A Car Driving Itself: In Conversation With the Directors of Pop Gun

A few weeks ago, I rode my orange Dahon folding bike from Sunnyside to South Slope, a good hour in the beating sun, to the apartment where the project space Pop Gun is currently headquartered. Pop Gun resides on a street sandwiched between a power grid and a cemetery. At the door, I was met by the space’s directors Gunner Dongieux and Karla Zurita, who handed me a cup of coffee, and before a full introduction, dove straight into discussing the work installed for their current show, Fantasy Prize. Through the window, the power grid was even more visible, its industrial scaffolding foregrounding a Gothic archway marking the start of Green-Wood Cemetery. Gunner and Karla reflect on the last three years of Pop Gun, through their breakneck speed of programming, anecdotal drama, and the ever-concerning condition of being an emerging artist.

Victoria Reshetnikov: How did you guys meet?

Karla Zurita: We met in Bushwick at this bar called the Secret Pour on a night this fake band called the Soho Boys was performing. This curator I knew decided to introduce us, but the way he did it was ridiculous. He said, “Gunner runs two awesome project spaces, and Karla works at this shitty gallery.” [laughs] And I was like, “Oh my God, wait! There's so much more to me.” So I had to talk to Gunner and explain my whole life story.

Gunner Dongieux: At that point, I had been running Pop Gun for two years.

KZ: I was showing him the large-scale sculptures I make, and coincidentally at that time, Gunner was curating a huge sculpture show. So I couldn’t not advocate for myself then. There’s never this sort of opportunity.

GD: I had this Swiss curator friend approach me with this abandoned building in Gowanus, an old Bat mitzvah joint. She told me they’d give it to us for free for two weeks for a show. And of course I took it—when do we have the chance to show emerging artists at that scale? Karla was in that show and it took off from there. The cute little story that I like to tell is that we’re the best thing that the curator who introduced us has ever curated.

VR: Aw!

KZ: That’s his little line. When I went to my first Pop Gun opening, I remember thinking that Gunner was such a politician; he went up to every single person that walked in and gave them a tour of the space. It was really sweet to see him treat everyone the same way. I remember being very charmed by that.

VR: Gunner, when did you move to New York?

GD: I grew up in New Orleans. I went to Stanford for my undergraduate degree, but before my senior year, COVID hit. I took a gap year and just moved to New York randomly, and was living right next to this mall in Chinatown. I found out they had a space available for 500 bucks a month, so I rented that out and did a show.

I went back to school, finished my degree, and moved back to New York. While I was here, I started showing my own painting practice with other galleries, but Pop Gun was where I was really forming my community.

VR: Can you talk more about your programming model for Pop Gun?

GD: Pop Gun is really a project space, which is a model I was first exposed to in Berlin during my residency at the Berlin Art Institute. In Berlin, if you've proven that you've been in space for two years, the government will just fund you. So there was this culture of concept-forward shows because no one had to necessarily rely on sales. I really wanted to bring that model to New York.

VR: With that conceptual model as your focus, do you ever feel pressure to go commercial?

GD: Especially on the smaller gallery scale, you're definitely pressured into making a program that can sustain itself financially. But because so many of our artists are conceptual, we're always like, how the fuck are we gonna sell this? If I have to fund a show, I'll work two more jobs art handling and pour all the money back into Pop Gun. At the end of the day, I really just want the artist to do the show they want, so I’ll do anything to make that happen.

KZ: Going commercial is, of course, a good way to make money, but it's so restricting—people tell you that you need to send out a press invite two months in advance, to speak a certain way about the work, to walk the walk. There are all these codes you need to follow in order to be successful.

GD: I feel like the only way that’s made it worth it is the way we're doing it right now: limited overhead, just doing the parts we really want to do: the openings, having people over, and building community.

VR: Are there themes or concepts you are each interested in exploring through Pop Gun?

KZ: I'm interested in identity and personal aesthetics. The first show I curated for Pop Gun was Internet Personality Quiz. That group of artists dealt with the internet but weren’t necessarily relying on actual technology in the work. It was about avatar building online and how that affects your real life identity. I followed that thread with the other show I curated Cable Knit, where all the artists worked in this mode of alter ego creation. I end up getting inspired by the artists I show, of course. Cable Knit featured performance artists who’ve turned to installation or sculpture to further their practice, and recently I’ve started moving towards performing in my own work, with my first performance happening at Dia Chelsea in June.

GD: For me, I’ve been interested in fakes and forgeries. I studied computer science at Stanford, which introduced me to ideas of network structures. That background, combined with my experience in the art world, formed this focus on social structures within art worlds and how that influences gallery programming.

Pop Gun not only mirrors our interests in our individual practices, but it is also concerned with the condition of being an emerging artist within New York. We’re always exploring ideas of authenticity and personal identity.

KZ: For emerging artists, there’s this sort of aspiration to be part of a particular group. I'm not so interested in these rigid categories, so for the shows I curate, I like to group artists who otherwise wouldn't exhibit. Not just in terms of aesthetic or concern, but also career level. I think it pushes people outside of their usual ways of working and presenting.

GD: The conceptual, prompt-based shows that we've done definitely push people outside of their comfort zone. In our recent show Miniotics, we asked artists to make a minion, but of course people didn’t want to do that, because it didn’t fit into their practice. With a more prompt-based show, you're asking someone to participate in making in a way they’re not usually doing. It's a different way of working, but at its best, it reveals something about the way we produce, and what creative output can look like.

KZ: It's about flexibility and versatility, and it also relates to the idea of a more commercial practice, where the artist is always under the pressure of making a “body of work,” the same thing every time. The idea of being “defined.” Pop Gun gives artists a break from that. And some artists get really creative about it and figure out a way to use the empty vessel of a minion to fit their practice.

GD: Andrew Straub’s a great example of that. He bought us 10,000 fake followers for our Instagram page. Those were his “minions.”

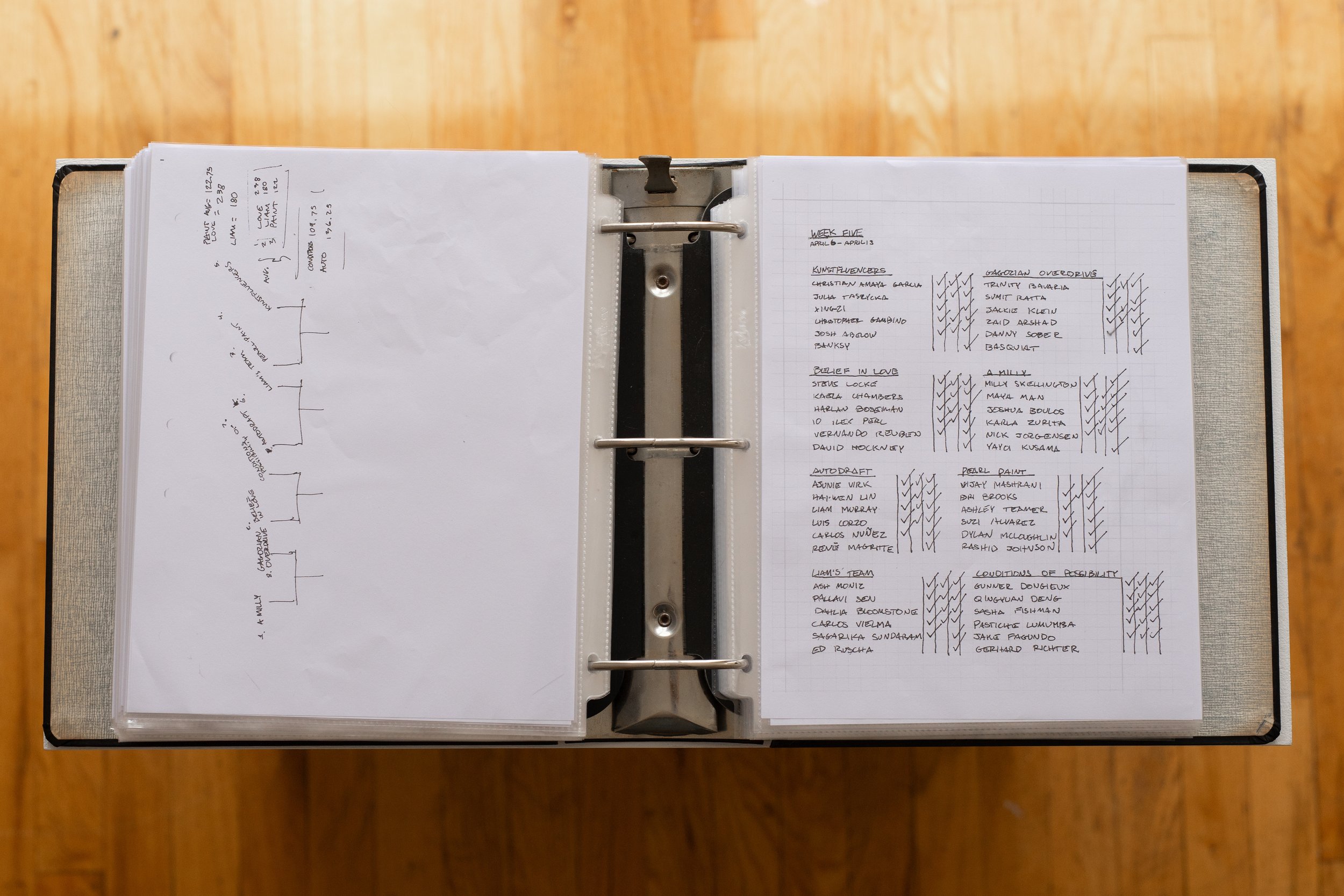

KZ: Or with our current show Fantasy Prize, the artist Liam Murray had a bunch of artists participate in a kind of Fantasy Football League for artists, where they earned points through different “successful” art world things, like solo shows or residencies, for example. That project is called Artist Fantasy League. But a lot of artists didn't want to tell someone their success metrics; it was too stressful to be held accountable in that way. So it also pushed people outside of their comfort zones, really stripping bare our positioning as artists in this weird capitalist landscape we’re living in.

VR: In that way, Pop Gun operates as a collective, because you're not just pushing your own curatorial project forward, you're also pushing the artists you work with forward in the process.

GD: We have parallels to something like an extended friend group for sure; the relationship between us and the artists we work with is very collaborative. The conversations are usually grounded in this condition of being emerging, the anxieties of career success. I don't think the art world is necessarily competitive in the way that we're against each other. At the same time, there are no clear objectives for an art practice. So we're all sort of united and it's just like “banana,” bumbling kind of thing. We're trying to steal the moon but have no charted path to do that.

VR: Where are you guys now, and what are you guys thinking for the future of Pop Gun?

KZ: Fantasy Prize is going to be the last show at this apartment for a little bit. We're going to make another issue of The 60s zine that we made. There's a show in London, a project in Austria. And Miniotics is coming to New York!

GD: We both definitely want to focus more on our individual practices too. At the risk of contradicting myself, I'm saying that we're slowing down for a bit, knowing fullheartedly that there's always going to be another thing that pops up. At this point, Pop Gun has become a kind of autonomous vehicle that’s just driving itself.

VR: It’s a good place to be, though, in the backseat. I wouldn’t get out of the car.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.