Studio Talk with Eva Tellier

Ten years after having shared an art table in high school with Eva Tellier, I find her at a new workshop table at Sculpture Space in Queens. We sit for a moment, reconnecting, as we consider her journey here from Paris via Montreal, Denmark, the South of France, and upstate New York. At 27, the French-Australian artist is no stranger to new environments and is eager to learn from them. Tellier began with drawing before moving into fibers, biomaterials, and now ceramics, exhibiting in Denmark, Canada, France, and the US. Her 2025 thesis show at Alfred University, ant/i/bodies, explored matriarchal worlds through hybrid forms of human psyche and insect anatomy. Grand in scale yet intimate in effect, her work exposes what is usually hidden, blending science-fiction sensibility with vulnerability. Constantly adapting, Tellier imagines alternative universes that collapse binaries and allow her themes to coexist.

Danaë Petsimeris: What’s the starting point for your fascination with clay?

Eva Tellier: Each material expresses something in its own way. Everything I make starts life in clay, as a prototype or a form. Clay is versatile, flexible, and forgiving; it is also fleshy by nature and intuitive in the way it takes shape, unlike, say, metal, which you have to forge or cast. Clay is instant. You touch it and it gives. The urgency of the material means that you have to care for it and always be present. That’s part of the investment and attachment that a lot of people feel towards clay. I wouldn’t say that clay is more important than any other material, but it’s the most intuitive.

DP: Your recent work has come a long way from earlier pieces that more clearly served a utilitarian purpose. Is this deliberate?

ET: I do think that material culture is an extension of ourselves. Furniture and everyday practical items are of interest to me. The last piece I made was a pair of shoes—a functional object. It’s technology for walking on the hard ground we have made; it’s related to our (com)modification of nature. A pair of shoes is also part of the technology of gender and identity. It is a good example of something utilitarian in the sense of the ideas it embodies, along with the strict function of the object. It’s more a reference to the ideas in use, the shoes’ narrative. There is a lot of art that doesn’t involve objects at all, but objects are a huge part of my interest. They’re vessels for narrative.

DP: Your more recent work seems to be entering into play with aesthetic divisions, particularly those between abstraction and figuration. Could you speak more about this evolution?

ET: I never separate the process from the conceptual idea. The reason I make things in three dimensions is that the making is so important. The impulse to create is not just about making with my hands—it’s about an image or an idea coming to life in front of me, in interaction with me. Whatever I see in my head, I’m excited to see develop in real physical form. That’s what I mean by the concept being married to the process, but the making is what brings me so much joy. I don’t think I’ll ever be a conceptual artist detached from my material—for me, there is not really a distinction between them. The performativity of materials is what is interesting to me. Textures and emotions are important: what is sticky, or slimy, or soft, or hard. Terms like abstraction or figuration don’t really come into it.

DP: That reflects what I’ve always known about you: you’re spontaneous and like direct contact. Is there a connection between your personality and ceramics?

ET: Yes, and I think this is in relation between body and movement. I often ask, Why clay? When I was young, I wanted to be a dancer, to be expressive through motion. That didn’t happen, but with clay, this material dances; it moves in all types of directions. Clay is expressive and gestural—it’s like drawing, but in three dimensions.

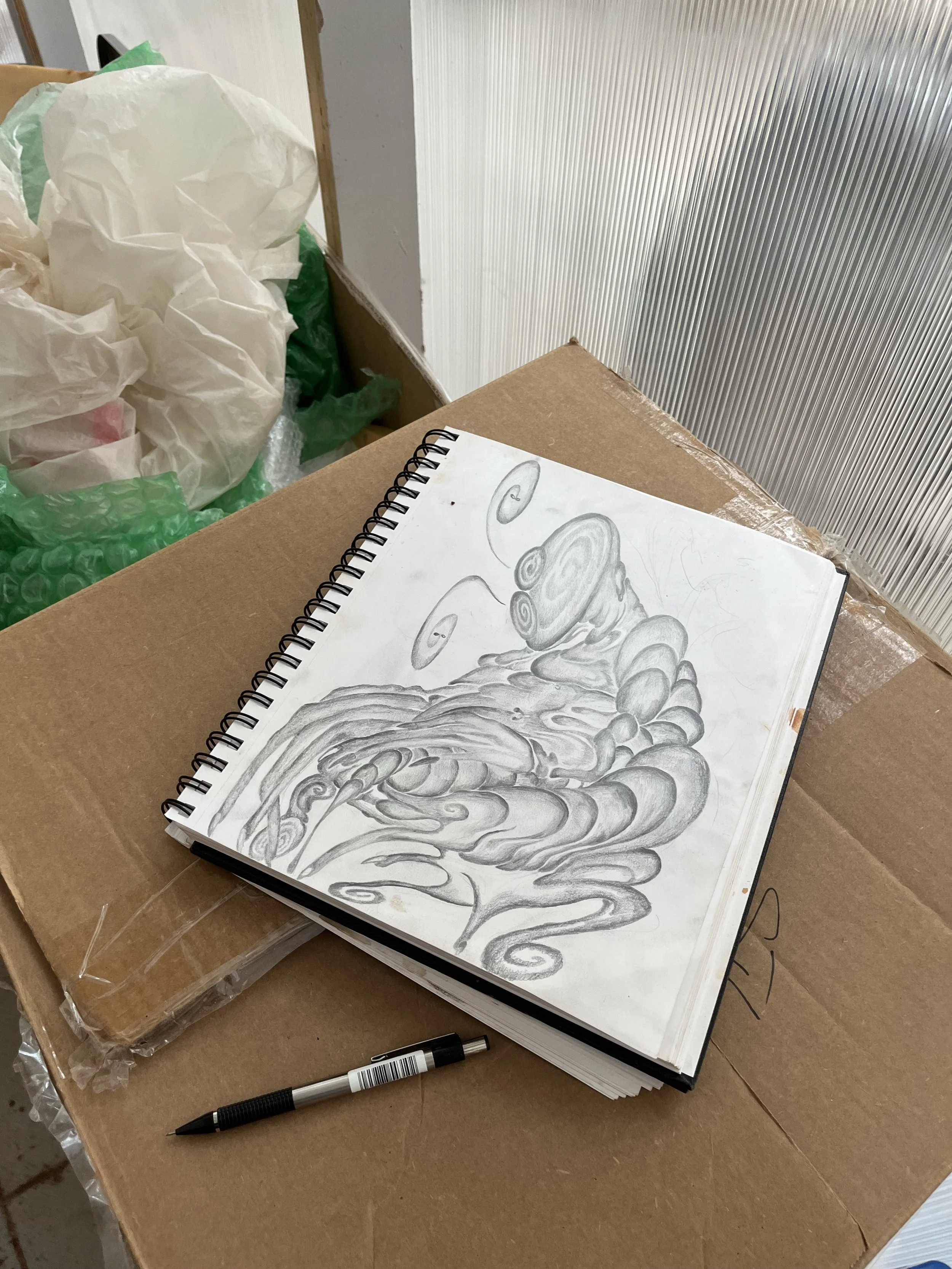

DP: Looking at your workshop table and your sketchbook, I see that you mix words with drawings, and many of your sketches seem to be works in progress. How do language and craft exist in your approach?

ET: Being bilingual (French and English) helps certain boundaries collapse more easily. Language and image get entangled in my brain, and lead to a more emotional representation of something I’m trying to convey. I wouldn’t say that the idea comes first—it’s intertwined with the process of making. References and influences that I have from the places I’ve lived comprise a library of visual aesthetics that I store in my brain, but the subconscious is always there, too. Sometimes I have a clear visual of what I would like something to look like, or sometimes I have a word or a sound that I would like to make three-dimensionally. But I don’t draw or sketch out every detail.

I’m interested in making things in fragments and multiple parts. I’ve come up with this method of working that generates forms in a certain way. This is by a series of additive processes that I then subtract from. Forms also emerge from that sort of subtracting of material by carving out or cutting out in the clay. But I think that cutting into a single part of one unit to reveal multiple ideas is a recurring theme. With language, I do the same: within one word or one etymology, I try to see the whole range of meanings that it can have for different people. Language becomes images in my head. It is almost a synesthetic experience for me.

DP: Now that you’re at Sculpture Space, what will you be working on?

ET: It’s amazing to be in a new space. I don’t know what it’s going to bring, but I do know that making a work in the city is different from making one in the country. I was in the same place—Alfred, New York—for two years, and it allowed me to develop my own aesthetic language and series of making processes.

Here, in the city, things are going to have to shift. From a purely practical point of view, the kilns are smaller. I’m interested in the opportunity afforded by this type of constraint because it’s going to turn me towards more modular making and pieces. I’m thinking of all these marionettes I want to do that are deconstructed bodies comprised of multiple parts linked by metal, jewelry-type attachments. In Sculpture Space, I will make the skeletal parts out of clay and work on the different materials I want to incorporate into the ceramic work. I plan to create a silicon shoe strap for a pair of stilettos I made. I’m also thinking of other furniture, such as monstrous duck springers in playgrounds, adult play and sexual games, and furniture that would not be useful to sit on, but which the human body would embrace. I have two months here—it’s short, but a lot can happen in that time.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.