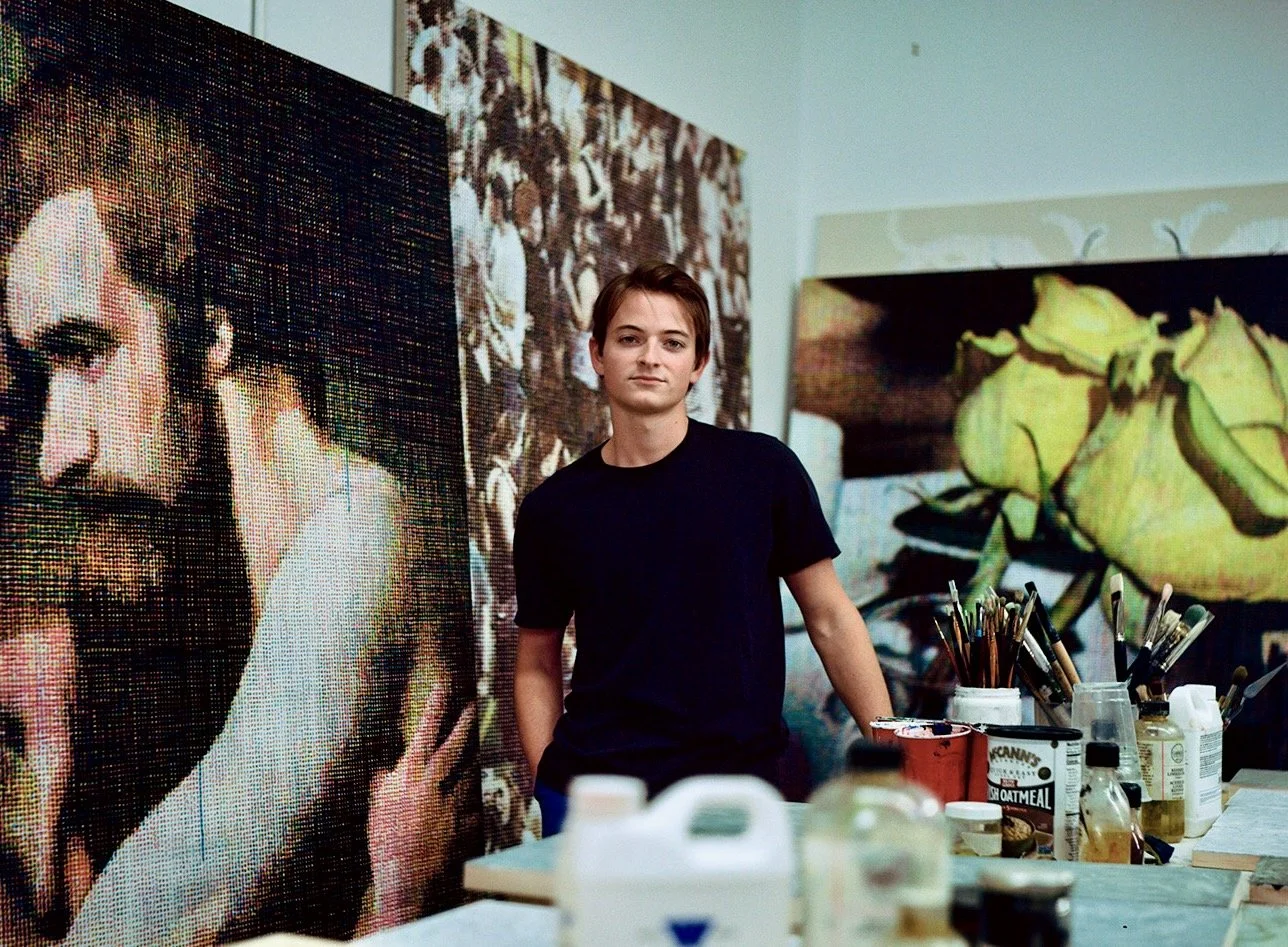

Image, Object, and Compression with Asher Liftin

Employing an “algorithmic” approach to image-making, Asher Liftin (b. 1998) explores the interplay between objects and the visual perception thereof. Informed by a background in cognitive science, the artist uses grids and matrices in the context of image reproduction. In an interview with artist and writer Parker Ewen, Liftin unpacks how his work manipulates object-image relationships and inhibits the viewer’s direct access to a world of optical illusions.

PE: Congratulations on your piece in Rachel Uffner’s Arcus. It’s really a great show. Jumping right in, was your piece specifically made for the show?

AL: Yes, it was made specifically for the show. With the arc theme, I opted for a formal direction in terms of motion. A lot of the images that I choose to paint are things that I can use to compress the relationship between image and object. For example, in this painting, the windshield wiper that's wiping away the paint on the surface has a playful relationship to that compression. It’s instantiating the image as a painted thing in space. It's also playful in that it becomes this wiping away of the actual dot matrix that the image is built out of. Car imagery, like highways, has always been in my work, and so that was a natural way of iterating on the theme.

PE: I was going to ask about your imagery and how you choose what you render. So, you're thinking a lot of compressing, you said, “image and object.”

AL: A lot of the images that are in my paintings are moving: they are translated from something I see into a photograph, and then they are put into a digital space and become a representation of information rather than a picture. In the painting process, rendering the image by hand brings the information back into a physical space and gives it material properties and physicality.

For me, it's completing that loop that is important. For the painting Wipe especially, that change from information to a handmade thing becomes exaggerated by the fact that you have this playful but illusionistic gesture made by the windshield wiper within the image rather than the artist’s hand. The removal of paint on the canvas’ surface is in the plan for the painting itself, rather than expressed by the actual removal of the paint after its application. Jasper Johns has these paintings with actual wipers on them. I think that that must have been in the back of my mind somewhere.

PE: In your other piece Marks on a Grid, there’s a window frame that becomes the removal of the painted surface. It seems like a continued exploration within your works.

AL: Totally. In that painting, you have the bars of the window becoming the framing device but also a grid. In my paintings of windows, the interest is in the way that the dot matrix of the paint itself forms from a system of finer grid that then is mirrored in the architecture of the building, which becomes the architecture of the canvas, too. It allows me to play with surfaces and equate imagery with object.

PE: When I first looked at your work, what came to mind was the digitalness of this pixel system you use. But at the same time, it could also be read as weavings and tapestry. Could you expand on the relationship between the handicraft of your work versus the digitalness of it?

AL: Because it's operating on layers of transparent grids that are superimposed, when you're seeing it from a distance, you really read this kind of tapestry-like surface. That’s interesting to me for a couple of reasons. First, it was not intentional. It was a result rather than something I sought after. Second, the technology behind the loom—the very, very analog programs that would dictate the fabric weavings—provided the building blocks of the first computers and the logic systems. So the Jacquard loom is basically the predecessor for the computer. I think it's because of their similar DNA that the textile visuals come back once the digital image is painted.

I like setting up those types of relationships where play sets the object in space. Reminiscent of the game Telephone, the information changes, and as it becomes repeated, the next stage needs to have the record of the previous one. The final stage holds all of it’s past iterations, but now the information is fully materialized into a physical object.

PE: I know you went to school for both art and cognitive science. I was curious about how those two things partnered for you.

AL: At the same time that I was studying art, I was also studying the human visual system. I was interested in the idea of transparency and the networks used to build imagery in the brain. Cognitive science was an introduction to very rigid rules and procedures. You’re basically trying your hardest not to interpret anything in a subjective way.

In bringing this rigid system of thought from cognitive science into painting, I could take this idea of objectivity through iterative structures, but choose when to follow it. The system for reproducing the imagery allows me to take something I’ve seen with my own eyes and then get a lot of distance from it because of the layers of processing that happen. A lot of things happen without me making such active decisions after planning the image. In using this semi-rigid system, you're creating a built-in, artificial looseness where things can drip, things can mutate. So the balance is a bit absurd, but that is, I think, the fun of it.

PE: You said “artificial looseness.” That brings to mind your pieces that include a swirl motif, which gives some looseness to the grid, but you're still following a precise swirl that I'm guessing was digitally imposed.

AL: With those pictures, you have this sense of the image as a static thing, but then you impose a gesture onto it, which almost destroys the information, creating a strong sense of surface. The swirl highlights the canvas’s quality as a flat solid plane rather than a space you can enter into. What interests me about it is that the gesture of the image is not coming from my hand. Because the image is digitally compressed, it can be instantaneously manipulated as a whole matrix rather than like a painting surface which functions very differently. You apply paint one stroke at a time so you can't do something all-encompassing such as blur it or stretch it. You can't do things that require editing the entire surface in one instantaneous movement. The composition is not organized by hand, which is exciting to me. It also creates even more distance between viewers and the original image.

People have a very established sense of what a still life is: it's usually an artist painting what they are looking at, typically on a one-to-one scale. It’s emblematic of the immediacy between the subject and the viewer. The artist is traditionally rendering something and trying to capture its essence and create a physical object that becomes a substitute for the object in itself, whereas my paintings are trying to do the opposite, by eliminating the notion of being able to access the subject. It's through that distance that my paintings get away from that established idea of still life and become more alien.

PE: What is exciting you in the studio right now?

AL: Right now, I’m exploring the gesture as an icon of immediacy in painting. For example, in the case of my last show, I made acrylic gestural abstract paintings and then photographed them and painted them with ink grids over the abstraction. It kind of kills all the associations with abstract expressionism. But, buried inside is a gestural painting that you can’t access because of the reproduced painted image built on top of it.

I’m interested in mechanisms that get in the way of direct experience. Technology is an effective tool for mediation and reproduction. Just as a photograph of a painting can’t capture the nourishing feeling of seeing it in person, relaying information can often fail to convey many experiences. I’m figuring out how I can use these types of mechanisms to create objects and paintings that can engender meaningful experiences because of those disruptive mechanisms. For example, I can start with a visual that has little value, and through the process of reproduction, turn it into a worthwhile painting. I think that's much more interesting than starting with a pleasant visual and watching it lose something through reproduction.

This interview is edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Arcus is on view from July 11 to August 16, 2024, at Rachel Uffner Gallery, 170 Suffolk St, New York.

Edited by Xuezhu Jenny Wang