Regenerative Skin: In Conversation with Austin Kim & Jerome Wang

...not a science, not a prayer, but a reach into the blackened dark…the warmth of a membrane founded in pure discovery. Amorphous, squinted, protected, a Living Skin.

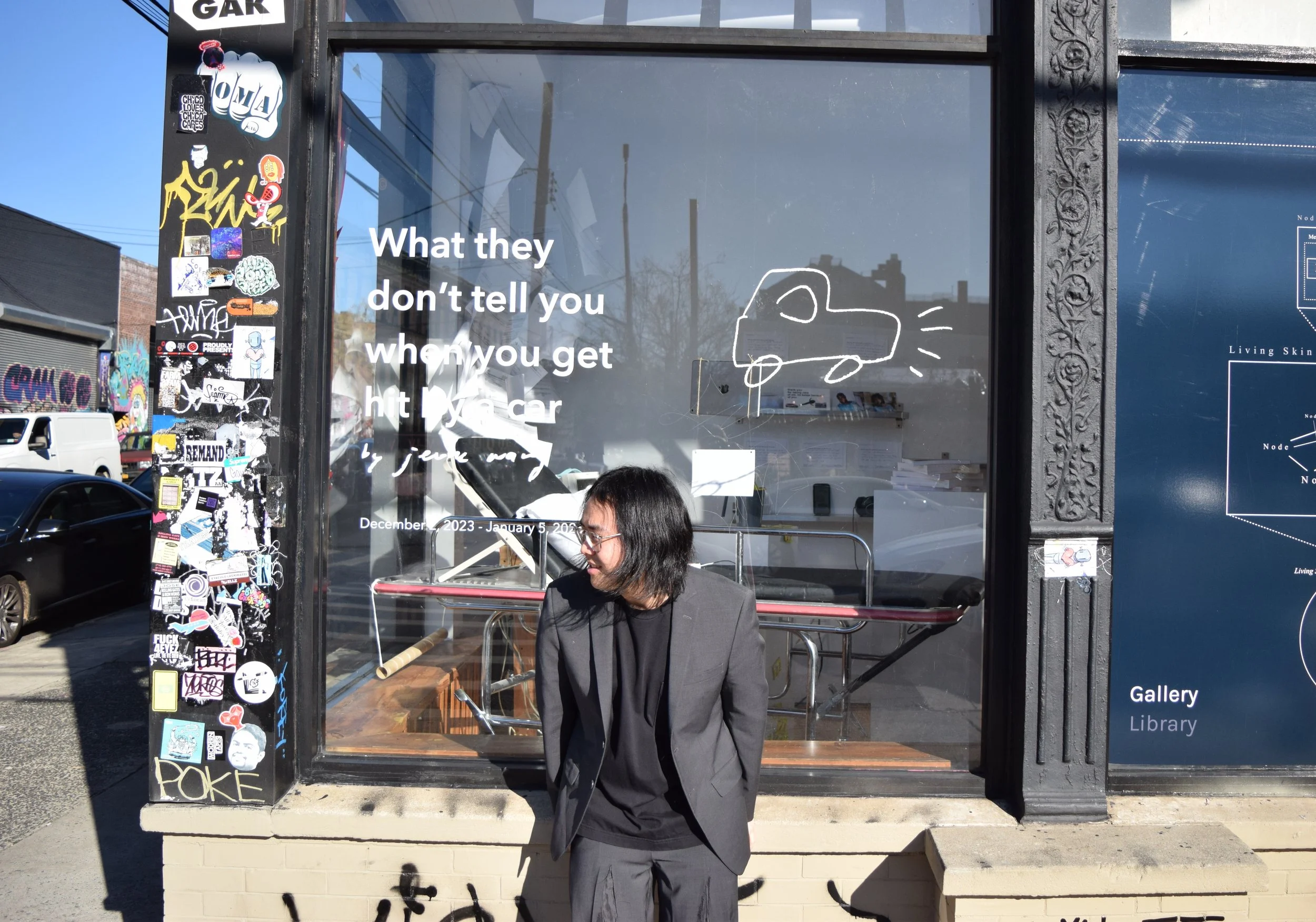

For the past two years at 61 Wyckoff Ave in Brooklyn, Living Skin has been the home of Austin Kim and Jerome Wang, two curators without a background in art who’ve been running and living out of a unique gallery/storefront that completely defies typical understanding of how project spaces operate. For the aptly-named Living Skin, the best way to describe their lasting condition would be as a continuous state of experimentation, transformation, and regeneration.

It’s a rarity to find a space that’s so anti-commercial, self-sustaining, and untethered in its context to any external trend, scene, or discourse beyond what its own ethos embodies purely in and of itself. The sacrifice required to commit oneself entirely to a shared front-facing practice, guided by an all-consuming liberty of ideas and mutual passion, and without any prior education, reputation, or expectation in the field, is one of the most daring undertakings in any field. There is a singular potential that is unlocked when people enter a situation where the only path to survival is to create something truly miraculous, seemingly out of thin air. That is what Austin and Jerome have achieved with Living Skin, over and over again.

As Living Skin now transitions to a new home at 9 Monroe St. in Chinatown, I spoke with the founders, Austin and Jerome, about their head-first plunge into the art world, what they’ve learned from the experience, and how they see the future unfolding.

Connor Sen Warnick: Tell me how you two ended up in this space, and what was it about the space that originally called to you?

Austin Kim: There was an apartment off Myrtle-Wyckoff that we both liked enough. We settled on it, and I was walking over to sign the lease on the place when I got a text that one of my saved listings was open for touring. The photos were really bad, like you had no idea what this place was. It looked like an enclosed dungeon. But I remember walking into this new place and I totally lost it. I called Jerome immediately, who was in Wyoming or something.

Jerome Wang: I was in Utah studying, like a week before my MCAT. Austin called me and said we have to sign this place. And I think I just wired him $6000 and told him to put it all into that deposit. Let’s just get this place going.

AK: We knew it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

CSW: How did you conceive of Living Skin? How did you envision it in the early days, while maintaining it as your home?

JW: There was a lot of training to get from this becoming something called Living Skin to us actually being there. For two months straight, we were staying up for hours past midnight every night, talking and throwing around ideas. Austin wrote so much—that was a big part of the practice too. Looking back, we probably looked outside ourselves too much in the beginning. There are so many things around here—so many studios, spaces, galleries—and people do such a good job. We were combining graphics and research, creating this perfect amalgamation—something that’s like stat-maxxed. And I think at that point you’re just making a chimera of all these certain things. But you’re not creating something for yourself, you’re creating something more purposeful, targeted.

AK: I think when we first started, we were looking at it like a research, design, art practice space or something like that, but it was never really focused on being public-facing, per se. In its purest form, it was always a creative exercise between me and Jerome. Research and design we had experience in—but in art, zero. So we never, even to this day, very rarely between us, used the word “gallery” when describing this space. It’s always “Living Skin” first. And we’re still figuring out what that means. We wrote this manifesto that was launched with the opening of the space. And that was the first time, at least in my life, I wrote about how to understand art—what it could mean to someone who knows nothing, or someone born into it.

CSW: Were there ever challenges with keeping the boundaries while living here?

AK: Oh yeah. I don’t wish that on anyone. I try to be conscious about dwelling on this, but honestly, it was pretty tough living here after a while. For one, the noise is crazy. The windows and walls are incredibly non-soundproof. Our third roommate was the Wyckoff Ave drunks and smoke shop speakers. If we didn’t have our curtains up, then we were exposed directly to Wyckoff. It’s very naked. So many times I left my room to take a shower, too lazy to put on clothes, and people fully dressed for a night out could see a dude in his boxers walking around like it’s an aquarium. It perverted my understanding of privacy and the need for it.

JW: The most taxing thing was whenever someone would come in and it would be a huge spectacle, like: “Oh, you live here too?” and that was always the most grating thing. If you made a Venn diagram of what makes a good home versus what makes a good public space, there is no intersection. It’s just two O’s.

CSW: Did you ever encounter feelings of doubt about how to sustain this practice while living in the space?

AK: Yeah, at the end of year two, where we are now, I’ve been asking myself that question a lot. Partly because of burnout, but also the financial burden of it. It’s a real estate problem at the end of the day. And l’m thinking again about how that beginning wave took us over. I approached it more intensely than anything I’d ever done in my life, dedicating every waking moment to one cause. Together, we fulfilled a possibility, the 100% capacity that’s achievable when every waking second or minute, with no breaks, is dedicated to something.

CSW: Are there particular events or memories that come to mind from 2024 as being particularly emblematic?

AK: Tapas (2024) was one of our biggest projects. It was this incredibly fast, one-week-turnover per artist show over six weeks. And then in the seventh week, we took everyone’s work and combined it into a big group show. That took over our rooms. The bathroom, fridge, and cabinets were all used. We had stuff outside on the stoop. That was the first time we maximized the space. From there, the blitz over the summer really set the tone for the whole year. Week after week after week, no time for breaks. That meant staying up until 3-4-5-6-7 AM every night working. So many late-night memories. We did that a lot, probably can’t do that anymore, but it felt easy, it really felt easy.

The whole first year, we just blitzed hard. And that’s all we were doing, we did not stop. We had fourteen total projects: ten shows, three residencies, and one end-of-year conference. I got kind of addicted to that feeling, that completely open-door policy, always working out in the open.

CSW: Do you feel like making Living Skin gave you a new way to express yourselves that maybe you didn’t have before?

JW: Yes—I was definitely creatively repressed before this. I feel it now the most, because I’ve stepped away for a bit and paused because of med school. I didn’t realize how much it’s really impacted me, and how much this meant.

A lot of people have a lot to say and a lot they want to do, but when you get the test, you’ve gotta perform. And for us, our test was so public. Everyone who’s walking down the street sees what we’re doing. We’ve had shows people didn’t respond well to, but that was beneficial, too. I know we’ll never be tested like we were here again. But in the same way, we had nothing to prove because we had no background or pedigree. It’s different now because there are expectations. I don’t know if it’s the right word, but it’s hard to be hungry for something for such a long time. There’s now a baseline of what to make and what people expect, and sometimes that’s detrimental.

CSW: So, I know that the plan is to move into a new space. What does the future of Living Skin look like?

AK: Living Skin is joining with three other curators/project spaces in a new location in Chinatown. The new space opened on October 10 in Chinatown. All of us are ready to cultivate a narrative for what shared and alternative spaces mean for artists, curators, and galleries, while also exploring more specific independent ventures for each of our projects.

The name for the curatorial partnership and space is Ni Ne, pronounced “nee-nay.” The group came together in just a few weeks, the same way Living Skin was formed in a short amount of time. It seemed like the only way to go. And I won’t be living with the space anymore, so it’ll be a much purer practice. Fewer distractions, more shared time with other people there.

CSW: Who are the other curators and galleries that will be joining you?

AK: There’s Seoyoung Kim, an independent curator who runs Site, her nomadic curatorial practice. For Nine, Seoyoung is starting up a new project called Service, as more of an artist residency program. There’s Jordan Segal, who’s running Curmudgeon, an apartment gallery in FiDi, who’s also a practicing artist with very prickly sculptural work. Then there’s Blue Boy, a gallery in Savannah, Georgia, run by Phillip McClure out of his backyard shed. Seoyoung and I have been good friends for a bit; Jordan, I met through mutual friends and really admired his quiet will.

CSW: Are there ways in which this new move could improve or open up new possibilities for Living Skin?

AK: Seeing the new place with these new curators, I’m definitely very excited. Long-term, I don’t like thinking about projects with a one-year expiration date. So, probably by the end of next year, I’m going to have the question answered of whether this is going to be a life-long commitment, or to end it in whatever current capacity it’s in.

I think the aesthetic property of Living Skin will be much better protected by not living there. Having more mental distance is good—it’s not just the people peering into your window or knocking on your door constantly, it’s the possibility of having separation from the space and yourself. We didn’t really have a personal identity anymore. It was like we were Living Skin. Now it feels like a reset, like I’m re-entering a normal system of life. I think it’s gonna be that way, at least. But I’m also really hoping for a part of what I had with Jerome being possible between the four of us in the new space.

CSW: I’m curious about this phrase you used, the “normal system of life.” Are you more comfortable with a system of your own creation?

AK: I’m glad you brought this up, because I’m realizing now that by me saying that, it is a sort of a refusal to believe that this has been any sort of normal way of living. I think it’s one of the reasons why we had this looming passion in us for years—we felt caught in the waves of a system we didn’t really choose. Having a stable, strictly-houred job, coming home to an apartment with a kitchen, a real window, a real bedroom, blah blah blah. Yes, it is normal, but having a chance to say no to that, and make our own one, was the thing for us at the time. But I don’t know if there is a way to go back to it after all this.

CSW: Will the process be different, working with three new people instead of Jerome?

AK: I think it’s special to go into it with four people together, to have more of a curatorial partnership. There’s a lot of liberty with that, knowing the burden is split between four and not two. I feel like that allows me to take more risks. Jerome will still be a part of it as much as he can.

CSW: So it’s relieving to be moving then, in a way.

AK: It’s a back and forth. About six weeks ago, I pretty much decided I’m never coming back to Wyckoff. Definitely not to this street for a while, just to cleanse. But I know I'll miss it a lot. The new space has some sound limitations, and we’ve hosted some great parties and DJ nights, which I’ll miss a lot. That’s a trademark Living Skin thing that will be gone. But I’m going to be very happy about not hearing the smoke shop down the street blasting music every night. That I won’t miss.

You have to work hard, you have to care less, you have to fight against following the current feel of contemporary art. Our exhibitions were made primarily to unite people and break barriers, but we know those reserves are dwindling. That all starts with how you speak, how you live and treat yourself, and your world views. Doing honest, stupid shit you feel needs to be done, that needs to win.

Finding the spin we can take, the innovation we can make is gonna be super interesting to explore. We’re not trying to launch a new brand or identity—to me, that’s not the point. It’s actualizing and proving that different systems can exist.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Living Skin’s new location is at 9 Monroe St.