Metaphorical Births and Exorcisms with Elizabeth Glaessner

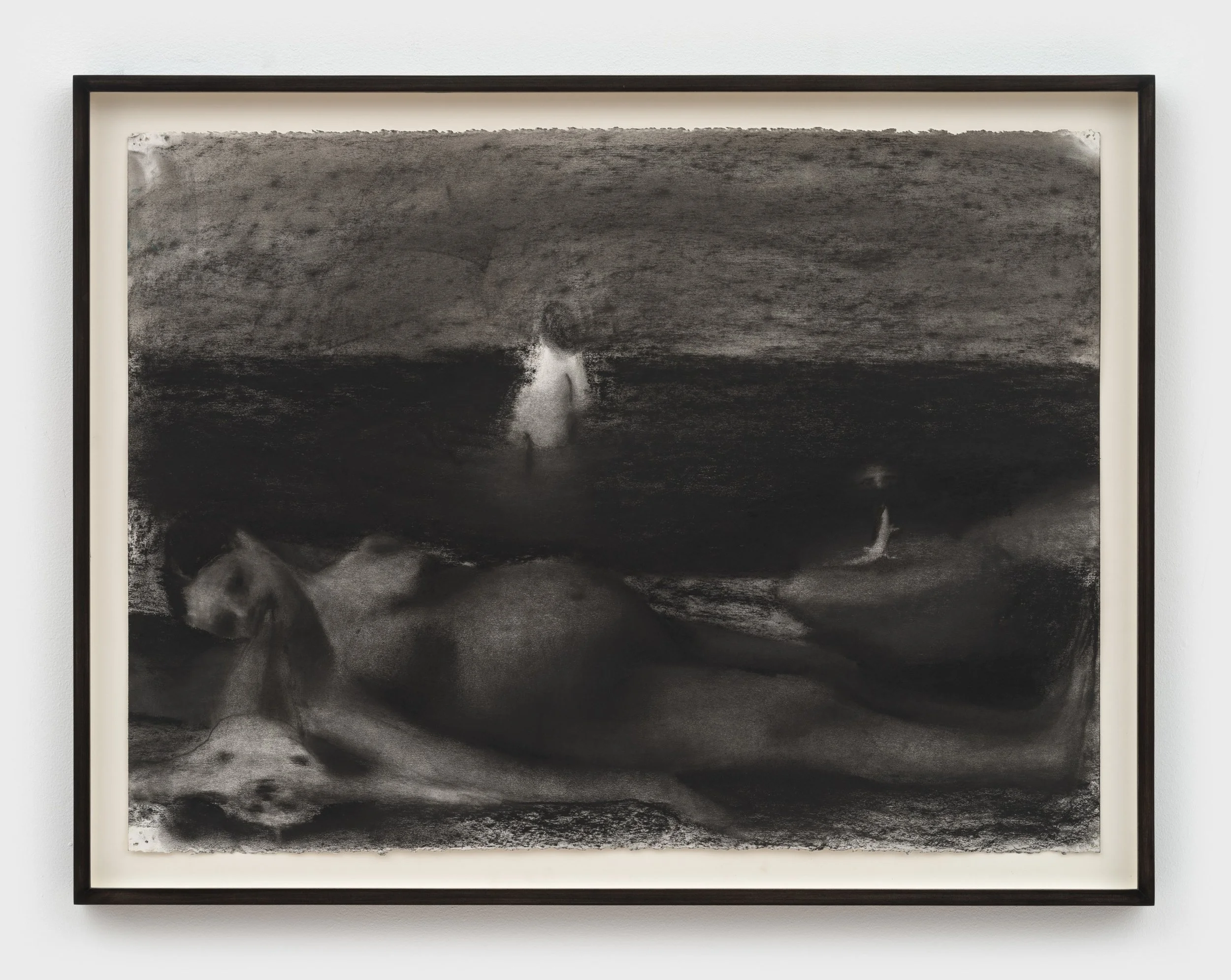

Elizabeth Glaessner explores the body as a pregnant site of enigmatic memories in large-scale paintings that invite complete immersion. Inspired by the work of Symbolists, Glaessner returns to the painting process to form the building blocks that shape, transform, and construct new meanings. For her fourth solo show at P·P·O·W, Running Water, Glaessner started with black-and-white charcoal studies—two of which are on view—to contest boundaries of objecthood, with water serving as metaphor and medium. Equipped with Julia Kristeva’s concept of abjection and posthuman phenomenology, her newest body of work thrums with a tension at the poles of suppression and catharsis. Ahead of the opening, I stopped by Glaessner’s Brooklyn studio to talk about the creativity of psychoanalysis, Haruki Murakami’s running routine, and the fleshiness of oil paint.

Lily Kwak: How are you feeling about your show?

Elizabeth Glaessner: Talking about painting can be tricky because so many of my ideas are wrapped up in the paint and are mysterious to me. It’s been an intense year, and I think that has seeped into the paintings. I’ve been working on the paintings in the show for about a year. I started with charcoal drawings, which is different—I usually start with watercolors or small paintings. I think that starting from black and white—stripping color away—was helpful to figure out the ideas.

LK: I’m excited that your studies made it into the show. Which ones on view started with the charcoal?

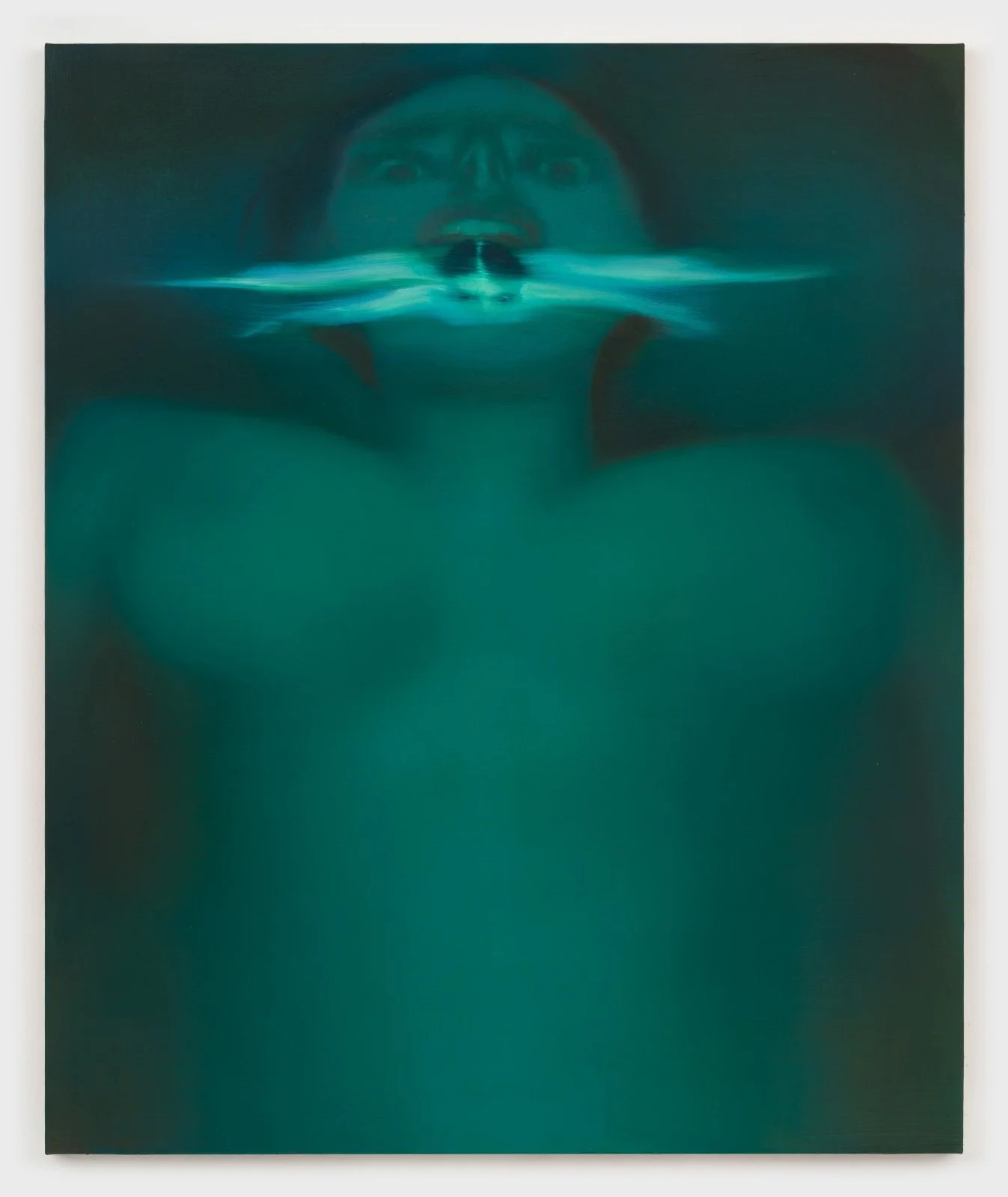

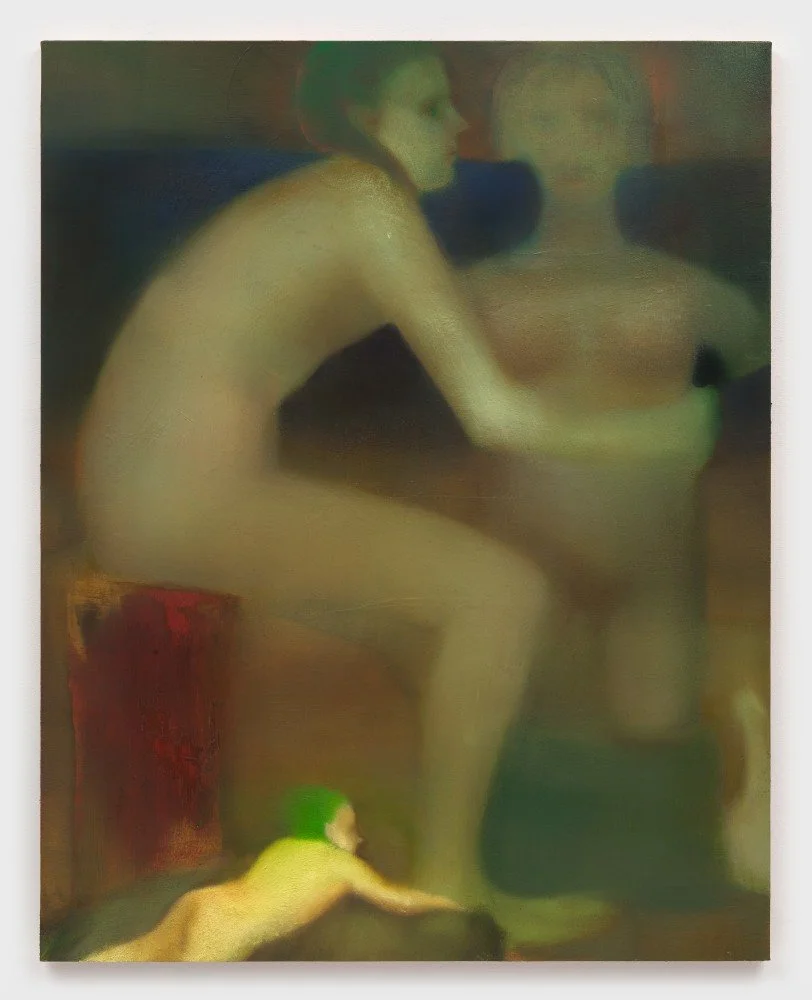

EG: The first one I did has this spirit coming out of a mouth. I was thinking about different forms of metaphorical birth and of exorcisms, this sort of cathartic release, maybe the self being birthed from itself. Then Out of Body (2025) has a pregnant figure, in the sense of being pregnant with ideas that aren’t ready to come out. I was feeling that way at the beginning of the year—ideas gestating but not coming out. That state is sort of cyclical in painting. In the drawing, the pregnant figure is also starting to purge another figure through her mouth, which changed once I started making the painting. I also lost the guy’s head, which confronts the lizard. I started the painting with some transparent, washy layers of warmer tones—I knew that I wanted this gritty, warm earth next to a really cold body of water.

LK: I love the temperature and tone in that one.

EG: I was looking at Caspar David Friedrich’s The Monk by the Sea (1808–1810). There’s a dark, heavy mist that separates the water from the sky yet also unifies them, and the shadowy sand is painted so minimally, but remains so tangible. The title of the show is Running Water, and one of the things I’ve been thinking about is the body as a leaky, porous vessel. I’m reading Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology by Astrida Gundega Neimanis, which posits that the body is inextricably linked to hydrological systems. What we eat or consume is from, at some point, a body of water, and then it cycles through us and ends up back into those water sources.

It also made me think of a myth in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, where Arethusa, a nymph, turns into a spring to escape Alpheus, a river god. Here, water becomes a source of safety. But as we’re experiencing more drought, floods, and contamination of our water systems, I’ve been thinking about how bodies are implicated and how that safety is compromised.

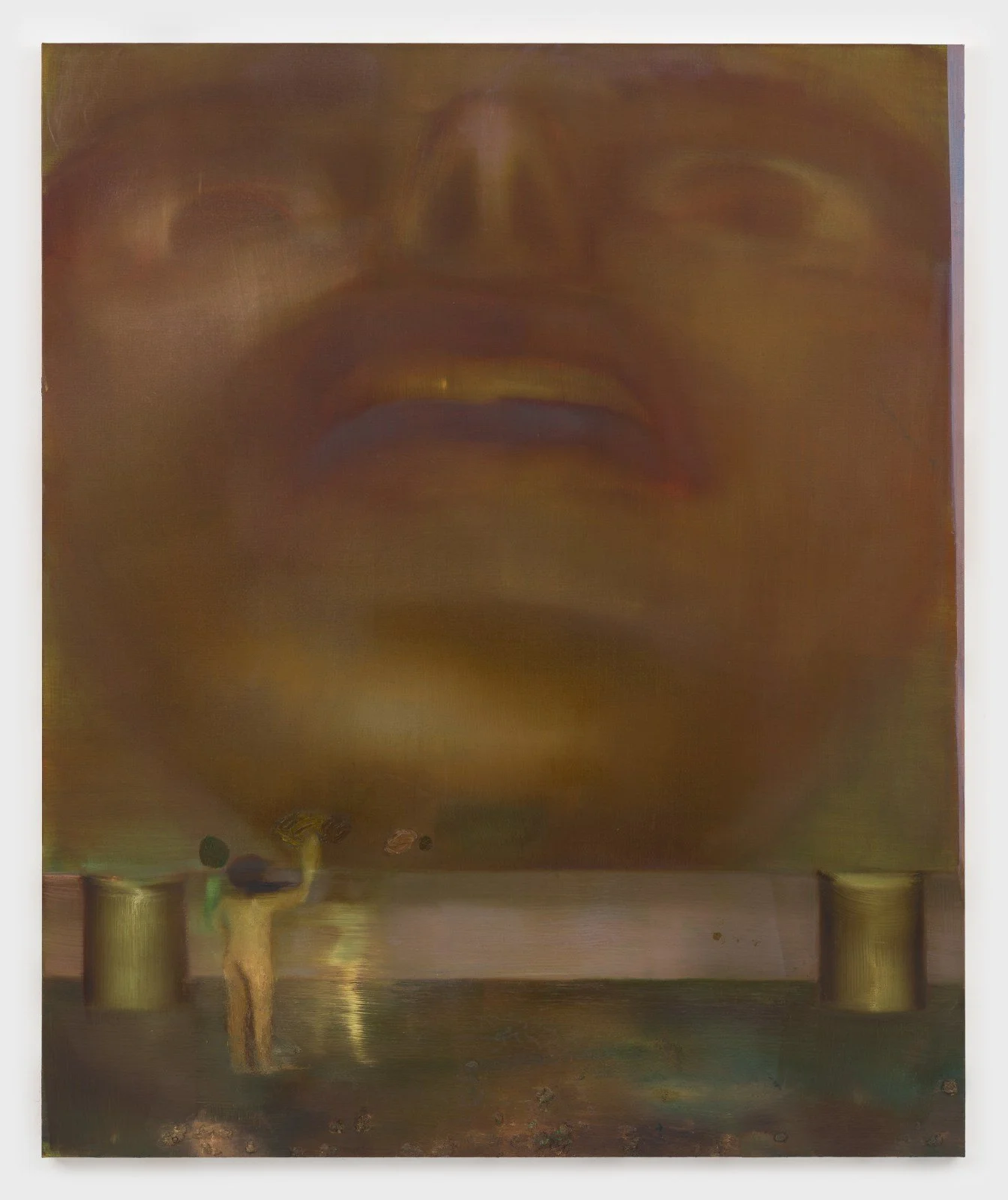

LK: When I was looking at Big Head (2025), I was reminded of Julia Kristeva’s notion of abjection. The figures at the bottom of the painting also remind me of doppelgängers and doubles in relation to Freud’s definition of the uncanny: an unsettling or frightening feeling arising from something familiar that can’t be quite placed, deriving from a repression.

EG: Yeah, I have a quote here from Kristeva: “It is not a lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, order . . . I expel myself, I spit myself out. I become, I give birth to me in the violence.”[1] The mouth as a site of rupture and the body’s boundaries as zones of tension are never secure.

In painting, I interrupt the borders so that the edges leak out, and the environment leaks in. I was also thinking about that painting as coming after Holy Fury (2025). The small figure leaving the mouth, or being breathed out, becomes the little painter painting the head that it left. You also see that shadow figure, which is maybe a continuation of the cycle—it’ll end up going back into the mouth, and then the cycle repeats.

LK: What’s your relationship with psychoanalysis?

EG: People have asked me, like, “Oh, are the paintings about your dreams?” They’re never an illustration of my dreams, but I do dream analysis. If I get stuck with the language to describe something, I’ll do a quick drawing and use it as a starting point for conversation. Some of the drawings for the show started this way, like Holy Fury. Doing analysis has been helpful for me to figure out how certain forms start to gain some meaning or significance to me. It creates a logic for me to use in a painting in a different way. In Labor (2025) references art making, but it’s also a metaphor for analysis. There’s a catharsis in the material artmaking process: for example, the sense of release when clay is purged and is then used to create a new form. So a blob of paint is both physical and metaphorical material.

My analyst has an interesting perspective—our conversations are creative and tangential, almost like improv. I’ve done other types of therapy, but when I started psychoanalysis, there was so much that I never said out loud because I had this idea that that suppression was helping me make work. I got a bit superstitious about it, so it felt good to demystify that. It can also be pretty intense, though. Even some of the works on view are a little hard to look at because they stem from things in my childhood that came out through psychoanalysis. But then, through painting, I can bend the meaning.

LK: When did you start making work at your current scale?

EG: I think in undergrad, when there was a lot of space. It’s a completely different experience working large—it’s more physical and immersive. I’m covered in paint, and I have to get into weird positions to reach certain parts of the canvas. Sometimes, that contortion comes out in the painting, whereas painting small can be more cerebral.

LK: Do you have any routines for working? Is there a sacredness to the state in which you work?

EG: I ran track in college, and then at a certain point, I was like, “Well, I don’t want to wake up at four in the morning anymore,” so I quit running competitively but continued it as a form of exercise or meditation. That discipline and routine has helped me in art making, and I followed Haruki Murakami’s memoir, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, for a very long time. It’s also a good time to let my mind wander. In these last few years, I got out of the routine, and I’m starting to miss it. In the studio, I’m pretty amorphous, and it’s important to me now that nothing feels too sacred.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Elizabeth Glaessner: Running Water is on view at P·P·O·W from September 5 through October 18, 2025.

[1] Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (Columbia University Press, 1982), 4.