Questions on the Canon

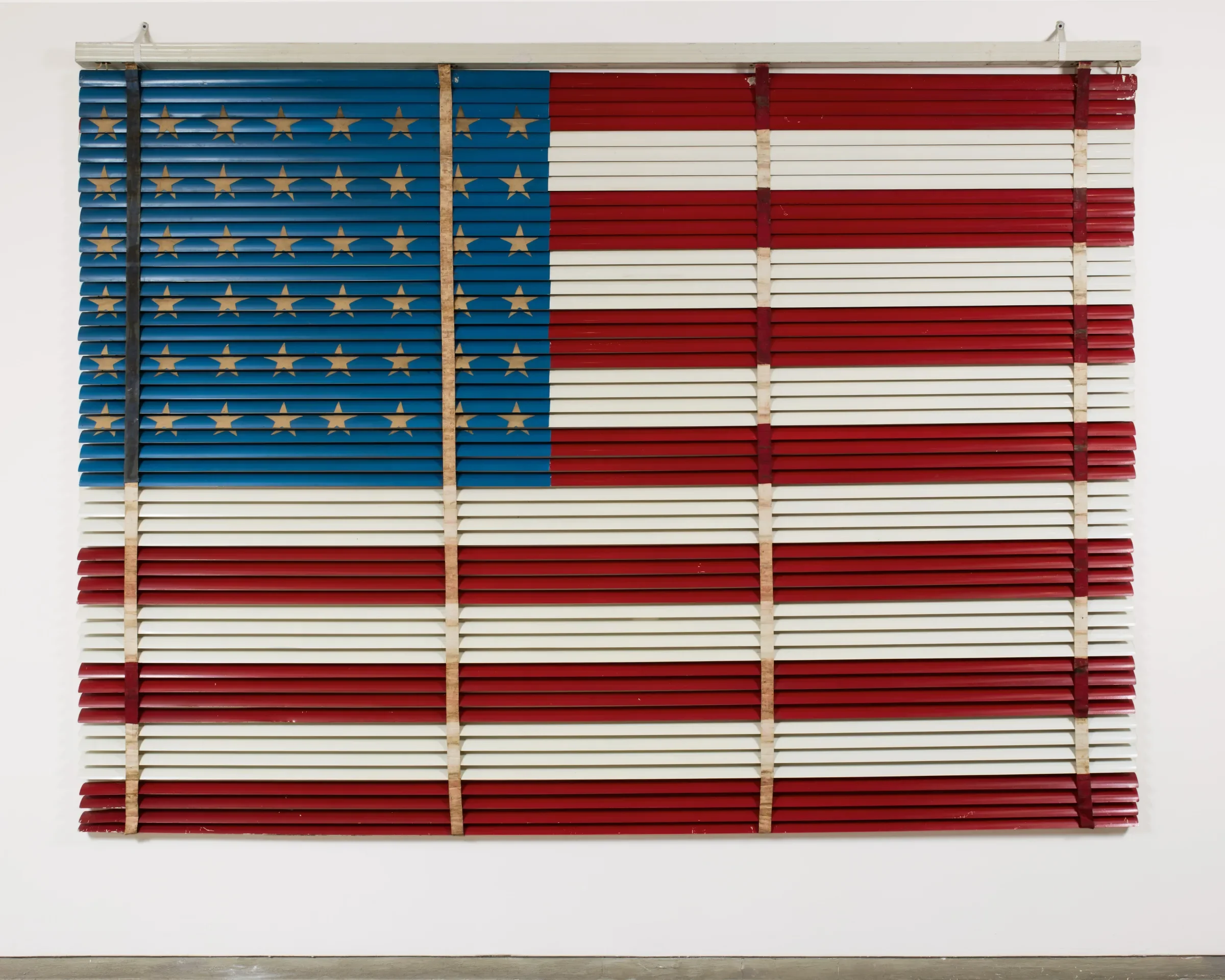

If you’ve ever visited the Brimfield Antique Show, or really any other flea market, the oddities shown in American Vernacular: Art and Objects by Unknown Artists, both on view at Ricco/Maresca and online, might feel familiar. Bringing together works of varying forms and functions, this eclectic collection is emblematic of the gallery’s focus on outsider, self-taught, and folk art. Some works are quaint, like the hand-painted Mystery Game Box with Rotating Card Suits (ca. 1930–40); others, such as the Rhode Island Hospital Architect’s Model (1863), display utilitarian charm. Among carved bucolic figures sit a few brash displays of iconography in the characters of Superman or Mickey Mouse.

The question of the canon is a generally steady undercurrent in discussions of art history, but for obvious reasons, it rises to the surface when considering works like these. It seems almost a necessity that a show of works by unknown or under-recognized artists poses a series of questions, the first of which is: are these artists truly unknown, or are their names just not known yet? The precedent of the canon is one of ritual overlooking and omitting. Marginalization and subjugation in life do not beget posthumous fame and profit, but to what end and for whom?

“Outsider”, “self-taught”, “folk”—the language ascribed to these genres can feel pejorative. If works are crude or stylized, the underpinning assumption is often that the artist lacked sufficient skill or expertise. But at their core, the descriptors the art world has decided upon speak less to the art itself and more to the works’ relationship to the market. Why are the objects here different from those shown at MoMA or the Whitney? What differentiates these works by self-taught artists from the works of self-taught artists such as Frida Kahlo or Vincent van Gogh?

One possible answer suggested by the gallery is intention: the idea that these objects were not created spontaneously and independently from the whims and fancies of the market. This, then, begs the question, why have these objects, never intended for public consumption—both in those with a functional purpose and those purely aesthetic—become valued at this scale, while other similar items sell for a fraction of the price at your local flea?

In a flea market, beauty may be in the eye of the beholder, but in Chelsea, value is in the hand of the gallerist. The question of value sits at the crux of the art world. In considering this, it would be remiss not to look to Pierre Bourdieu and his ever-prescient Distinction for guidance.[1] The complex currents of class and hierarchy no doubt shape the environment and milieu in which these items exist, but I will spare you a treatise on cultural capital. To the best of my understanding, in its distillation, the je ne sais quoi at the heart of value is narrative.

When objects gain significance in this way, it is often for something they can tell us in retrospect. In some instances, this narrative forms around the identity of the maker. I think of David Drake, also known as Dave the Potter, who spent the majority of his life enslaved, whose ceramics and poetry preserve the acts of defiance taken by their artist in their creation. But with many of the artists in American Vernacular still unidentified, that is not the case. Instead, we are left with visual cues on culture and the functions of creative objects of the past. What do these objects tell us about the time in which they were made and the role creativity played in their making? The last narrative is one told through the curatorial choices made by Ricco/Maresca. Why these objects? Why bring them together? And why now?

American Vernacular: Art and Objects by Unknown Artists is on view in person and online at Ricco/Maresca from June 12 through September 13, 2025.

[1] Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, trans. Richard Nice (Harvard University Press, 1996).