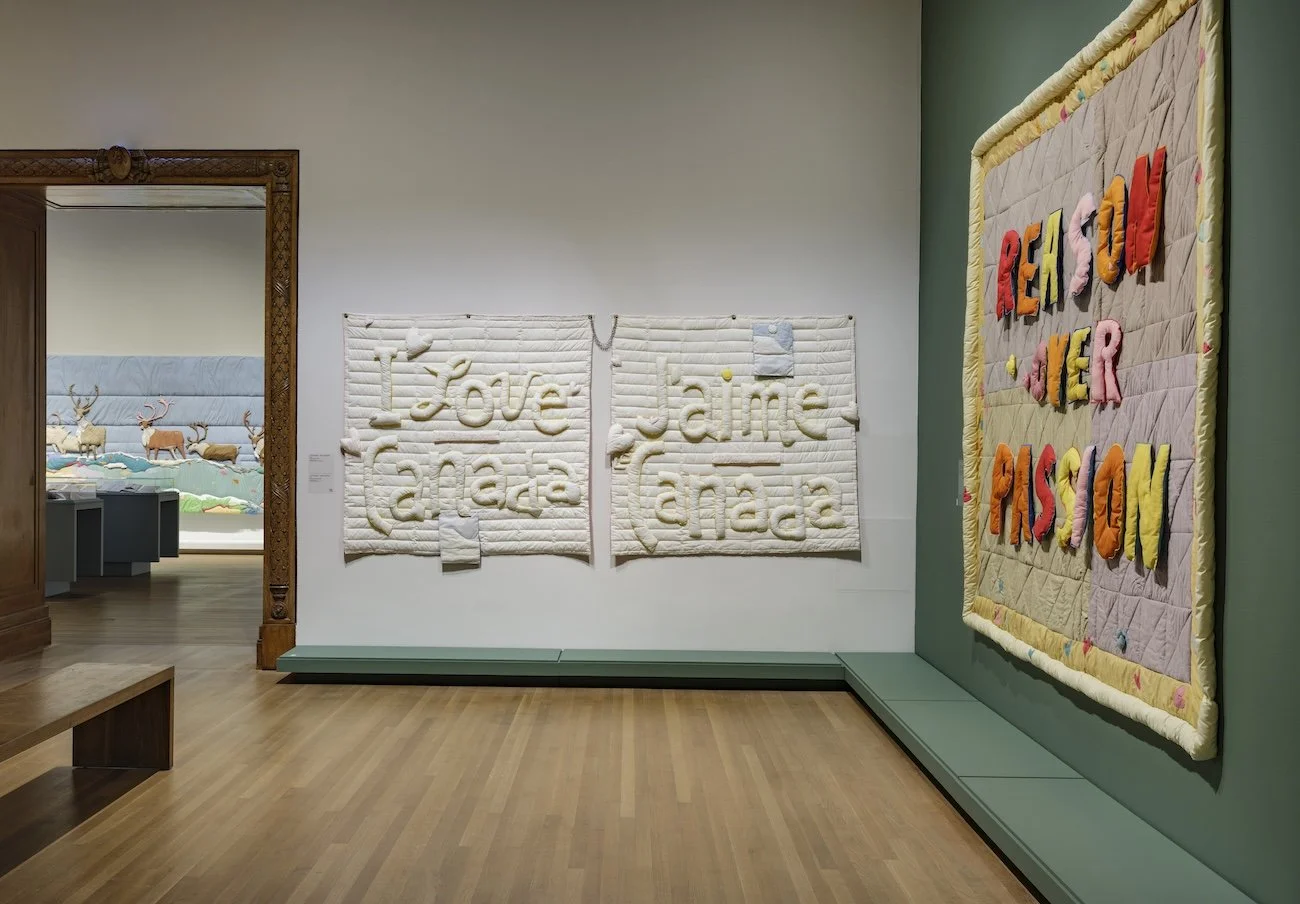

In Reason Over Passion (1968), Wieland adopts Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau's (father of recent Prime Minister Justin Trudeau) motto “Reason Over Passion.” The elder Prime Minister Trudeau repeated this phrase often in speeches and conversations with the press. Wieland’s bright letters framed by emotive, colorful hearts puncture the stoic undertones of Trudeau’s motto, suggesting that passion must coexist with reason and implicating the discriminatory and oppressive underpinnings of so-called reason as a patriarchal, colonial tool. Put plainly, conceptions and receptions of reason and passion are framed differently depending on gender, race, ethnicity, and class—particularly relevant to our contemporary moment as rhetoric and aggression are positioned as charisma and power while notions of reason have become increasingly mutable and polarized.

In I Love Canada/Je t’aime Canada (1970), also made in collaboration with her sister, Joan, Wieland declares her ardent adoration for and devotion to her country in lovingly quilted bold, bubble letters. Wieland conceived of the bilingual work one year after Canada adopted French and English as its two official languages. Slyly stitched with tiny light pink thread into the white background surrounding the buoyant letters, the phrase “death to U.S. tech imperialism” and, in French, “A Bas L’impérialisme Technologicque [sic] des E-U” almost hidden from view, quietly proclaims her fierce protectiveness of her country from the threat of U.S. expansion, extraction, and exploitation. Sewn by her sister in Toronto, Wieland passed this subversive design for production across borders. The following year, Wieland moved back to Canada, the same year that President Richard Nixon imposed a 10% tariff on all imports into the US.

While Wieland’s criticism of US dominance in the early 1970s proves applicable to our current context, so do undercurrents of erasure dealt by the hand of nationalism. Even within Wieland’s strident critique, her strong yet effervescent love and protective instincts for her nation also whitewash the violent and genocidal history that bolstered the Canadian nation and wider North American nation-states into being. The metal chain connecting the English and French versions of I Love Canada/Je t’aime Canada symbolized a joining of two cultures in unity against US influence at the time the work was made, yet, in light of the absence of Indigenous presence in the work, the chain takes on a violent tone in retrospect, particularly against our own contemporary backdrop.

That said, Wieland showed interest in Inuit narratives during this time, as evident in The Great Sea (1970-1971), a hooked rug work on view in the exhibition. [2] Initially conceived of as a triptych adaptation of an Inuit song told from the perspective of Uvavnuk, an oral poet who had a shamanic experience after being hit by a meteor, Wieland wanted to translate the song into English, French, and Inuktitut text across three panels. Translated by Inuk poet Tegoodligak, the song titled “Aii Aii” reads:

The great sea has set me in motion set me adrift

and I move as a weed in the river the arch of sky

and mightiness of storms encompasses me

and I am left

trembling with joy.

The song encapsulates what Heart On puts forth as the quintessential threads connecting the total arch of Wieland’s oeuvre: her commitment to women, nature, and mystical acts of love and devotion. The song also opens the artist book publication True Patriot Love, on view in Montreal, that Wieland made for her solo retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada in 1971, the institution’s first retrospective of work by a living female artist. In the artist book, Wieland pins the song in Inuktitut over the first page of a government publication introduced with the heading “Illustrated Flora of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, Introduction.” Wieland included the song in English and French in the following pages accompanied by images of The Great Sea all pinned on top of and interrupting the bound printed publication. The pin references textile practices and their power to intervene, mending the educational government text.

Also part of the “mouth-scapes” body of work, Wieland executed a series of lithographs that she termed lipstick or lip-synch prints, describing them as lip-animation from 1970 to 1974. [3] One of these lithographs on view, The Arctic Belongs to Itself (1973), comprises a series of lipstick imprints sounding out the titular phrase accompanied by block letters spelling out each syllable. As is common in cultural associations with land, Wieland thought of Canada as a woman, and the employment of her body in the work presents a parallel between land sovereignty and personal sovereignty. Made via overt sensuality, the shape of Wieland’s mouth, pressed against the lithograph stone, resembles icebergs, the top part rising above the water, the bottom submerged.

With a strong interest in labor rights and ecology, Wieland’s engagement with the Arctic evolved over the years as she reconsidered the conflicting tensions of her subjectivity as a white anglophone southern Canadian woman advocating for the sovereignty of the Arctic North while also championing it as a core part of Canadian identity to be protected against the threat of US imperialism. Wieland’s artistic conceptions of the Canadian North were inextricably complicated by settler colonial biases embedded in depictions of the Arctic that she would have been surrounded by growing up in the South; she visited the Arctic for the first time in 1977. In her exhibition catalog essay, Facing North, Uhlyarik quotes Wieland discussing her experience in a 1981 interview with Lauren Rabinovitz, “She also shared her observation of the ‘deep division’ between Inuit and settlers: Inuit ‘living under the restrictions of a white person’s home made it impossible to bridge the gap . . . Bridging that gap is something a lot of whites think they have done, but they’re kidding themselves.’”

In the quilt Lens (1978-1979), Wieland quotes a poem by Anne Wilkinson of the same name; this is the last work of Wieland’s in which she quotes anyone. Wieland packs the letters from the lines tightly, breaking up the original organization of the printed poem, which reads:

The poet’s daily chore

Is my long duty;

To keep and cherish my good lens

For love and war

And wasps about the lilies

And mutiny within.

MMFA’s Heart On generates dialogue on care and identity, meeting our moment as North America reckons with its own conversation on unity and division, accountability and erasure. The petulant whims of the current “I’m rubber, you’re glue” US administration continually push for isolationism, smashing away at their own tower of blocks. The resulting chaotic tumult of North American relations and global networks more broadly won’t bring about prosperity; yet, it may actually bring to the fore a stronger awareness of the precarity of sovereignty as well as its contradictory fallibility and, perhaps, an interdependent, dutiful revival of tough love and tender care.

Joyce Wieland: Heart On will be on view at MMFA through May 4th, 2025.

Notes:

[1] In her catalog entry on Sailboat Sinking (1965), curator Anne Grace cites Wieland references to this museum in an interview from 1981 with Lauren Rabinovitz quoting her, “There was a tiny downtown museum, The Ships Museum, that I used to go to often. The filmic paintings started to revive then—so much of my work was already influenced by making animated films, doing storyboards and a lot of things that were serial.” Wieland, Joyce, Art Gallery of Ontario, and Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. 2025. Joyce Wieland: Heart On. Edited by Anne Grace and Georgiana Uhlyarik. Toronto, Ontario: Art Gallery of Toronto; Montreal, Quebec: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; Fredericton, New Brunswick: Goose Lane Editions: 93.

In Renée Van Der Avoird’s catalog entry on West 4th and Flick Pics, Van Der Avoird quotes Wieland’s comments on American fascination with disaster showing up in her work from an interview with Jonathan Holstein from 1964. Ibid. 83.

[2] In her catalog entry on The Great Sea, curator Georgiana Uhlyarik cites that Wieland contacted Evelyn Mombourquette Aucoin to make the work. Ibid. 190.

[3] Wieland refers to the mouth-scapes in her text “Jigs & Reels” published in Form and Structure in Recent Film (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 1972), unpaginated.

Edited by Xuezhu Jenny Wang