Porcelain and Power: The Female Body in Jessica Stoller’s “Split”

Jessica Stoller’s latest solo exhibition at P·P·O·W Gallery, Split, is a deeply layered examination of the feminine body and control. Working with porcelain in an alchemical process of layering china paint, glaze, and sometimes metallic luster, Stoller creates sculptures that feel at once sensitive and grotesque. The works in this exhibition revel in contradiction: soft, fleshy colors animate hard ceramic structures, while in other pieces metal elements mix with porcelain forms. Stoller’s mastery over material results in a world where ornament and organic matter merge, exposing both beauty and violence.

In her previous solo exhibition with P·P·O·W in 2020, Spread, Stoller used porcelain to link its cultural context of desire and taste to the shamed female body. Displaying what is taught to be hidden—nipples, pimples, wrinkles—she played with what is explicitly said in the control of women and what is silently agreed upon. Where the exhibition title Spread referenced the rarely celebrated or displayed vulnerability of feminine bodies, Split appears to be referencing the paradoxical female experience. This new body of work is an insightful and exciting development of exploration that feels admirably honest in both experience and critique.

Immediately to the left upon entering the show, viewers are met with the focal piece, Seeing Red (2024). Its grounding tiles and many components operate as a medley of references, pulling from art history, medical anatomy, and feminist theory. Bernard Palissy’s ceramic platters are referenced through the inclusion of frogs, snakes, and foliage. Its surface is also crowded with strewn shells, underwear, and body fragments—feet, hands, pelvic bones—all rendered in ranging shades of fleshy pink and raw red. Here, natural forms intertwine with reproductive health symbols—pregnancy tests, calls to anatomical models, and even hangers. Stoller found inspiration in anatomical venuses, wax models of women used in the 18th century for medical study, which often wore pearls. Most notable in Seeing Red are the large pearls meticulously placed amongst the chaos; this act of throwing the pearls onto the ground calls into absurdity the exaggerated femininity through ornamentation of women’s bodies, even in a post-death implication. In this piece, Stoller makes visible the often-hidden violence and control enacted upon reproductive bodies, calling into question the relationship between life and artifice, preservation and decay, and domination and subjugation.

In the rest of the exhibition, through tiled pieces along the walls and ceramic sculptures on pedestals, we see Stoller’s deep research into medicinal plants once used as contraceptives, such as rue, pennyroyal, and silphium. These pieces highlight her engagement with Silvia Federici’s seminal 2004 text, Caliban and the Witch, emphasizing the loss of both nature and women’s bodily autonomy through industrialization and capitalism as it erased or commodified natural contraceptive methods. There is a clear acknowledgment of female self-determination being as natural and necessary as life itself.

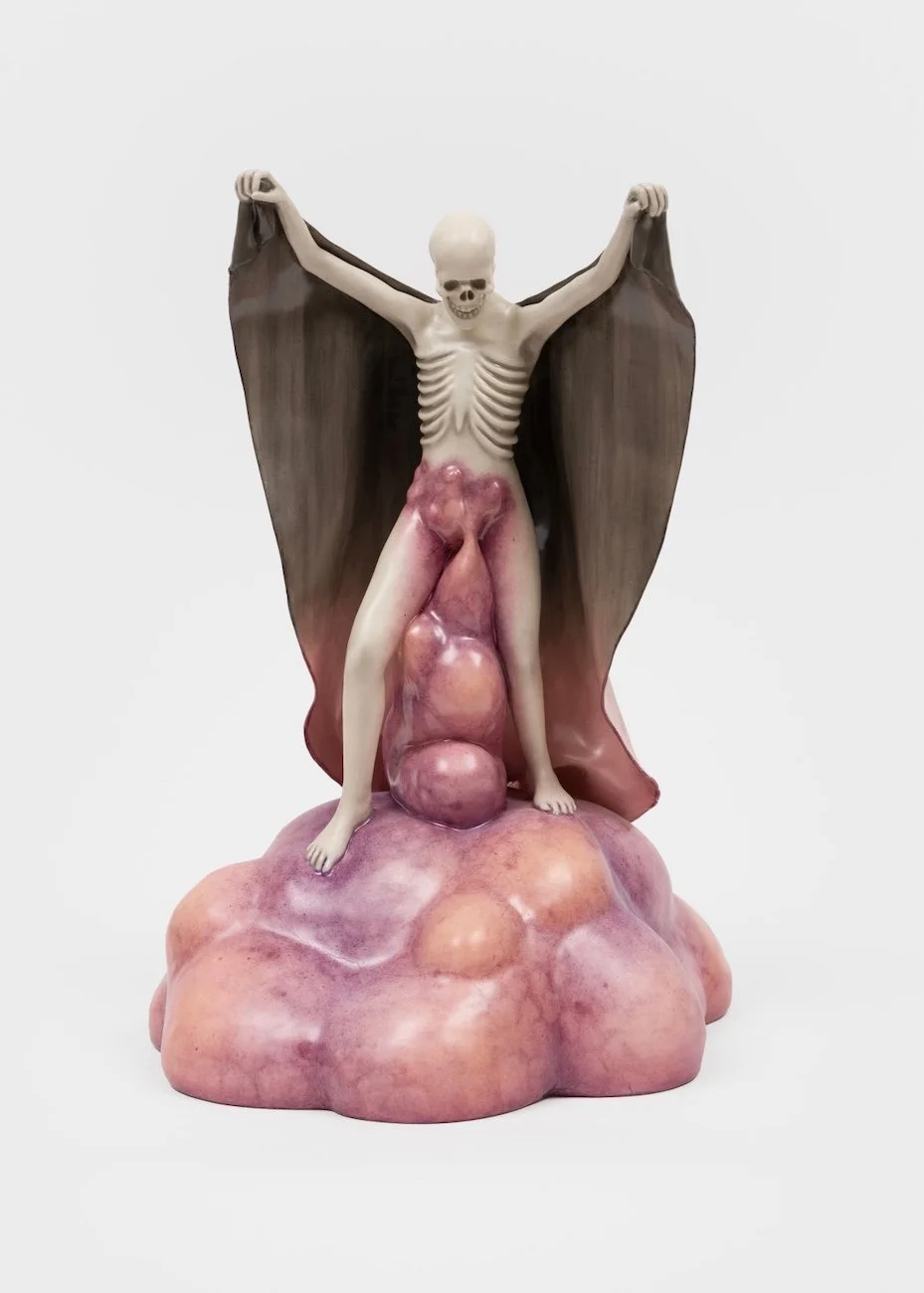

A reimagining of transformation echoes throughout the exhibition, where Stoller’s expert manipulation of porcelain pushes the material beyond its traditional associations of fragility. She continues to explore aging as she began in Spread: in Untitled (crown) (2021), we see the transformation of hair greying and in Skin to Scale (2023), the act of shedding skin and growth comes to mind. These visuals adorned with intricacies of beautifully winding snakes and braids reconceptualize the act of aging as elegant and freeing. Seen at the end of a hallway, Mirror (2024) from a 20-foot distance initially appears to be a skull, but approaching it closer reveals the cradling of two ghostly fetuses. This ominous reminder of mortality embedded within the cycle of creation is prevalent in other works on the table, such as Multiply (2024), where a caped skeleton births cancerous, bruised growths. As mentioned before, this exhibition brings to light the contradictions between control and autonomy, life and death, beauty and violence. Using corporeal, violent, or even grotesque visuals within this medium points to the contradictory experience of women in today’s landscape, specifically in regard to their bodily autonomy—highlighting both the power in womanhood and the body’s capabilities, as well as the undeniable violence and control consistently enacted upon them.

Like an alchemist laboriously reconstructing the elements, Stoller invites viewers to look closer, to see the layers beneath the polished surface. In doing so, she forces us to confront the history and politics of the patriarchal structures that continue to shape our perceptions and attempted control of female bodies today. Through extensive research and innovative execution, she delivers a show that should not be missed.

Split is on view at P·P·O·W Gallery from February 28 to April 5, 2025.

Edited by Jubilee Park